Just before Christmas, I was doing some last-minute shopping in one of the Oxford Street department stores. As usual at that time of year, there was a long queue for the checkouts. When I eventually got to a till, I was surprised to see two people there. There was a young man operating the till. And there was a tall older man bagging the goods sold. Although they were busy, you could tell that they were working well together, and enjoying exchanging a few words with customers and each other when they could.

Despite this, the older man had a gravitas that you associate more with the Board room than with the tills of a busy store. Not surprising really – he was a senior manager doing a shift supporting the front-line staff at their busiest time. What was surprising (apart from him being there at all) was the easy way he appeared to be accepted as part of the team.

Here was a real “one-team” culture in action. He was not just doing what the organisation expected. He was doing what he believed in, and so it came naturally. His colleagues saw it as perfectly natural and normal too. Everyone was comfortable, and it worked.

Culture is the pattern of behaviours that people adopt in order to be accepted in a community. It is defined by what people really value, not what they say they value. In that store, people really valued working together as one team to deliver happy customers. That meant that there was nothing awkward about managers working on the tills. Actions speak louder than words, and clearly it works for them.

Just before Christmas, I was doing some last-minute shopping in one of the Oxford Street department stores. As usual at that time of year, there was a long queue for the checkouts. When I eventually got to a till, I was surprised to see two people there. There was a young man operating the till. And there was a tall older man bagging the goods sold. Although they were busy, you could tell that they were working well together, and enjoying exchanging a few words with customers and each other when they could.

Despite this, the older man had a gravitas that you associate more with the Board room than with the tills of a busy store. Not surprising really – he was a senior manager doing a shift supporting the front-line staff at their busiest time. What was surprising (apart from him being there at all) was the easy way he appeared to be accepted as part of the team.

Here was a real “one-team” culture in action. He was not just doing what the organisation expected. He was doing what he believed in, and so it came naturally. His colleagues saw it as perfectly natural and normal too. Everyone was comfortable, and it worked.

Culture is the pattern of behaviours that people adopt in order to be accepted in a community. It is defined by what people really value, not what they say they value. In that store, people really valued working together as one team to deliver happy customers. That meant that there was nothing awkward about managers working on the tills. Actions speak louder than words, and clearly it works for them.

Walking the Talk

That experience prompted me to re-read Carolyn Taylor’s “Walking the Talk”, an excellent introduction to corporate culture. Here was an organisation that has a clearly-defined culture, and knows how to maintain it by walking the talk. Sadly, in my experience most leaders are better at the talking than the walking, and in any case most organisations don’t really know what culture they want (if they think about it at all). That’s a lot of value to be losing. I’ve just come back from the local parcel office with a parcel. Yesterday I had one of those cards through the letterbox that tell you that they had tried to deliver a parcel, and I could collect it from the office.

The thing is, I know that they didn’t try to deliver the parcel. I was in, and the card just came through the letterbox with the other mail. I was next to the front door at the time - no ring, no knock.

Of course I understand that a large proportion of people they have parcels for are out when they call. I can see that they are just trying to make the jobs of the delivery people more efficient. It saves them the effort of carrying all that extra weight and bringing most of it back again. It saves them waiting to see if someone answers. And it saves them having to write out cards on the doorstep, possibly with rain smudging the ink and making the card go soggy.

The thing is though, I have paid to have that parcel delivered. I knew that I was most probably going to be in when the mail came round, so I was happy to take the small risk that I wouldn’t be and that I would have to collect it. I paid them to take the risk that I wouldn’t be in, with its efficiency implications. By writing out the cards without the parcel even leaving the office, they avoided the risk I have paid them to take, and transferred the inefficiency to me. Sadly, it is not just one organisation doing this – I have had similar experiences with other delivery services.

I’ve just come back from the local parcel office with a parcel. Yesterday I had one of those cards through the letterbox that tell you that they had tried to deliver a parcel, and I could collect it from the office.

