Just before Christmas, I was doing some last-minute shopping in one of the Oxford Street department stores. As usual at that time of year, there was a long queue for the checkouts. When I eventually got to a till, I was surprised to see two people there. There was a young man operating the till. And there was a tall older man bagging the goods sold. Although they were busy, you could tell that they were working well together, and enjoying exchanging a few words with customers and each other when they could.

Despite this, the older man had a gravitas that you associate more with the Board room than with the tills of a busy store. Not surprising really – he was a senior manager doing a shift supporting the front-line staff at their busiest time. What was surprising (apart from him being there at all) was the easy way he appeared to be accepted as part of the team.

Here was a real “one-team” culture in action. He was not just doing what the organisation expected. He was doing what he believed in, and so it came naturally. His colleagues saw it as perfectly natural and normal too. Everyone was comfortable, and it worked.

Culture is the pattern of behaviours that people adopt in order to be accepted in a community. It is defined by what people really value, not what they say they value. In that store, people really valued working together as one team to deliver happy customers. That meant that there was nothing awkward about managers working on the tills. Actions speak louder than words, and clearly it works for them.

Just before Christmas, I was doing some last-minute shopping in one of the Oxford Street department stores. As usual at that time of year, there was a long queue for the checkouts. When I eventually got to a till, I was surprised to see two people there. There was a young man operating the till. And there was a tall older man bagging the goods sold. Although they were busy, you could tell that they were working well together, and enjoying exchanging a few words with customers and each other when they could.

Despite this, the older man had a gravitas that you associate more with the Board room than with the tills of a busy store. Not surprising really – he was a senior manager doing a shift supporting the front-line staff at their busiest time. What was surprising (apart from him being there at all) was the easy way he appeared to be accepted as part of the team.

Here was a real “one-team” culture in action. He was not just doing what the organisation expected. He was doing what he believed in, and so it came naturally. His colleagues saw it as perfectly natural and normal too. Everyone was comfortable, and it worked.

Culture is the pattern of behaviours that people adopt in order to be accepted in a community. It is defined by what people really value, not what they say they value. In that store, people really valued working together as one team to deliver happy customers. That meant that there was nothing awkward about managers working on the tills. Actions speak louder than words, and clearly it works for them.

Walking the Talk

That experience prompted me to re-read Carolyn Taylor’s “Walking the Talk”, an excellent introduction to corporate culture. Here was an organisation that has a clearly-defined culture, and knows how to maintain it by walking the talk. Sadly, in my experience most leaders are better at the talking than the walking, and in any case most organisations don’t really know what culture they want (if they think about it at all). That’s a lot of value to be losing. I’ve just come back from the local parcel office with a parcel. Yesterday I had one of those cards through the letterbox that tell you that they had tried to deliver a parcel, and I could collect it from the office.

The thing is, I know that they didn’t try to deliver the parcel. I was in, and the card just came through the letterbox with the other mail. I was next to the front door at the time - no ring, no knock.

Of course I understand that a large proportion of people they have parcels for are out when they call. I can see that they are just trying to make the jobs of the delivery people more efficient. It saves them the effort of carrying all that extra weight and bringing most of it back again. It saves them waiting to see if someone answers. And it saves them having to write out cards on the doorstep, possibly with rain smudging the ink and making the card go soggy.

The thing is though, I have paid to have that parcel delivered. I knew that I was most probably going to be in when the mail came round, so I was happy to take the small risk that I wouldn’t be and that I would have to collect it. I paid them to take the risk that I wouldn’t be in, with its efficiency implications. By writing out the cards without the parcel even leaving the office, they avoided the risk I have paid them to take, and transferred the inefficiency to me. Sadly, it is not just one organisation doing this – I have had similar experiences with other delivery services.

I’ve just come back from the local parcel office with a parcel. Yesterday I had one of those cards through the letterbox that tell you that they had tried to deliver a parcel, and I could collect it from the office.

The thing is, I know that they didn’t try to deliver the parcel. I was in, and the card just came through the letterbox with the other mail. I was next to the front door at the time - no ring, no knock.

Of course I understand that a large proportion of people they have parcels for are out when they call. I can see that they are just trying to make the jobs of the delivery people more efficient. It saves them the effort of carrying all that extra weight and bringing most of it back again. It saves them waiting to see if someone answers. And it saves them having to write out cards on the doorstep, possibly with rain smudging the ink and making the card go soggy.

The thing is though, I have paid to have that parcel delivered. I knew that I was most probably going to be in when the mail came round, so I was happy to take the small risk that I wouldn’t be and that I would have to collect it. I paid them to take the risk that I wouldn’t be in, with its efficiency implications. By writing out the cards without the parcel even leaving the office, they avoided the risk I have paid them to take, and transferred the inefficiency to me. Sadly, it is not just one organisation doing this – I have had similar experiences with other delivery services.

