Just before Christmas, I was doing some last-minute shopping in one of the Oxford Street department stores. As usual at that time of year, there was a long queue for the checkouts. When I eventually got to a till, I was surprised to see two people there. There was a young man operating the till. And there was a tall older man bagging the goods sold. Although they were busy, you could tell that they were working well together, and enjoying exchanging a few words with customers and each other when they could.

Despite this, the older man had a gravitas that you associate more with the Board room than with the tills of a busy store. Not surprising really – he was a senior manager doing a shift supporting the front-line staff at their busiest time. What was surprising (apart from him being there at all) was the easy way he appeared to be accepted as part of the team.

Here was a real “one-team” culture in action. He was not just doing what the organisation expected. He was doing what he believed in, and so it came naturally. His colleagues saw it as perfectly natural and normal too. Everyone was comfortable, and it worked.

Culture is the pattern of behaviours that people adopt in order to be accepted in a community. It is defined by what people really value, not what they say they value. In that store, people really valued working together as one team to deliver happy customers. That meant that there was nothing awkward about managers working on the tills. Actions speak louder than words, and clearly it works for them.

Just before Christmas, I was doing some last-minute shopping in one of the Oxford Street department stores. As usual at that time of year, there was a long queue for the checkouts. When I eventually got to a till, I was surprised to see two people there. There was a young man operating the till. And there was a tall older man bagging the goods sold. Although they were busy, you could tell that they were working well together, and enjoying exchanging a few words with customers and each other when they could.

Despite this, the older man had a gravitas that you associate more with the Board room than with the tills of a busy store. Not surprising really – he was a senior manager doing a shift supporting the front-line staff at their busiest time. What was surprising (apart from him being there at all) was the easy way he appeared to be accepted as part of the team.

Here was a real “one-team” culture in action. He was not just doing what the organisation expected. He was doing what he believed in, and so it came naturally. His colleagues saw it as perfectly natural and normal too. Everyone was comfortable, and it worked.

Culture is the pattern of behaviours that people adopt in order to be accepted in a community. It is defined by what people really value, not what they say they value. In that store, people really valued working together as one team to deliver happy customers. That meant that there was nothing awkward about managers working on the tills. Actions speak louder than words, and clearly it works for them.

Walking the Talk

That experience prompted me to re-read Carolyn Taylor’s “Walking the Talk”, an excellent introduction to corporate culture. Here was an organisation that has a clearly-defined culture, and knows how to maintain it by walking the talk. Sadly, in my experience most leaders are better at the talking than the walking, and in any case most organisations don’t really know what culture they want (if they think about it at all). That’s a lot of value to be losing. As a professional change manager and consultant, I get asked to advise on how to bring about cultural change in organisations. Often, part of the conversation goes something like this:

“We really need to change how we do things. We just don’t have enough hours in the day to get everything done.”

“Yes, I can see that that would be a problem. I’m sure that there is a better way. It sounds like you need to delegate more. How comfortable are you with delegating to your managers?”

“That would be fine. But the problem is, our staff don’t have enough time for everything they need to do now either.”

“Hmm. You need a change programme – which you will need time and energy to lead – but you don’t have any spare capacity, and there is nowhere you can delegate stuff to free up some. So what parts of what you do now are you willing to see not being done at all to make the change happen?”

That often produces blank looks. But you have to devote time to leading change if you want it to succeed. You also have to lead by example. You have to demonstrate that change is a sufficiently high priority for you that it displaces other things. Other people are unlikely to change what they do until they see you changing what you spend time on, not just talking about doing so.

As a professional change manager and consultant, I get asked to advise on how to bring about cultural change in organisations. Often, part of the conversation goes something like this:

“We really need to change how we do things. We just don’t have enough hours in the day to get everything done.”

“Yes, I can see that that would be a problem. I’m sure that there is a better way. It sounds like you need to delegate more. How comfortable are you with delegating to your managers?”

“That would be fine. But the problem is, our staff don’t have enough time for everything they need to do now either.”

“Hmm. You need a change programme – which you will need time and energy to lead – but you don’t have any spare capacity, and there is nowhere you can delegate stuff to free up some. So what parts of what you do now are you willing to see not being done at all to make the change happen?”

That often produces blank looks. But you have to devote time to leading change if you want it to succeed. You also have to lead by example. You have to demonstrate that change is a sufficiently high priority for you that it displaces other things. Other people are unlikely to change what they do until they see you changing what you spend time on, not just talking about doing so.