The thing is, I know that they didn’t try to deliver the parcel. I was in, and the card just came through the letterbox with the other mail. I was next to the front door at the time - no ring, no knock.

Of course I understand that a large proportion of people they have parcels for are out when they call. I can see that they are just trying to make the jobs of the delivery people more efficient. It saves them the effort of carrying all that extra weight and bringing most of it back again. It saves them waiting to see if someone answers. And it saves them having to write out cards on the doorstep, possibly with rain smudging the ink and making the card go soggy.

The thing is though, I have paid to have that parcel delivered. I knew that I was most probably going to be in when the mail came round, so I was happy to take the small risk that I wouldn’t be and that I would have to collect it. I paid them to take the risk that I wouldn’t be in, with its efficiency implications. By writing out the cards without the parcel even leaving the office, they avoided the risk I have paid them to take, and transferred the inefficiency to me. Sadly, it is not just one organisation doing this – I have had similar experiences with other delivery services.

Keep your promises

A more honest approach would be to offer two categories of delivery at two different prices: a cheaper service, where you know you will have to collect, and a more expensive one where the attempt to deliver will be made. That way you could price the risk realistically. But providing the cheaper service when the customer has paid for the more expensive one is just wrong. In most industries, you would not get away with it. I have no doubt that they are all under a lot of competitive pressure. Probably local managers have concluded that it is necessary to do this to meet the tough performance targets which result. If so, that betrays both a cavalier approach, and a lack of joined-up thinking. If you don’t give your customers what they pay for, sooner or later they stop being customers. As a professional change manager and consultant, I get asked to advise on how to bring about cultural change in organisations. Often, part of the conversation goes something like this:

“We really need to change how we do things. We just don’t have enough hours in the day to get everything done.”

“Yes, I can see that that would be a problem. I’m sure that there is a better way. It sounds like you need to delegate more. How comfortable are you with delegating to your managers?”

“That would be fine. But the problem is, our staff don’t have enough time for everything they need to do now either.”

“Hmm. You need a change programme – which you will need time and energy to lead – but you don’t have any spare capacity, and there is nowhere you can delegate stuff to free up some. So what parts of what you do now are you willing to see not being done at all to make the change happen?”

That often produces blank looks. But you have to devote time to leading change if you want it to succeed. You also have to lead by example. You have to demonstrate that change is a sufficiently high priority for you that it displaces other things. Other people are unlikely to change what they do until they see you changing what you spend time on, not just talking about doing so.

As a professional change manager and consultant, I get asked to advise on how to bring about cultural change in organisations. Often, part of the conversation goes something like this:

“We really need to change how we do things. We just don’t have enough hours in the day to get everything done.”

“Yes, I can see that that would be a problem. I’m sure that there is a better way. It sounds like you need to delegate more. How comfortable are you with delegating to your managers?”

“That would be fine. But the problem is, our staff don’t have enough time for everything they need to do now either.”

“Hmm. You need a change programme – which you will need time and energy to lead – but you don’t have any spare capacity, and there is nowhere you can delegate stuff to free up some. So what parts of what you do now are you willing to see not being done at all to make the change happen?”

That often produces blank looks. But you have to devote time to leading change if you want it to succeed. You also have to lead by example. You have to demonstrate that change is a sufficiently high priority for you that it displaces other things. Other people are unlikely to change what they do until they see you changing what you spend time on, not just talking about doing so.

Change needs time

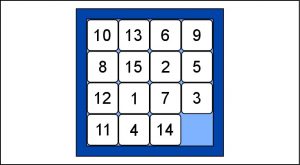

Think of it like a sliding-tile puzzle. In a 4 x 4 puzzle there are 15 tiles, so that there is always one space to move the next tile into. That gives enough flexibility to rearrange all the tiles into the right pattern. If there were 16 tiles – completely filling the frame – nothing could move at all. You have to find an empty space in your time, like the missing tile, to be able to rearrange your organisational tiles. Like many things in life, this is just about priorities. If change is high enough up your priority list, it will displace other activities to create the necessary space. If it isn’t, it is best not to start. This seasonal message will help you to remember!