Keep your promises

A more honest approach would be to offer two categories of delivery at two different prices: a cheaper service, where you know you will have to collect, and a more expensive one where the attempt to deliver will be made. That way you could price the risk realistically. But providing the cheaper service when the customer has paid for the more expensive one is just wrong. In most industries, you would not get away with it. I have no doubt that they are all under a lot of competitive pressure. Probably local managers have concluded that it is necessary to do this to meet the tough performance targets which result. If so, that betrays both a cavalier approach, and a lack of joined-up thinking. If you don’t give your customers what they pay for, sooner or later they stop being customers. As a professional change manager and consultant, I get asked to advise on how to bring about cultural change in organisations. Often, part of the conversation goes something like this:

“We really need to change how we do things. We just don’t have enough hours in the day to get everything done.”

“Yes, I can see that that would be a problem. I’m sure that there is a better way. It sounds like you need to delegate more. How comfortable are you with delegating to your managers?”

“That would be fine. But the problem is, our staff don’t have enough time for everything they need to do now either.”

“Hmm. You need a change programme – which you will need time and energy to lead – but you don’t have any spare capacity, and there is nowhere you can delegate stuff to free up some. So what parts of what you do now are you willing to see not being done at all to make the change happen?”

That often produces blank looks. But you have to devote time to leading change if you want it to succeed. You also have to lead by example. You have to demonstrate that change is a sufficiently high priority for you that it displaces other things. Other people are unlikely to change what they do until they see you changing what you spend time on, not just talking about doing so.

As a professional change manager and consultant, I get asked to advise on how to bring about cultural change in organisations. Often, part of the conversation goes something like this:

“We really need to change how we do things. We just don’t have enough hours in the day to get everything done.”

“Yes, I can see that that would be a problem. I’m sure that there is a better way. It sounds like you need to delegate more. How comfortable are you with delegating to your managers?”

“That would be fine. But the problem is, our staff don’t have enough time for everything they need to do now either.”

“Hmm. You need a change programme – which you will need time and energy to lead – but you don’t have any spare capacity, and there is nowhere you can delegate stuff to free up some. So what parts of what you do now are you willing to see not being done at all to make the change happen?”

That often produces blank looks. But you have to devote time to leading change if you want it to succeed. You also have to lead by example. You have to demonstrate that change is a sufficiently high priority for you that it displaces other things. Other people are unlikely to change what they do until they see you changing what you spend time on, not just talking about doing so.

Change needs time

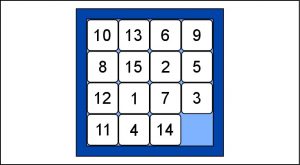

Think of it like a sliding-tile puzzle. In a 4 x 4 puzzle there are 15 tiles, so that there is always one space to move the next tile into. That gives enough flexibility to rearrange all the tiles into the right pattern. If there were 16 tiles – completely filling the frame – nothing could move at all. You have to find an empty space in your time, like the missing tile, to be able to rearrange your organisational tiles. Like many things in life, this is just about priorities. If change is high enough up your priority list, it will displace other activities to create the necessary space. If it isn’t, it is best not to start. This seasonal message will help you to remember! A few days ago I went to a concert. Not a typical one though. I was attracted by the lines “…even if you know nothing at all about…”, and “We know all people will bring intelligent ears with them.” An opportunity to experience something new.

The music was by Karlheinz Stockhausen, a pioneer of electronic music in the 1950s who had a major influence on the world of pop as well as on ‘serious’ music (he is one of the faces on the cover of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper album). It was an extraordinary evening.

Some people might not regard what we heard as music at all, but just a jumble of noises. Beforehand, I might have been one of them. What astonished me was that the whole experience was completely enthralling. The sound as you might hear it from loudspeakers at home was only one element. The virtuosic skill of the performers creating this incredibly complex sound was humbling to watch. The continually-changing spatial arrangement of the sound, and the atmosphere created by being with all those other ‘intelligent ears’ added other dimensions. Somehow, the jumble started to make sense. It was an evening to remember for a long time.

A few days ago I went to a concert. Not a typical one though. I was attracted by the lines “…even if you know nothing at all about…”, and “We know all people will bring intelligent ears with them.” An opportunity to experience something new.

The music was by Karlheinz Stockhausen, a pioneer of electronic music in the 1950s who had a major influence on the world of pop as well as on ‘serious’ music (he is one of the faces on the cover of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper album). It was an extraordinary evening.