Change needs time

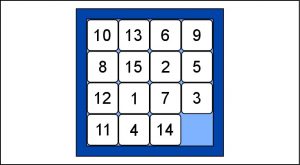

Think of it like a sliding-tile puzzle. In a 4 x 4 puzzle there are 15 tiles, so that there is always one space to move the next tile into. That gives enough flexibility to rearrange all the tiles into the right pattern. If there were 16 tiles – completely filling the frame – nothing could move at all. You have to find an empty space in your time, like the missing tile, to be able to rearrange your organisational tiles. Like many things in life, this is just about priorities. If change is high enough up your priority list, it will displace other activities to create the necessary space. If it isn’t, it is best not to start. This seasonal message will help you to remember! A few days ago I went to a concert. Not a typical one though. I was attracted by the lines “…even if you know nothing at all about…”, and “We know all people will bring intelligent ears with them.” An opportunity to experience something new.

The music was by Karlheinz Stockhausen, a pioneer of electronic music in the 1950s who had a major influence on the world of pop as well as on ‘serious’ music (he is one of the faces on the cover of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper album). It was an extraordinary evening.

Some people might not regard what we heard as music at all, but just a jumble of noises. Beforehand, I might have been one of them. What astonished me was that the whole experience was completely enthralling. The sound as you might hear it from loudspeakers at home was only one element. The virtuosic skill of the performers creating this incredibly complex sound was humbling to watch. The continually-changing spatial arrangement of the sound, and the atmosphere created by being with all those other ‘intelligent ears’ added other dimensions. Somehow, the jumble started to make sense. It was an evening to remember for a long time.

A few days ago I went to a concert. Not a typical one though. I was attracted by the lines “…even if you know nothing at all about…”, and “We know all people will bring intelligent ears with them.” An opportunity to experience something new.

The music was by Karlheinz Stockhausen, a pioneer of electronic music in the 1950s who had a major influence on the world of pop as well as on ‘serious’ music (he is one of the faces on the cover of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper album). It was an extraordinary evening.

Some people might not regard what we heard as music at all, but just a jumble of noises. Beforehand, I might have been one of them. What astonished me was that the whole experience was completely enthralling. The sound as you might hear it from loudspeakers at home was only one element. The virtuosic skill of the performers creating this incredibly complex sound was humbling to watch. The continually-changing spatial arrangement of the sound, and the atmosphere created by being with all those other ‘intelligent ears’ added other dimensions. Somehow, the jumble started to make sense. It was an evening to remember for a long time.

Its worth the risk

If you have never tried something, you can’t know what you are missing. Maybe it won’t work for you. But just as likely you will find new perspectives and insights that you could not have imagined otherwise. It is worth the risk. I’ve just started trying to organise a local walking group for alumni from my university. The initial process was simple: I wrote an email asking for interest, the alumni office sent it out to people on their database with postcodes in the local area, and I collected the responses.

The outcome has been pleasantly surprising. The response rate was over 10%, which under almost any circumstances I would think was a fantastic return for a single ‘cold call’ message out of the blue. But almost as surprising was the proportion of responses which included words along the lines of ‘what a good idea’ with at least the implication of ‘why has no-one suggested this before?’. It seemed as if all that latent demand was just sitting there waiting to be tapped.

I’ve just started trying to organise a local walking group for alumni from my university. The initial process was simple: I wrote an email asking for interest, the alumni office sent it out to people on their database with postcodes in the local area, and I collected the responses.

The outcome has been pleasantly surprising. The response rate was over 10%, which under almost any circumstances I would think was a fantastic return for a single ‘cold call’ message out of the blue. But almost as surprising was the proportion of responses which included words along the lines of ‘what a good idea’ with at least the implication of ‘why has no-one suggested this before?’. It seemed as if all that latent demand was just sitting there waiting to be tapped.

Innovation

That set me thinking about how innovation happens. This was not a complicated idea; anyone could have tried it. But no one else did. So what does innovation need? I think there are usually two ingredients. The first is some kind of investment. Often that is financial, but (as in this case) it may just be time and emotional energy. Investment means that you have to put something in, but that success is uncertain and although you may be rewarded well, you may also get nothing back. So the innovator must be willing to take that risk. The second is some relevant knowledge. I had done something similar before, so I knew an easy way to reach my target audience. That knowledge reduced both my investment of time and the risk of failure I saw. I might have been willing to try anyway, but this made it more likely that I would. Certainly I was more likely to try than people without that knowledge. All of us prioritise what we will spend our time on, largely based on our perception of the risk-reward balances of our options. Making innovation happen is usually not about brilliant ideas; it is far more about simply taking the risk to put a simple idea into practice. There is little you can do to change someone’s appetite for risk. If you want to encourage innovation, then, try to find ways to reduce the risk that they see. I was once asked in an interview about tough decisions I’ve made, and how I made them. I understand why it might be thought important in the selection process: it seems like a good question. Doesn’t it tell you something about the individual’s ability to cope in difficult situations? However, on reflection I’m less convinced!

