I was once asked in an interview about tough decisions I’ve made, and how I made them. I understand why it might be thought important in the selection process: it seems like a good question. Doesn’t it tell you something about the individual’s ability to cope in difficult situations? However, on reflection I’m less convinced!

Thinking back over a number of my roles, I realised (to my surprise) that most of the important decisions I have taken have not seemed tough at all. By ‘tough’ I mean difficult to make; they may still have been hard to implement. Conversely, tough decisions (on that definition) have often not been particularly important.

I was once asked in an interview about tough decisions I’ve made, and how I made them. I understand why it might be thought important in the selection process: it seems like a good question. Doesn’t it tell you something about the individual’s ability to cope in difficult situations? However, on reflection I’m less convinced!

Thinking back over a number of my roles, I realised (to my surprise) that most of the important decisions I have taken have not seemed tough at all. By ‘tough’ I mean difficult to make; they may still have been hard to implement. Conversely, tough decisions (on that definition) have often not been particularly important.

What makes tough decisions?

So what makes a decision tough? Often it is when there are two potentially conflicting drivers for the decision which can’t be measured against each other. Most commonly, it is when my rational, analytical side is pulling me one way – and my emotional, intuitive side is pulling another. Weighing up the pros and cons of different choices is relatively easy when it can be an analytical exercise, but that depends on comparing apples with apples. When two choices are evenly balanced on that basis, your choice will make little difference, so there is no point agonising about it. The problem comes when the rational comparison gives one answer, but intuitively you feel it is wrong. Comparing a rational conclusion with an emotional one is like comparing apples and roses – there is simply no basis for the comparison. When they are in conflict, you must decide (without recourse to analysis or feeling!) whether to back the rational conclusion or the intuitive one. A simple example is selecting candidates for roles. Sometimes a candidate appears to tick all the boxes convincingly, but intuition gives a different answer. On the rare occasions when I have over-ridden my intuition, it has usually turned out to be a mistake. Based on experience, then, I know that I should normally go with intuition, however hard that feels. We are all different though. Perhaps everyone has to find out from their mistakes how to make their own tough decisions. What we should not do is confuse how hard it is to make a decision with how important it is.In the old days, efficiency (doing things right) ruled. You made money by having more efficient processes than competitors, so your margin was higher on the same price. Scale was rewarded, because it brought efficiency, encouraging huge companies and standardised products. Flexibility was your enemy.

Now, technology has changed everything. Just because it is possible, effectiveness (doing the right thing) will rule. The customer will always be right, whatever they want. Can you imagine people now accepting Henry Ford’s statement that people could have any colour they wanted, so long as it was black? Scale and efficiency is not the only thing that matters any more – in this new world, value comes from responsiveness. Success requires using connections, building a community with customers and suppliers, and being creative.

In the days when efficiency led, market domination was the objective, because that was what allowed you to hold onto your “most efficient producer” badge. In the new world, domination is not the only determinant of success. Your company needs to be like a lumberjack on a log flume – constantly moving to stay on top despite the logs rolling, and needing the agility that comes most easily to small companies to do so.

Use consultants and interims for ideas and flexibility

This model lends itself readily to the de-centralised organisation, using consultants, interims, and other forms of flexible working to provide the skills needed when they are needed. To do this well, the organisation needs to be networked and connected; old-style hierarchies, linear processes and so on inhibit the flexibility required. In this post-Brexit-vote world, where no-one quite knows where we are going or what it will mean, that flexibility to adapt rapidly as the shape of the future emerges will be even more important. Winning will depend on having a culture which embraces flexibility and adapts to change. Darwin had a phrase for it: survival of the fittest. The species that survived were the ones with most variability. Work flexibly; bring in and try out new ideas; find better ways to succeed. Voting to be dinosaurs can’t change the laws of nature.It was only in the latter stages of the referendum campaign that the penny dropped for me. I realised that the reason that the campaign was so much about emotion and so little about facts and likely consequences was that, whatever its ostensible purpose, the referendum had come to be about who we are. My identity is what I believe it to be, and what those I identify with believe it to be. The outcome of a referendum does not, cannot, change that, even if it can lead to a change of status.

It would obviously be nonsense if, when you asked someone whether they would be best off staying married or getting divorced, they stated their gender as the answer. Politicians have allowed a question about relationship to be given an answer about identity. Apples and oranges. In so doing they have shot themselves – and at the same time the whole country – in the foot.