It was only in the latter stages of the referendum campaign that the penny dropped for me. I realised that the reason that the campaign was so much about emotion and so little about facts and likely consequences was that, whatever its ostensible purpose, the referendum had come to be about who we are. My identity is what I believe it to be, and what those I identify with believe it to be. The outcome of a referendum does not, cannot, change that, even if it can lead to a change of status.

It would obviously be nonsense if, when you asked someone whether they would be best off staying married or getting divorced, they stated their gender as the answer. Politicians have allowed a question about relationship to be given an answer about identity. Apples and oranges. In so doing they have shot themselves – and at the same time the whole country – in the foot.

How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

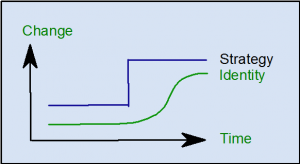

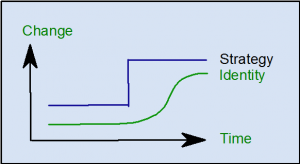

Identity and change

There is a profound lesson about change there. Identity is perhaps the ‘stickiest’ phenomenon in culture, because belonging is so fundamental to our sense of security. A change project is often perceived as changing in some way the identity of that to which we belong. However, peoples’ sense of identity changes much more slowly than the strategy. If we do not take steps to bridge the identity gap while people catch up, it is the relationship which is in for trouble. How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

I once worked for a young organisation with big ambitions. The managers were all highly experienced, but had only recently come together as a team. They decided to contract with a long-established and very stable international firm to help with operations.

I don’t think anybody was expecting what happened next. The partner firm arrived, and immediately started to call the shots. Needless to say, hackles rose amongst my colleagues – we were the customer, after all: isn’t the customer always right? It took some considerable (and uncomfortable) time to make the relationships work.

What happened? This was all about organisational maturity. The partner organisation had well-established ways of doing things and strong internal relationships. Everyone knew what they were there to do, and how it related to everyone else. They knew that their colleagues could be trusted to do what they expected, and to back them up when necessary. That organisational maturity gave them a high degree of confidence.

My organisation, on the other hand, had none of that. Although individuals (as individuals) were highly competent and confident, there had not been time for strong relationships to develop between us. Although there would be an expectation of support from others, without having been there before certainty about its strength, timeliness and content was lacking. In those circumstances, collective confidence cannot be high. Eventually our differences were sorted out, but it might have been quicker and easier if the relative lack of organisational maturity and its consequences had been recognised at the start.

Confidence comes not just from the confidence of individuals. It is also about the strength of teamwork, and a team has to work together for some time to develop that trust and mutual confidence. When two organisations interact, expect their relative maturities to affect the outcome.

Review of 11 Rules for Creating Value in the Social Era by Nilofer Merchant

Perhaps surprisingly, given the title, Nilofer Merchant’s short book is not so much about the ‘how’ of social media, as the paradigm shift it has enabled in the way that most of the world does business.

In the old days, ‘efficiency’ – doing things right – ruled. You made more money by having more efficient processes, and by having the scale to cover your high fixed costs easily. Large dominant players with efficient processes made it almost impossible for small companies to overcome the barriers to entry. In the past those approaches may also have been ‘effective’ – doing the right things – but the context has changed.

In the new world, while scale and efficiency can be good strategies where there are low levels of innovation and change, the inherently cautious response of big, efficient organisations becomes a disadvantage: the ‘right things’ change too fast. High rates of innovation and change have become possible through the power of social media. Merchant says that a new approach is needed, based on embracing what social media enables, characterised by

Perhaps surprisingly, given the title, Nilofer Merchant’s short book is not so much about the ‘how’ of social media, as the paradigm shift it has enabled in the way that most of the world does business.

In the old days, ‘efficiency’ – doing things right – ruled. You made more money by having more efficient processes, and by having the scale to cover your high fixed costs easily. Large dominant players with efficient processes made it almost impossible for small companies to overcome the barriers to entry. In the past those approaches may also have been ‘effective’ – doing the right things – but the context has changed.

