The other day I passed a set of temporary traffic lights. Hardly an unusual occurrence in a modern city! This was a nice modern set, with the lights made up of an array of LEDs. That is of course a great improvement. Apart from the environmental benefits of being low-energy and long-lasting, the light area is evenly bright all over. And there can be no problem with low sun reflecting off the back mirror so it is hard to tell which colour is illuminated.

What struck me, however, was that the LEDs were carefully arranged in a circular pattern, mimicking the traditional look of traffic lights. This is clearly not the most efficient way of arranging them. That would be a hexagonal pattern, but of course you cannot produce what looks like a neat circular outline that way.

There is no reason why in an LED system each colour of light has to be round. They could just as well be hexagonal, or any other convenient shape. A hexagon would clearly match a hexagonal pattern better. Indeed, there could be advantage in making each colour a different shape, to help the colour-blind. They make the lights round because that is how we expect traffic lights to look.

The other day I passed a set of temporary traffic lights. Hardly an unusual occurrence in a modern city! This was a nice modern set, with the lights made up of an array of LEDs. That is of course a great improvement. Apart from the environmental benefits of being low-energy and long-lasting, the light area is evenly bright all over. And there can be no problem with low sun reflecting off the back mirror so it is hard to tell which colour is illuminated.

What struck me, however, was that the LEDs were carefully arranged in a circular pattern, mimicking the traditional look of traffic lights. This is clearly not the most efficient way of arranging them. That would be a hexagonal pattern, but of course you cannot produce what looks like a neat circular outline that way.

There is no reason why in an LED system each colour of light has to be round. They could just as well be hexagonal, or any other convenient shape. A hexagon would clearly match a hexagonal pattern better. Indeed, there could be advantage in making each colour a different shape, to help the colour-blind. They make the lights round because that is how we expect traffic lights to look.

Features that get overlooked

When looking at business improvements, there are usually aspects of the status quo which we retain and aspects which we decide to change. Some features are like the colours of traffic lights. The confusion caused by changing them would a serious problem, and we know we must not. Others may be like the type of light source. It is obvious that a change is possible if it is beneficial. However, some are like the shape of lights, which we are so used to that we forget to challenge them. We always need to be on the lookout for features kept because we forgot they could be changed rather than for good reason. A long time ago, I proposed an important change to a committee of senior colleagues. The overall intent was hardly arguable, and I had carefully thought out the details. Overall, it got a good hearing. But then the trouble started. One manager picked on a point of detail which he didn’t like. OK, I thought, I can find a way round that. But then other managers piled in, some supporting my position on that, but objecting to different details. The discussion descended into a squabble about detailed points on which no-one could agree, and as a result the whole project was shelved despite its overall merits.

I learnt an important lesson from that experience. When a collective decision is required, detail is your enemy. Most projects will have – or at least may be perceived to have – some negative impacts on some people, even though overall they benefit everyone. Maybe someone loses autonomy in some area, or needs to loan some staff. Maybe there is some overlap with a pet project of their own. Whatever the reason, providing detail at the outset makes those losses visible, and can lead to opposition based on self-interest (even if that is well-concealed) which kills the whole project. As we all know, you can’t negotiate with a committee.

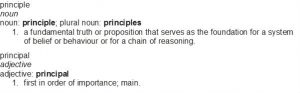

So what is the answer? The approach I have found works best is to start by seeking agreement for general principles with which the implementation must be consistent. The absence of detail means that the eventual impacts on individual colleagues are uncertain, and consequently the discussion is more likely to stay focused on the bigger picture. Ideally you are given authority to implement within the approved principles. But even if you have to go back with a detailed plan, once the committee has approved the outcome and the principles to be followed it is much harder for them to reject a solution that sticks to those, let alone to kill the project.

Looking at the wider world, perhaps the Ten Commandments of the Bible provide a good example of this approach. For a more business-relevant example, see my earlier posts on the principles behind good internal governance.

More generally, defining top-level principles is also the key to delegating decision-making to local managers. It means that they can make decisions which take proper account of local conditions, while ensuring that decisions made by different managers in different areas all have an underlying consistency.