How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

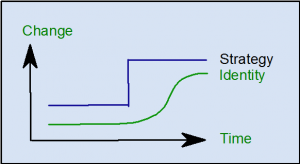

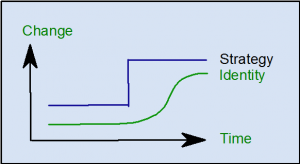

Identity and change

There is a profound lesson about change there. Identity is perhaps the ‘stickiest’ phenomenon in culture, because belonging is so fundamental to our sense of security. A change project is often perceived as changing in some way the identity of that to which we belong. However, peoples’ sense of identity changes much more slowly than the strategy. If we do not take steps to bridge the identity gap while people catch up, it is the relationship which is in for trouble. How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about. A long time ago, I proposed an important change to a committee of senior colleagues. The overall intent was hardly arguable, and I had carefully thought out the details. Overall, it got a good hearing. But then the trouble started. One manager picked on a point of detail which he didn’t like. OK, I thought, I can find a way round that. But then other managers piled in, some supporting my position on that, but objecting to different details. The discussion descended into a squabble about detailed points on which no-one could agree, and as a result the whole project was shelved despite its overall merits.

I learnt an important lesson from that experience. When a collective decision is required, detail is your enemy. Most projects will have – or at least may be perceived to have – some negative impacts on some people, even though overall they benefit everyone. Maybe someone loses autonomy in some area, or needs to loan some staff. Maybe there is some overlap with a pet project of their own. Whatever the reason, providing detail at the outset makes those losses visible, and can lead to opposition based on self-interest (even if that is well-concealed) which kills the whole project. As we all know, you can’t negotiate with a committee.

So what is the answer? The approach I have found works best is to start by seeking agreement for general principles with which the implementation must be consistent. The absence of detail means that the eventual impacts on individual colleagues are uncertain, and consequently the discussion is more likely to stay focused on the bigger picture. Ideally you are given authority to implement within the approved principles. But even if you have to go back with a detailed plan, once the committee has approved the outcome and the principles to be followed it is much harder for them to reject a solution that sticks to those, let alone to kill the project.

Looking at the wider world, perhaps the Ten Commandments of the Bible provide a good example of this approach. For a more business-relevant example, see my earlier posts on the principles behind good internal governance.

More generally, defining top-level principles is also the key to delegating decision-making to local managers. It means that they can make decisions which take proper account of local conditions, while ensuring that decisions made by different managers in different areas all have an underlying consistency.

A long time ago, I proposed an important change to a committee of senior colleagues. The overall intent was hardly arguable, and I had carefully thought out the details. Overall, it got a good hearing. But then the trouble started. One manager picked on a point of detail which he didn’t like. OK, I thought, I can find a way round that. But then other managers piled in, some supporting my position on that, but objecting to different details. The discussion descended into a squabble about detailed points on which no-one could agree, and as a result the whole project was shelved despite its overall merits.

I learnt an important lesson from that experience. When a collective decision is required, detail is your enemy. Most projects will have – or at least may be perceived to have – some negative impacts on some people, even though overall they benefit everyone. Maybe someone loses autonomy in some area, or needs to loan some staff. Maybe there is some overlap with a pet project of their own. Whatever the reason, providing detail at the outset makes those losses visible, and can lead to opposition based on self-interest (even if that is well-concealed) which kills the whole project. As we all know, you can’t negotiate with a committee.

So what is the answer? The approach I have found works best is to start by seeking agreement for general principles with which the implementation must be consistent. The absence of detail means that the eventual impacts on individual colleagues are uncertain, and consequently the discussion is more likely to stay focused on the bigger picture. Ideally you are given authority to implement within the approved principles. But even if you have to go back with a detailed plan, once the committee has approved the outcome and the principles to be followed it is much harder for them to reject a solution that sticks to those, let alone to kill the project.

Looking at the wider world, perhaps the Ten Commandments of the Bible provide a good example of this approach. For a more business-relevant example, see my earlier posts on the principles behind good internal governance.

More generally, defining top-level principles is also the key to delegating decision-making to local managers. It means that they can make decisions which take proper account of local conditions, while ensuring that decisions made by different managers in different areas all have an underlying consistency.I once worked for a young organisation with big ambitions. The managers were all highly experienced, but had only recently come together as a team. They decided to contract with a long-established and very stable international firm to help with operations.

I don’t think anybody was expecting what happened next. The partner firm arrived, and immediately started to call the shots. Needless to say, hackles rose amongst my colleagues – we were the customer, after all: isn’t the customer always right? It took some considerable (and uncomfortable) time to make the relationships work.