In the new world, while scale and efficiency can be good strategies where there are low levels of innovation and change, the inherently cautious response of big, efficient organisations becomes a disadvantage: the ‘right things’ change too fast. High rates of innovation and change have become possible through the power of social media. Merchant says that a new approach is needed, based on embracing what social media enables, characterised by

- Community: A far more flexible way of allocating work;

- Creativity: Allowing co-creation of value with customers;

- Connections: A more open approach than in the past to customer relationships.

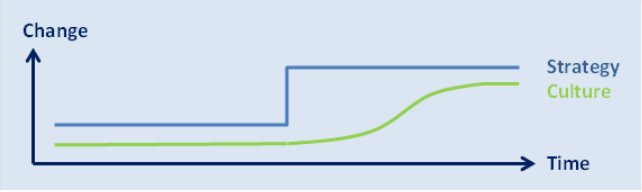

Organisations need two essential frameworks to be able to deliver effectively, both of which must be consistent with the organisation’s vision and mission: strategy and culture. Strategy, describing WHAT they will deliver, and Culture, defining HOW they will deliver it. Usually lots of effort is put into defining the strategy, but culture often just ‘happens’. Nonetheless, success depends on the two working harmoniously together. Take a look at this article for another view of this.

What happens when an organisation faces a disruptive change to its environment? This might be something like an economic or technological change, or, for a major project, might just be moving from promotion to delivery. The first step is usually to update the strategy (and possibly the vision and mission as well) to respond to the change.

So what’s the problem? I think it is that frequently there is no recognition that the change may also require changes to culture to keep it aligned with the strategy. But even if such a change is planned and managed, culture stems from the way people think and behave, and changing it relies on people changing: it cannot be made to change quickly, and certainly not at the same speed as the strategy changes. The disruptive change to strategy then leads to a misalignment between strategy and culture, and this takes time to heal.

Here are two examples where strategy and culture both mattered:

Privatisation

I once worked at a public sector organisation that was privatised. There was a massive (even though long-anticipated) disruptive change in the environment when the transfer happened. Overnight, share price and city reaction to performance became critical, and even though strategy had been becoming more commercial for some while, suddenly it really mattered. Some staff were simply unable to make the cultural shift required for alignment – meaning that until most of those had left or retired, the culture did not become fully commercial. Unfortunately, this process took years – years we did not have.

Major project transition

I also once worked for an organisation set up to plan and build a major infrastructure project. Having for years been focussed on planning and promoting the project, following approval, it suddenly had the challenge of delivering a huge construction project. What had been a fairly small public sector organisation with centralised decision making needed to become an effective delivery organisation in short order. To gain the necessary scale and capability, it let large contracts to firms which were highly experienced in delivering large infrastructure projects. While they brought the energy and focus essential for delivery, it took much longer to bring about an organisational culture that was aligned across staff from all three organisations.

Transition is hard because it requires managing these very different strands in a joined-up way. It needs, on the one hand, the development and implementation of new strategies, requiring vision, analysis, and delivery skills; on the other, bringing about a realignment of culture with minimum delay, requiring people, communication and change skills. And to join them up, it also needs a tolerance for the ambiguity that results while strategy and culture remain out of alignment.

If you are facing a disruptive change, and would like to talk about how to manage the consequences in a joined-up way, contact david@otteryconsulting.co.uk.

Organisations need two essential frameworks to be able to deliver effectively, both of which must be consistent with the organisation’s vision and mission: strategy and culture. Strategy, describing WHAT they will deliver, and Culture, defining HOW they will deliver it. Usually lots of effort is put into defining the strategy, but culture often just ‘happens’. Nonetheless, success depends on the two working harmoniously together. Take a look at this article for another view of this.

What happens when an organisation faces a disruptive change to its environment? This might be something like an economic or technological change, or, for a major project, might just be moving from promotion to delivery. The first step is usually to update the strategy (and possibly the vision and mission as well) to respond to the change.