A long time ago, I proposed an important change to a committee of senior colleagues. The overall intent was hardly arguable, and I had carefully thought out the details. Overall, it got a good hearing. But then the trouble started. One manager picked on a point of detail which he didn’t like. OK, I thought, I can find a way round that. But then other managers piled in, some supporting my position on that, but objecting to different details. The discussion descended into a squabble about detailed points on which no-one could agree, and as a result the whole project was shelved despite its overall merits.

I learnt an important lesson from that experience. When a collective decision is required, detail is your enemy. Most projects will have – or at least may be perceived to have – some negative impacts on some people, even though overall they benefit everyone. Maybe someone loses autonomy in some area, or needs to loan some staff. Maybe there is some overlap with a pet project of their own. Whatever the reason, providing detail at the outset makes those losses visible, and can lead to opposition based on self-interest (even if that is well-concealed) which kills the whole project. As we all know, you can’t negotiate with a committee.

So what is the answer? The approach I have found works best is to start by seeking agreement for general principles with which the implementation must be consistent. The absence of detail means that the eventual impacts on individual colleagues are uncertain, and consequently the discussion is more likely to stay focused on the bigger picture. Ideally you are given authority to implement within the approved principles. But even if you have to go back with a detailed plan, once the committee has approved the outcome and the principles to be followed it is much harder for them to reject a solution that sticks to those, let alone to kill the project.

Looking at the wider world, perhaps the Ten Commandments of the Bible provide a good example of this approach. For a more business-relevant example, see my earlier posts on the principles behind good internal governance.

More generally, defining top-level principles is also the key to delegating decision-making to local managers. It means that they can make decisions which take proper account of local conditions, while ensuring that decisions made by different managers in different areas all have an underlying consistency.

I once worked for a young organisation with big ambitions. The managers were all highly experienced, but had only recently come together as a team. They decided to contract with a long-established and very stable international firm to help with operations.

I don’t think anybody was expecting what happened next. The partner firm arrived, and immediately started to call the shots. Needless to say, hackles rose amongst my colleagues – we were the customer, after all: isn’t the customer always right? It took some considerable (and uncomfortable) time to make the relationships work.

What happened? This was all about organisational maturity. The partner organisation had well-established ways of doing things and strong internal relationships. Everyone knew what they were there to do, and how it related to everyone else. They knew that their colleagues could be trusted to do what they expected, and to back them up when necessary. That organisational maturity gave them a high degree of confidence.

My organisation, on the other hand, had none of that. Although individuals (as individuals) were highly competent and confident, there had not been time for strong relationships to develop between us. Although there would be an expectation of support from others, without having been there before certainty about its strength, timeliness and content was lacking. In those circumstances, collective confidence cannot be high. Eventually our differences were sorted out, but it might have been quicker and easier if the relative lack of organisational maturity and its consequences had been recognised at the start.

Confidence comes not just from the confidence of individuals. It is also about the strength of teamwork, and a team has to work together for some time to develop that trust and mutual confidence. When two organisations interact, expect their relative maturities to affect the outcome.

Have you ever noticed that the fruit and nuts in your breakfast muesli tend to stay at the top of the packet? So that when you are getting toward the end of the packet, you are usually left with mostly the boring bits?

There is a simple explanation. When there are many large lumps (the fruit and nuts) together, they have large holes in between them, and smaller lumps (the oats) can fall through the holes. When many small lumps are together, they have small holes in between them, so large lumps can’t fall through. Consequently, with gentle shaking there is a tendency for the large and small lumps to separate, with the large lumps at the top.

Interesting, but so what? Well, perhaps the same sort of thing happens with the order of work activities. The interesting, strategic lumps stay at the top and get done first. The boring – or difficult – bits may fall through the cracks, or at least get left to others or to later. The trouble is that to have a nutritionally balanced diet, we need the whole mixture, not just the exciting bits. Good delivery requires us to stick to doing things in the best order, even when that means tackling early some activities we would rather leave till later.

Have you ever noticed that the fruit and nuts in your breakfast muesli tend to stay at the top of the packet? So that when you are getting toward the end of the packet, you are usually left with mostly the boring bits?