What happened? This was all about organisational maturity. The partner organisation had well-established ways of doing things and strong internal relationships. Everyone knew what they were there to do, and how it related to everyone else. They knew that their colleagues could be trusted to do what they expected, and to back them up when necessary. That organisational maturity gave them a high degree of confidence.

My organisation, on the other hand, had none of that. Although individuals (as individuals) were highly competent and confident, there had not been time for strong relationships to develop between us. Although there would be an expectation of support from others, without having been there before certainty about its strength, timeliness and content was lacking. In those circumstances, collective confidence cannot be high. Eventually our differences were sorted out, but it might have been quicker and easier if the relative lack of organisational maturity and its consequences had been recognised at the start.

Confidence comes not just from the confidence of individuals. It is also about the strength of teamwork, and a team has to work together for some time to develop that trust and mutual confidence. When two organisations interact, expect their relative maturities to affect the outcome.

Many years ago I used to make pottery as a hobby. After a few years I got to be good enough that friends sometimes asked me to make pots for them. Of course, that is when things start to get a bit difficult – what to charge them? I could have said “I’m a hobby potter – if I cover my costs, that will be fine.” But then, if a friend asked me to make something (in principle at least) it was instead of buying from someone who was trying (and mostly struggling) to make a living out of potting. For someone like me to undercut them seemed wrong. I always charged about what I thought they would have had to pay a ‘real’ potter for something similar. That way I felt that they were choosing my work just because they liked what I made. When I explained, everyone thought that was fair.

Over the years, I have learnt just how important it is to value yourself appropriately. I once took a job at a rather lower salary than I had been used to, rather than continue the uncertainty of searching until I found a better one. I discovered that because I had accepted that valuation of myself, understandably everyone else did too. The job didn’t challenge me, so I got bored, but it seemed to be impossible to persuade anyone within the organisation that I could be adding more value if only they would ask me to work on some more difficult problems – of which there were plenty. The job I was doing needed to be done. Before long, I left to go to a job at a more appropriate level.

This can be a difficult balance for an interim manager. Price is only an imperfect proxy for the value of the job, but what a customer expects to pay is usually a good indication of how they see it. We all need to pay the bills, but accepting a disparity in price perceptions is not usually a good basis for a satisfying relationship in any kind of transaction.

Many years ago I used to make pottery as a hobby. After a few years I got to be good enough that friends sometimes asked me to make pots for them. Of course, that is when things start to get a bit difficult – what to charge them? I could have said “I’m a hobby potter – if I cover my costs, that will be fine.” But then, if a friend asked me to make something (in principle at least) it was instead of buying from someone who was trying (and mostly struggling) to make a living out of potting. For someone like me to undercut them seemed wrong. I always charged about what I thought they would have had to pay a ‘real’ potter for something similar. That way I felt that they were choosing my work just because they liked what I made. When I explained, everyone thought that was fair.

Over the years, I have learnt just how important it is to value yourself appropriately. I once took a job at a rather lower salary than I had been used to, rather than continue the uncertainty of searching until I found a better one. I discovered that because I had accepted that valuation of myself, understandably everyone else did too. The job didn’t challenge me, so I got bored, but it seemed to be impossible to persuade anyone within the organisation that I could be adding more value if only they would ask me to work on some more difficult problems – of which there were plenty. The job I was doing needed to be done. Before long, I left to go to a job at a more appropriate level.

This can be a difficult balance for an interim manager. Price is only an imperfect proxy for the value of the job, but what a customer expects to pay is usually a good indication of how they see it. We all need to pay the bills, but accepting a disparity in price perceptions is not usually a good basis for a satisfying relationship in any kind of transaction.

There you are, head down in a report, a spreadsheet, or some other urgent bit of business. There’s a knock, and your mind returns to your desk from miles away. Someone says they have a problem and can they talk it over with you please? An interruption. What are you going to say?

Your work is high-value, it takes real concentration, and you need to keep your focus to get it done right. On the other hand, if you send them away, you may be telling them that you do not value them and what they do.

Of course my own work seems urgent, but I know I’ll get it done one way or another. My colleague on the other hand is important, because it is essential for the longer term that they feel valued. I could easily – and quickly – damage a relationship I have taken a long time to build. I know they would not interrupt me when I’m busy unless they felt it was important. It is really important to give them something to show that I’m taking them seriously.

Even if I decide I can only spare 5 minutes now, I’ll always offer that as a first step, at least to give them things to be thinking about until I can pay full attention. If I give them proper respect, value them, take their problems seriously, I find that they respect me back – and interruption is rare unless it really is necessary.