So what’s the problem? I think it is that frequently there is no recognition that the change may also require changes to culture to keep it aligned with the strategy. But even if such a change is planned and managed, culture stems from the way people think and behave, and changing it relies on people changing: it cannot be made to change quickly, and certainly not at the same speed as the strategy changes. The disruptive change to strategy then leads to a misalignment between strategy and culture, and this takes time to heal.

Here are two examples where strategy and culture both mattered:

Privatisation

I once worked at a public sector organisation that was privatised. There was a massive (even though long-anticipated) disruptive change in the environment when the transfer happened. Overnight, share price and city reaction to performance became critical, and even though strategy had been becoming more commercial for some while, suddenly it really mattered. Some staff were simply unable to make the cultural shift required for alignment – meaning that until most of those had left or retired, the culture did not become fully commercial. Unfortunately, this process took years – years we did not have.

Major project transition

I also once worked for an organisation set up to plan and build a major infrastructure project. Having for years been focussed on planning and promoting the project, following approval, it suddenly had the challenge of delivering a huge construction project. What had been a fairly small public sector organisation with centralised decision making needed to become an effective delivery organisation in short order. To gain the necessary scale and capability, it let large contracts to firms which were highly experienced in delivering large infrastructure projects. While they brought the energy and focus essential for delivery, it took much longer to bring about an organisational culture that was aligned across staff from all three organisations.

Transition is hard because it requires managing these very different strands in a joined-up way. It needs, on the one hand, the development and implementation of new strategies, requiring vision, analysis, and delivery skills; on the other, bringing about a realignment of culture with minimum delay, requiring people, communication and change skills. And to join them up, it also needs a tolerance for the ambiguity that results while strategy and culture remain out of alignment.

If you are facing a disruptive change, and would like to talk about how to manage the consequences in a joined-up way, contact david@otteryconsulting.co.uk.

There you are, head down in a report, a spreadsheet, or some other urgent bit of business. There’s a knock, and your mind returns to your desk from miles away. Someone says they have a problem and can they talk it over with you please? An interruption. What are you going to say?

Your work is high-value, it takes real concentration, and you need to keep your focus to get it done right. On the other hand, if you send them away, you may be telling them that you do not value them and what they do.

Of course my own work seems urgent, but I know I’ll get it done one way or another. My colleague on the other hand is important, because it is essential for the longer term that they feel valued. I could easily – and quickly – damage a relationship I have taken a long time to build. I know they would not interrupt me when I’m busy unless they felt it was important. It is really important to give them something to show that I’m taking them seriously.

Even if I decide I can only spare 5 minutes now, I’ll always offer that as a first step, at least to give them things to be thinking about until I can pay full attention. If I give them proper respect, value them, take their problems seriously, I find that they respect me back – and interruption is rare unless it really is necessary.

So if you really can't deal with the interruption fully there and then, at least find some compromise. It will pay you back in the long run.

There you are, head down in a report, a spreadsheet, or some other urgent bit of business. There’s a knock, and your mind returns to your desk from miles away. Someone says they have a problem and can they talk it over with you please? An interruption. What are you going to say?

Your work is high-value, it takes real concentration, and you need to keep your focus to get it done right. On the other hand, if you send them away, you may be telling them that you do not value them and what they do.

Of course my own work seems urgent, but I know I’ll get it done one way or another. My colleague on the other hand is important, because it is essential for the longer term that they feel valued. I could easily – and quickly – damage a relationship I have taken a long time to build. I know they would not interrupt me when I’m busy unless they felt it was important. It is really important to give them something to show that I’m taking them seriously.

Even if I decide I can only spare 5 minutes now, I’ll always offer that as a first step, at least to give them things to be thinking about until I can pay full attention. If I give them proper respect, value them, take their problems seriously, I find that they respect me back – and interruption is rare unless it really is necessary.

So if you really can't deal with the interruption fully there and then, at least find some compromise. It will pay you back in the long run.