Some people might not regard what we heard as music at all, but just a jumble of noises. Beforehand, I might have been one of them. What astonished me was that the whole experience was completely enthralling. The sound as you might hear it from loudspeakers at home was only one element. The virtuosic skill of the performers creating this incredibly complex sound was humbling to watch. The continually-changing spatial arrangement of the sound, and the atmosphere created by being with all those other ‘intelligent ears’ added other dimensions. Somehow, the jumble started to make sense. It was an evening to remember for a long time.

Its worth the risk

If you have never tried something, you can’t know what you are missing. Maybe it won’t work for you. But just as likely you will find new perspectives and insights that you could not have imagined otherwise. It is worth the risk.

In the old days, efficiency (doing things right) ruled. You made money by having more efficient processes than competitors, so your margin was higher on the same price. Scale was rewarded, because it brought efficiency, encouraging huge companies and standardised products. Flexibility was your enemy.

Now, technology has changed everything. Just because it is possible, effectiveness (doing the right thing) will rule. The customer will always be right, whatever they want. Can you imagine people now accepting Henry Ford’s statement that people could have any colour they wanted, so long as it was black? Scale and efficiency is not the only thing that matters any more – in this new world, value comes from responsiveness. Success requires using connections, building a community with customers and suppliers, and being creative.

In the days when efficiency led, market domination was the objective, because that was what allowed you to hold onto your “most efficient producer” badge. In the new world, domination is not the only determinant of success. Your company needs to be like a lumberjack on a log flume – constantly moving to stay on top despite the logs rolling, and needing the agility that comes most easily to small companies to do so.

Use consultants and interims for ideas and flexibility

This model lends itself readily to the de-centralised organisation, using consultants, interims, and other forms of flexible working to provide the skills needed when they are needed. To do this well, the organisation needs to be networked and connected; old-style hierarchies, linear processes and so on inhibit the flexibility required. In this post-Brexit-vote world, where no-one quite knows where we are going or what it will mean, that flexibility to adapt rapidly as the shape of the future emerges will be even more important. Winning will depend on having a culture which embraces flexibility and adapts to change. Darwin had a phrase for it: survival of the fittest. The species that survived were the ones with most variability. Work flexibly; bring in and try out new ideas; find better ways to succeed. Voting to be dinosaurs can’t change the laws of nature.

I once worked for a young organisation with big ambitions. The managers were all highly experienced, but had only recently come together as a team. They decided to contract with a long-established and very stable international firm to help with operations.

I don’t think anybody was expecting what happened next. The partner firm arrived, and immediately started to call the shots. Needless to say, hackles rose amongst my colleagues – we were the customer, after all: isn’t the customer always right? It took some considerable (and uncomfortable) time to make the relationships work.

What happened? This was all about organisational maturity. The partner organisation had well-established ways of doing things and strong internal relationships. Everyone knew what they were there to do, and how it related to everyone else. They knew that their colleagues could be trusted to do what they expected, and to back them up when necessary. That organisational maturity gave them a high degree of confidence.

My organisation, on the other hand, had none of that. Although individuals (as individuals) were highly competent and confident, there had not been time for strong relationships to develop between us. Although there would be an expectation of support from others, without having been there before certainty about its strength, timeliness and content was lacking. In those circumstances, collective confidence cannot be high. Eventually our differences were sorted out, but it might have been quicker and easier if the relative lack of organisational maturity and its consequences had been recognised at the start.

Confidence comes not just from the confidence of individuals. It is also about the strength of teamwork, and a team has to work together for some time to develop that trust and mutual confidence. When two organisations interact, expect their relative maturities to affect the outcome.

Near where I live, there is a wonderful cheese shop. It sells an amazing selection of English artisanal cheeses, as well as a variety of other delicious local produce. Not surprisingly, it is my place of choice for cheese for Christmas. It's just a pity that the customer service is not up to the standard of the cheese.

I placed my order in good time, for collection on 23 December. I duly arrived at the shop, full of anticipation, on my way home from work. The table outside groaned with goodies including beautifully-decorated cakes, rustic breads and colourful preserves. The shop is fairly simple inside, but filled with the wonderful aroma from the cheeses and from the delicious food being served in their upstairs café.

There seemed only to be one young lady serving, and she looked a bit stressed by the queue of customers; cutting, weighing and wrapping cheeses is a slow process. Still, I assumed serving me would be easy – all that should have been done already. She looked in the fridges under the cool counter; not there. She looked in another fridge; no better. Looking more stressed, she told me that she was very sorry, she couldn’t find my order; “Would you mind going away and coming back later?”

Bad move. “Yes, actually, I would. I’m on my way home from work, I've had a busy day, and I don’t want to hang around. That’s why I placed an order.” Another hunt still produced nothing.