Thinking back over a number of my roles, I realised (to my surprise) that most of the important decisions I have taken have not seemed tough at all. By ‘tough’ I mean difficult to make; they may still have been hard to implement. Conversely, tough decisions (on that definition) have often not been particularly important.

I was once asked in an interview about tough decisions I’ve made, and how I made them. I understand why it might be thought important in the selection process: it seems like a good question. Doesn’t it tell you something about the individual’s ability to cope in difficult situations? However, on reflection I’m less convinced!

Thinking back over a number of my roles, I realised (to my surprise) that most of the important decisions I have taken have not seemed tough at all. By ‘tough’ I mean difficult to make; they may still have been hard to implement. Conversely, tough decisions (on that definition) have often not been particularly important.

What makes tough decisions?

So what makes a decision tough? Often it is when there are two potentially conflicting drivers for the decision which can’t be measured against each other. Most commonly, it is when my rational, analytical side is pulling me one way – and my emotional, intuitive side is pulling another. Weighing up the pros and cons of different choices is relatively easy when it can be an analytical exercise, but that depends on comparing apples with apples. When two choices are evenly balanced on that basis, your choice will make little difference, so there is no point agonising about it. The problem comes when the rational comparison gives one answer, but intuitively you feel it is wrong. Comparing a rational conclusion with an emotional one is like comparing apples and roses – there is simply no basis for the comparison. When they are in conflict, you must decide (without recourse to analysis or feeling!) whether to back the rational conclusion or the intuitive one. A simple example is selecting candidates for roles. Sometimes a candidate appears to tick all the boxes convincingly, but intuition gives a different answer. On the rare occasions when I have over-ridden my intuition, it has usually turned out to be a mistake. Based on experience, then, I know that I should normally go with intuition, however hard that feels. We are all different though. Perhaps everyone has to find out from their mistakes how to make their own tough decisions. What we should not do is confuse how hard it is to make a decision with how important it is.

It was only in the latter stages of the referendum campaign that the penny dropped for me. I realised that the reason that the campaign was so much about emotion and so little about facts and likely consequences was that, whatever its ostensible purpose, the referendum had come to be about who we are. My identity is what I believe it to be, and what those I identify with believe it to be. The outcome of a referendum does not, cannot, change that, even if it can lead to a change of status.

It would obviously be nonsense if, when you asked someone whether they would be best off staying married or getting divorced, they stated their gender as the answer. Politicians have allowed a question about relationship to be given an answer about identity. Apples and oranges. In so doing they have shot themselves – and at the same time the whole country – in the foot.

How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

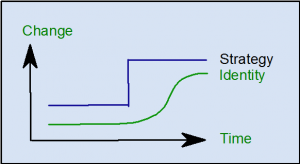

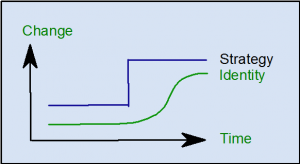

Identity and change

There is a profound lesson about change there. Identity is perhaps the ‘stickiest’ phenomenon in culture, because belonging is so fundamental to our sense of security. A change project is often perceived as changing in some way the identity of that to which we belong. However, peoples’ sense of identity changes much more slowly than the strategy. If we do not take steps to bridge the identity gap while people catch up, it is the relationship which is in for trouble. How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.  Planet K2 shared this great TED talk about how limitations can help creativity. But how is that relevant to management?

As managers, we always have to work within many limitations: it is the nature of the world we work in. Contracts of all kinds; laws and regulations; stakeholder wishes; all constrain the freedom we have to act. If we see our job as managers being to make sure that we comply with all these requirements – some of which may well be conflicting, making that task ultimately impossible – there is a good chance we will start a downwards spiral of attempting ever-tighter control while only making things worse, as artist Phil Hansen found. We become more and more stressed, and less and less able to meet all those requirements.