So if you really can't deal with the interruption fully there and then, at least find some compromise. It will pay you back in the long run.

There you are, head down in a report, a spreadsheet, or some other urgent bit of business. There’s a knock, and your mind returns to your desk from miles away. Someone says they have a problem and can they talk it over with you please? An interruption. What are you going to say?

Your work is high-value, it takes real concentration, and you need to keep your focus to get it done right. On the other hand, if you send them away, you may be telling them that you do not value them and what they do.

Of course my own work seems urgent, but I know I’ll get it done one way or another. My colleague on the other hand is important, because it is essential for the longer term that they feel valued. I could easily – and quickly – damage a relationship I have taken a long time to build. I know they would not interrupt me when I’m busy unless they felt it was important. It is really important to give them something to show that I’m taking them seriously.

Even if I decide I can only spare 5 minutes now, I’ll always offer that as a first step, at least to give them things to be thinking about until I can pay full attention. If I give them proper respect, value them, take their problems seriously, I find that they respect me back – and interruption is rare unless it really is necessary.

So if you really can't deal with the interruption fully there and then, at least find some compromise. It will pay you back in the long run. Many years ago, I was given a piece of advice by a sales manager colleague which has stuck with me ever since: “God gave you two ears and one mouth. Use them in those proportions!”

This is not just about sales in the formal sense. Whenever we are trying to influence people for any kind of outcome – and let’s face it, that is most of the time – we should remember it.

Where does influence come from? To gain influence, first we need to be trusted. People need to believe that we are behaving with integrity, that we have their interests in mind, not just our own. Naturally it is best if that is actually true. Second, we need to be respected (in fact, ‘respect for’ is almost shorthand for ‘willing to be influenced by’). Much of respect comes from a perception that we speak with authority, which presupposes trust in what we say.

How do we establish trust? That is where the ears come in. Sadly, the experience of many people in many organisations is that managers never find the time to listen to them properly. Even if you are sitting in front of him or her, it may be clear that the manager’s mind is only half on the conversation you are trying to have. How can you know what matters to someone if you don’t listen when they tell you? If you don’t know, how can you be trusted to look after them? Those ears are very powerful!

As a change manager, listening is a particularly powerful tool. It is a truism that most people dislike change, but I believe that much of that is about feeling they have no voice in it. Even when people come into a meeting feeling angry about a change that is being imposed on them, it always amazes me how much more acceptance can be achieved simply by spending time really listening to them tell you what they don’t like – even if you can’t alter it. Good listening involves the mouth as well: how do they know you heard them if you don’t play it back?

Once you have listened and built some trust, you are in a position to build respect too: by explaining the changes in a way that relates to their concerns but is anchored in reason. They will still need to move through the change curve, but by using your ears and your mouth in the right ways and the right proportions you can make that easier for everyone.

Many years ago, I was given a piece of advice by a sales manager colleague which has stuck with me ever since: “God gave you two ears and one mouth. Use them in those proportions!”

This is not just about sales in the formal sense. Whenever we are trying to influence people for any kind of outcome – and let’s face it, that is most of the time – we should remember it.

Where does influence come from? To gain influence, first we need to be trusted. People need to believe that we are behaving with integrity, that we have their interests in mind, not just our own. Naturally it is best if that is actually true. Second, we need to be respected (in fact, ‘respect for’ is almost shorthand for ‘willing to be influenced by’). Much of respect comes from a perception that we speak with authority, which presupposes trust in what we say.

How do we establish trust? That is where the ears come in. Sadly, the experience of many people in many organisations is that managers never find the time to listen to them properly. Even if you are sitting in front of him or her, it may be clear that the manager’s mind is only half on the conversation you are trying to have. How can you know what matters to someone if you don’t listen when they tell you? If you don’t know, how can you be trusted to look after them? Those ears are very powerful!

As a change manager, listening is a particularly powerful tool. It is a truism that most people dislike change, but I believe that much of that is about feeling they have no voice in it. Even when people come into a meeting feeling angry about a change that is being imposed on them, it always amazes me how much more acceptance can be achieved simply by spending time really listening to them tell you what they don’t like – even if you can’t alter it. Good listening involves the mouth as well: how do they know you heard them if you don’t play it back?

Once you have listened and built some trust, you are in a position to build respect too: by explaining the changes in a way that relates to their concerns but is anchored in reason. They will still need to move through the change curve, but by using your ears and your mouth in the right ways and the right proportions you can make that easier for everyone. I have been reading

I have been reading