There is a simple explanation. When there are many large lumps (the fruit and nuts) together, they have large holes in between them, and smaller lumps (the oats) can fall through the holes. When many small lumps are together, they have small holes in between them, so large lumps can’t fall through. Consequently, with gentle shaking there is a tendency for the large and small lumps to separate, with the large lumps at the top.

Interesting, but so what? Well, perhaps the same sort of thing happens with the order of work activities. The interesting, strategic lumps stay at the top and get done first. The boring – or difficult – bits may fall through the cracks, or at least get left to others or to later. The trouble is that to have a nutritionally balanced diet, we need the whole mixture, not just the exciting bits. Good delivery requires us to stick to doing things in the best order, even when that means tackling early some activities we would rather leave till later.

Is your high-level strategy adequately joined up with the realisation of the vision on the ground?

The people who are interested in the strategy are often not very interested in managing the details, and perhaps are frustrated by the questions they are asked by implementers.

The people who are delegated the task of dealing with the detail frequently do not have the strategic ability, or lack the information, to understand fully the context for what they have been asked to do.

The consequence is a gap between intent and delivery which is often filled with misunderstandings, confusion, misalignment and ultimately frustration.

Is your high-level strategy adequately joined up with the realisation of the vision on the ground?

The people who are interested in the strategy are often not very interested in managing the details, and perhaps are frustrated by the questions they are asked by implementers.

The people who are delegated the task of dealing with the detail frequently do not have the strategic ability, or lack the information, to understand fully the context for what they have been asked to do.

The consequence is a gap between intent and delivery which is often filled with misunderstandings, confusion, misalignment and ultimately frustration.

A joined-up strategy

Overcoming this requires a clear shared understanding of the big picture. It is not just about communications, although that is important. As they say, the devil is in the detail, so it requires working together to think through the implications of strategy – the roles cannot be separated. Both the big picture and the detail matter, but how you join them up is critical: the whole can be greater than the sum of the parts, but only if it really is a whole.Yesterday I spent the morning at WBMS, in a fascinating workshop run by Quirk Solutions exploring the value of ‘Wargaming’ as a way of testing the resilience of a strategy and related plans before putting them into effect.

Wargaming, as you might imagine, is based on the process developed by the military to evaluate their plans, but that is where any direct connection to anything military ends. If you called the process something else, nothing about it would tell you its origins. And in practice, it is really a somewhat more formalised and disciplined extension of testing approaches which you may well already use to some extent. Where Chis Paton and his team at Quirk really add value is in their in-depth experience of what works, and highly-polished skills for facilitating the process to make it maximally effective.

I took away a number of key ideas for running a good process which I thought it would be worth sharing.

Wargaming

The process is based around two teams: the Blue (plan-owning) Team and the Red (plan-challenging) Team. Although that sounds similar to the common approach of ‘Red Team Review’ for proposal improvement, in this process it is made more effective by asking each Red Team player to represent the views of a major interested party or parties. This makes for a much more engaged and lively process, better bringing out emotive issues. It can also bring out the important potential conflicts between different interests which may otherwise be ‘averaged out’. At least some of the Red Team can be externals – where there are no commercial issues, they could even be the relevant interest groups themselves! – which is clearly likely to help avoid blind spots. Even in a brief exercise, it was clear that the role-playing approach could bring much greater richness to the output. The process is also iterative: the Blue Team present their outline plan (best not to develop too much detail early, as it is likely to change!); the Red Team make challenges back from their ‘interest’ perspectives; the Blue Team re-work the proposal to address as many of the issues as possible; further challenge, and so on. Clearly in a relatively brief review meeting, there will be very limited time for further analysis or data gathering between iterations, so the objective is not a finished plan, but the best possible framework to take away and work up, together with lists of actions and owners. That leads me to my final point: While a Red Team Review would normally be looking at a more-or-less finished proposal, the process we tested will add most value early in the process of development. No-one likes to make significant changes to a plan that they have put a lot of effort into, however important, and that may well lead to the smallest adaptation possible, rather than the best. Thanks WBMS and Quirk for organising a stimulating event! I went to a fascinating talk by Adam Hoyle, Managing Director, Tradax Group Ltd, on Corporate Best Practice in Public Sector Bidding. I thought there were a number of lessons that apply more generally to running all kinds of projects that would be worth sharing.