How much better to recognise that while the limitations rule out some options, those very limitations can help us to focus our imaginations on the many other options which we may not have considered, but which remain available (and which, as Hansen found, can still present an overwhelming range of possibilities). When you squeeze the balloon, it pops out somewhere else. That requires us to have the courage to be creative, to try new approaches which have some risk of failure – but that makes success all the more satisfying and rewarding, as well as helping to free us to continue down the route of creativity.

Hansen found that what seemed to be the end of his dream of a creative life was in fact the door to whole new worlds of creativity. Rather than try too hard to work within our constraints, let’s use them to help us find the ways to better solutions, as he did.

Planet K2 shared this great TED talk about how limitations can help creativity. But how is that relevant to management?

As managers, we always have to work within many limitations: it is the nature of the world we work in. Contracts of all kinds; laws and regulations; stakeholder wishes; all constrain the freedom we have to act. If we see our job as managers being to make sure that we comply with all these requirements – some of which may well be conflicting, making that task ultimately impossible – there is a good chance we will start a downwards spiral of attempting ever-tighter control while only making things worse, as artist Phil Hansen found. We become more and more stressed, and less and less able to meet all those requirements.

How much better to recognise that while the limitations rule out some options, those very limitations can help us to focus our imaginations on the many other options which we may not have considered, but which remain available (and which, as Hansen found, can still present an overwhelming range of possibilities). When you squeeze the balloon, it pops out somewhere else. That requires us to have the courage to be creative, to try new approaches which have some risk of failure – but that makes success all the more satisfying and rewarding, as well as helping to free us to continue down the route of creativity.

Hansen found that what seemed to be the end of his dream of a creative life was in fact the door to whole new worlds of creativity. Rather than try too hard to work within our constraints, let’s use them to help us find the ways to better solutions, as he did.

I’ve just been asked by some consultants I’m working with to give feedback for their annual appraisals. As usual there is a standard set of questions they need addressed – and one of them is about leadership. That seems a tough ask for someone junior who has only started recently, and set me thinking about how I could help them. Here’s what I said.

Leadership is different for every individual. Everyone has their own personality, and so everyone has to do it in their own way. Why? It’s very simple.

Leadership means that people are willing to follow you, and for that to happen, two things are necessary: people must trust you, and you must have something to say.

Trust comes when you behave with integrity. Everything you do is consistent, both with your values and with your personality, so people have confidence about outcomes. You are ‘authentic’. Everyone has their own personality, so everyone’s leadership is different. If you try to lead the way someone else does, you are inevitably trying to be consistent with their personality and not with your own. Even if you can do it, you will feel uncomfortable. You will come over as not authentic, and you won’t be fully trusted. As Oscar Wilde said, “Be yourself; everyone else is already taken!”

Leadership is for everyone

Everyone has something to say. We all have unique experiences starting from our earliest days, and it is human nature to use the stories of our past experiences to help us decide how to deal with new situations. Everyone has insights they can contribute, although of course the more experience you have the more you have to offer. If everyone can do these two things, leadership is not just for Leaders with a capital L. Leadership is about having the confidence to be yourself, and to share whatever your experience tells you about the situation you are in. Followers will follow!

The unexpected death this week of Bob Crow, leader of the RMT Union (which represents many London Underground train drivers amongst others) has prompted quite a bit of media comment over the last few days. Tributes from industrial and political leaders have expressed sincere sadness, despite what his militant public persona might have led you to expect.

I never met Bob Crow, but it seems to me that he grasped more clearly than many that what most people want in their leaders is passion and an appeal to their emotions. At a time of generally falling Union membership, he doubled RMT membership, and then doubled it again, over a decade. I doubt that he could have done that by making a careful rational case. Stack that up against managers who – as public servants, charged with careful management of public money – are obliged to make their arguments rationally. Can you imagine what would have happened if politicians had incited Londoners to picket RMT headquarters when the tube went on strike? It is hardly surprising that he made an impact.

Recalling other powerful Union figures of the past – Arthur Scargill, say - isn’t that instinctive understanding of emotional leadership and the power of passion something they had in common? And perhaps the reason we now have a much less unionised and strike-prone world than we did is in part because union leaders have become less demonstrably passionate.

We need leaders who are passionate about their cause – whether in politics, in industry, or in unions – because passion is what galvanises the led. Whichever side of the argument you are on, we need more leaders who do that, as Bob Crow did.

[contact-form][contact-field label='Name' type='name' required='1'/][contact-field label='Email' type='email' required='1'/][contact-field label='Website' type='url'/][contact-field label='Comment' type='textarea' required='1'/][/contact-form]