A small lady with shoulder-length reddish hair came in – the manager. We found where my order had been written in the book, just as I had said. “Well, if you can wait, we can make up some of your order again, but I’m afraid we have none of the Tamworth left. We are completely sold out of soft cheeses.” I grumpily agreed that they had better do that, meanwhile starting to wonder where I would be able to find a good soft cheese on Christmas Eve. Then she showed me a small cheese –under 100g I would say – and said “we have one of these left. They are absolutely delicious – unfortunately I can’t give you a taste as it is the last one. They are £6.” … So that is about £60 / kg? Are you serious? No thanks.

After that, the manager lost interest. The assistant worked out the total price, and only then said “we’ll give you 10% off for the inconvenience”. I paid, and walked out with my cheese, about 20 minutes later than I had expected and in a thoroughly bad temper.

So what did I learn from these unhappy events? Observing my own feelings, first, that the longer the problem lasts, the more it takes to put it right. And second, that if you don’t do enough, you might as well do nothing.

Good customer service

The first rule of customer service is “keep your promises”. And since things will sometimes go wrong, the second rule is “When you can’t keep your promises, try to solve the problem you have caused as quickly as you can”. If the assistant had said at the start something like, “I’m really sorry, I’ll make the order up as quickly as I can. You can have a free coffee upstairs while you are waiting. What can I offer you instead of the Tamworth?” – suggesting solutions to my problems – I would probably have been satisfied, and would actually have spent more. By the time the manager showed me the expensive cheese, she needed to have given it to me, not offered to sell it to me, to compensate. And by the end, a 10% discount not only did not solve my problem but felt like adding insult to injury. A customer problem is an opportunity for free good – or bad – publicity. The choice of which is yours. [contact-form][contact-field label='Name' type='name' required='1'/][contact-field label='Email' type='email' required='1'/][contact-field label='Website' type='url'/][contact-field label='Comment' type='textarea' required='1'/][/contact-form]

What happens when an organisation grows up? Many things, but it is not so different from a child growing up: it develops organisation maturity.

As a child grows up, it develops its own habits, values, behaviours. It makes friends. It learns how to do things it could not do before. And it learns how to blend and adapt all of those things to create a consistent whole – its personality. With that comes self-confidence.

So it is with an organisation. In a young organisation – even a large one, perhaps formed from a merger – processes and structures may have been patched together un-adapted from different inheritances. Initially, the mixture of values, relationships, and so on, is unlikely to be self-consistent. Although they may be individually very experienced, managers are not used to working together, and do not know how each other will react in different circumstances. Trust takes time to develop.

Even for an established organisation, a major disruptive change in its environment can cause the same difficulties. The new environment is unfamiliar and the managers of the organisation may have varying responses. Confidence and trust in each other’s judgement in the new situation need to be re-established. Perhaps new people join the team. Processes and systems may need to be changed, because the organisation and its strategy are no longer aligned.

Nobody expects a small, young organisation to behave like a major corporation. However, with scale comes expectation. If you look like a grown-up, people expect you to behave like a grown-up and to have grown-up relationships. Just as with a child who looks much older than it is, the incongruity can cause difficulty for everyone.

Organisational self-confidence – maturity if you will – matters. When an organisation knows at all levels that ‘this is the way we do things round here’, everyone in it can stand their ground with confidence if they need to, in the knowledge that all their colleagues would back them up. Where there is underlying inconsistency, people do not have that confidence. Then it can feel as if you are standing on your own, rather than backed by a team - the whole is not greater than the sum of the parts. So an organisation in this situation needs to grow up fast.

What does it take to do something about this?

First, recognise the nature of the problem. Fundamentally the challenge is about joining things up. That makes it multi-dimensional, multi-functional, crossing all the silos. That in itself means the response has to be driven or at least supported from the top. It also means that it is best done by someone with no vested interest in the outcome. And while it will require detailed analytical work to understand and correct specific problems, it will also need influencing and people skills to ensure that the solutions are accepted and embraced.

I have worked in a number of organisations which have faced challenges of this sort, and helped them to find their way through them. If you are facing similar challenges which you would like to discuss, please contact me at david@otteryconsulting.co.uk.

Such a simple question, but what a profound difference! A recent article in HBR [http://hbr.org/2013/03/do-you-play-to-win-or-to-not-lose/ar/1 ] shows that this aspect of personality can trump others when it comes to determining fit.

Such a simple question, but what a profound difference! A recent article in HBR [http://hbr.org/2013/03/do-you-play-to-win-or-to-not-lose/ar/1 ] shows that this aspect of personality can trump others when it comes to determining fit.