I went to a fascinating talk by Adam Hoyle, Managing Director, Tradax Group Ltd, on Corporate Best Practice in Public Sector Bidding. I thought there were a number of lessons that apply more generally to running all kinds of projects that would be worth sharing.

Seven best practice tips

- Don’t start projects unless they align with your overall strategy

- Make sure you have thought through exactly what decision-making authority each person involved should have, and that this has been clearly communicated and understood

- Give everyone involved a clear written briefing pack at the start, providing them with all the basic information about the project that they will require

- Standardise what you can – but everything that is standardised needs an owner who takes their ownership seriously

- Think hard about what information would really make a difference to your performance if you had it, and work creatively (legally of course) to get it – for example using FoI requests

- Use the information you have intelligently – there is probably much more that you can learn than is immediately obvious, if you put it all together

- Transitions between teams – for example on winning a bid, or starting to operate an asset – are high-risk boundaries, which need careful planning to make sure they go smoothly

For the last few weeks I have been posting about general principles of governance. Let’s turn to a practical example: How do those principles apply to programme management? There is of course no one ‘right way’ – it depends on the context. However, there definitely are ‘wrong’ ways, and they are all too common!

Most programmes have a Programme Director, and most have a Programme Board. What are their roles, and how should they be related?

Programme Board

The Programme Board should be a fundamental part of the governance structure. There would be no point in it being there unless it makes decisions. To do that, it must be given authority by some other body, which must itself have the authority to do that. Programme Boards typically have as part of their role resolving cross-functional issues for the programme. Consequently, they will normally be set up to report to a committee within the governance structure which itself has cross-functional representation. If the Programme Board is unable to resolve an issue which comes to it, normally its parent will need to. If a Programme Board were to report to an individual, it would be hard to see how that individual could more effectively resolve any cross-functional issue that had to be escalated.Programme Director

The Programme Director’s role will vary in detail between programmes, but fundamentally he or she is the person accountable for making sure that the expected outcomes of the programme are delivered within the constraints agreed. That leads us to two further points. First, if they are accountable, who will hold them to account? That is another part of the role of the Programme Board. The Programme Director will present progress reports, papers for decision, etc to the Programme Board, to enable them to do that. A corollary is that the Programme Director should be appointed, or at least confirmed, by the Programme Board, which will also delegate authority. If things are not going well, it is the Programme Board that must decide whether a change of Programme Director is required. Second, what is the nature of the relationship between the Programme Director and the Programme Board? Essentially it is like a contract. The Programme Board is the customer for the programme, approving the programme requirements. The Programme Director represents the delivery team - the contractor, if you will - and needs to make sure that sufficient time and resources are allocated to the programme to deliver the requirements. Clearly making the two join up may require negotiation. If there are subsequent changes to requirements, agreeing how to accommodate these – extra resource, recognising more risk, delay or reduced quality – will require a further negotiation. Remember, accountability and authority need to go together. Just as with the CEO and a company Board, it is clear that the Programme Director has a fundamentally different role to that of the Programme Board, and to blur these distinctions will introduce conflicts of interest. Of course the Programme Director will normally attend Programme Boards, although that does not mean that they have to be a member (and the different roles are clearer if they are not). Either way, though, they should never be the Chair: they would have a clear conflict of interest. At best they would be tempted to steer the agenda away from certain issues, and it would become impossible for the Board to be effective in holding them to account. No-one should be asked to mark their own homework! It follows that the members of the Programme Board should not normally be junior to the Programme Director, and certainly should not be his or her direct reports. Of course there is a place for meetings of the Programme Team – but those are progress meetings, not Programme Boards. Do your Programme Boards follow these rules? A recent client experience came to mind when I read the following blog post:

http://sethgodin.typepad.com/seths_blog/2013/12/broken-english.html.

Seth says “you will be misunderstood”, and broadly speaking I agree with him: we all interpret what we hear in the context of our own experiences, however careful the speaker, and those experiences are all different. But I think is important to remember that there are degrees of misunderstanding; not all misunderstandings are equal.

My client had started a change project which was running into difficulty. As I started to talk to his staff, it became clear that they all had slightly different understandings of the objectives of the project. Not only did that mean that there was confusion about where they were trying to get to as a whole, but it also meant that the various workstreams were unlikely to join up.

You won’t be surprised to hear that there was not much formal documentation for the project. I’m sure my client felt he had explained what he wanted very clearly – and if he had been on the receiving end, I am certain that he would have understood himself perfectly. But his audience was not him, and he had not taken the additional step of asking his audience to play back to him to check their understanding.

One of the most important tasks for any project manager is to make sure that project objectives are defined clearly, and that everyone understands them. A key skill for project managers is therefore to be able to put things into simple, unambiguous language that fits the background and culture of everyone in the team. They must be good translators: there may still be some misunderstandings, but if they can’t reduce them to a very low minimum by adapting their language (and their listening) to their different audiences, they will not be effective. Just look what happened at Babel!

A recent client experience came to mind when I read the following blog post:

http://sethgodin.typepad.com/seths_blog/2013/12/broken-english.html.

Seth says “you will be misunderstood”, and broadly speaking I agree with him: we all interpret what we hear in the context of our own experiences, however careful the speaker, and those experiences are all different. But I think is important to remember that there are degrees of misunderstanding; not all misunderstandings are equal.

My client had started a change project which was running into difficulty. As I started to talk to his staff, it became clear that they all had slightly different understandings of the objectives of the project. Not only did that mean that there was confusion about where they were trying to get to as a whole, but it also meant that the various workstreams were unlikely to join up.

You won’t be surprised to hear that there was not much formal documentation for the project. I’m sure my client felt he had explained what he wanted very clearly – and if he had been on the receiving end, I am certain that he would have understood himself perfectly. But his audience was not him, and he had not taken the additional step of asking his audience to play back to him to check their understanding.

One of the most important tasks for any project manager is to make sure that project objectives are defined clearly, and that everyone understands them. A key skill for project managers is therefore to be able to put things into simple, unambiguous language that fits the background and culture of everyone in the team. They must be good translators: there may still be some misunderstandings, but if they can’t reduce them to a very low minimum by adapting their language (and their listening) to their different audiences, they will not be effective. Just look what happened at Babel!

Spotted from the Portsmouth to Cherbourg ferry – a container ship clearly branded ‘Fyffes’. To anyone in the UK (I’m not sure about elsewhere), that means only one thing: bananas.

How many bananas would you get on a banana boat? The banana boxes you see in supermarkets must be about 50cm x 35cm x 20cm (1/30 cubic metre) and I’d guess that they might hold about 100 bananas – so that’s something like 3000 bananas per cubic metre.

A standard container is about 2.4m x 2.4m x 12m, or 72 cubic metres – so that makes about 200,000 bananas per container. Its hard to tell how many containers there are on the boat, but perhaps 100? So maybe 20,000,000 bananas per ship – one between three for the entire population of the UK. That means we need a ship-load of bananas to arrive in Britain every day to provide the average 2 bananas a week that we each eat.

There are several interesting thoughts that follow from that. The first is simply the incredible logistical feat of providing that many ripe bananas, day in, day out, to shops across the land. Demand takes little account of seasons or weather, and bananas are quite easily damaged. Developing processes which can deliver that volume, in good condition and at the price people expect to pay, while having the resilience to cope with the vagaries of nature, is an impressive achievement. There is little to distinguish between one banana and another though – so its only getting those processes optimised that enables you to compete.

Another is the power of such rough and ready estimates. Starting from easy observations and guesses that anyone could make, we can get a pretty good estimate of shipping requirements: we might be 2x too big or small, but probably not much worse than that. Frequently there is no need for high precision, at least to start with, but the courage to estimate is not always easily found.

A final thought is the power of those little labels, When I was a child, it seemed as though every bunch of bananas had a Fyffes label on it. Fifty years later, the association is still instant. I’m not sure how that creates value for Fyffes (does it?), but the effect is unmistakable!