This is article 6 in my series on designing internal governance.

You have decided on your meeting structure, what each meeting is for and how much authority it has. This article is about choosing members of internal governance meetings.

Cabinet Responsibility

A good place to start this discussion is with Government, and the concept of Cabinet Responsibility. On most matters, however hard the arguments behind closed doors, and whatever their personal views, Cabinet members are expected to support the decisions made – or to resign if they cannot. They are party to making those decisions, and they must own the outcome. Collective Accountability in governance is a similar concept. But in choosing members of internal governance meetings, we have to remember what we are trying to achieve. What happens when you fail to involve people in making decisions that will affect them? I’ve seen a variety of reactions, but what you can’t expect is that it will make no difference. Put yourself in that situation: how do you react? Initially the person will probably be angry, although not necessarily openly so. If nothing is done to put things right, at the very least they will give you less commitment; it is quite possible that they will feel an impulse to allow (or even encourage) things to go wrong, to prove their point, and not all of them will successfully resist it. At the other extreme, I was recently at a meeting attended by 35 people, of whom I think 8 spoke. Was there really 27 hours-worth of value from the rest attending? I doubt that that sort of attendance does anything for ownership, anyway. Large meetings not only waste time, they tend to encourage grandstanding, and inhibit the full and frank discussions which may be necessary, but which are better not held in front of a large audience. Being a member of the meeting can be seen as a matter of status, so there is also a need to separate genuine needs for inclusion from status-based ones.Choosing members of internal governance meetings: inclusivity versus efficiency

Deciding membership of Collective Authority bodies requires balancing the desire for inclusivity (more people) with the need for the body to be efficient (fewer people). Remember why we use collective authority: to ensure that decisions are owned by all those who need to own them. Identify who that will be, given the Terms of Reference expected, and choose members accordingly, remembering to check that the resulting membership is also appropriate for the level of delegated authority to be granted. It is likely that this will mean that most members are of a similar level in the organisation; this is in any case usually required for effective debates. Where necessary, specialists or team members may attend meetings to provide knowledge of detail. However, this does not mean that they need be members, nor that they count towards the quorum – nor that they can come next time! They should generally only attend for the item that they are supporting. Create the right expectation at the start: it is hard to send people out if a pattern of not doing so has developed. Normally the Chair of a “parent” meeting will not be a member of subsidiary meetings (remember that in a hierarchy, every meeting has one and only one parent meeting from which they receive their authority!), but if, exceptionally, they are, there may be an expectation that as (probably) the most senior person present, they should chair that meeting also. This is not helpful for clarity, as it results in the difference in authority levels between the meetings being less clear. If they are there, it should be because they have expertise which is required, not because of their seniority. If a subsidiary meeting’s membership looks almost the same as the membership of its parent meeting, it is worth considering whether they are really different meetings, or whether the matters to be considered should simply be reserved at the higher level. If not, then the membership should be slimmed down.Principles to establish:

- That the list of staff (or roles) to be included as members in the Collective Authority arrangements will balance the need for ownership of decisions with minimum meeting membership

- That clear rules for meeting attendance will be agreed and maintained

This is article 5 in a series about designing internal governance.

I once worked in an organisation which needed to procure many large construction projects. Nearly all of these were subject to European Union procurement rules, which make specific steps in the procurement processes mandatory, and which create some short deadlines despite lasting months overall. It’s a bit like a game of Snakes and Ladders (but without the ladders): if things go wrong you may have to start all over again. Consequently, inability to control the processes well is a serious risk. This article is about how to get delegation and escalation right.

Unfortunately, the general level of authority delegated to the local Board was a fraction of the contract value for most of the procurements, meaning that awarding these contracts needed the approval of the main Board. They normally met only about every 2 months, and had little knowledge of the issues. Control of that process was out of our hands. Very careful planning (and significant extra work) was required to minimise the risk of failing to get properly-authorised approvals at the necessary times, and so avoid the ‘snakes’.

Fortunately, once we were able to demonstrate that we had well-managed internal governance, more appropriate delegations were granted. Nevertheless, the example illustrates the problems that can arise when the level of delegations is not appropriate to the required decisions.

Note that it is normal for Boards to have ‘Reserved Matters’ which are not delegated at all; the same principle will apply at lower levels as well. Just because there is a box on the authority grid does not mean it has to be filled!

Principles to establish:

Delegation and escalation levels: getting the balance right

Deciding what authority to delegate requires balancing the need for control with the need for practical delivery, which includes the need for timely decisions. The place to start is the levels of authority to be delegated. What will meet the business need, taking account of the volume of decisions are required, and which it is practical to make in the time available at different levels? The membership of the bodies to which delegation is made then follows: it should be chosen to ensure that the members have the competence they will need. If you start with the membership, and then decide what decisions they can be trusted with, the result may not deliver what the business needs. A delegated authority generally consist of two parts: a subject and a value or scale limit. The subjects will probably be the same at different levels in the hierarchy, but the scale limits will vary. A decision which exceeds the limit at one level must be escalated up the structure, perhaps with a transition from Individual to Collective Authority part way up. It is convenient to articulate both the subjects and the authority limits in an authority grid or scheme of delegations. Obviously there will normally be one or more columns for financial and budget matters. A programme organisation might also require columns such as changes to delivery time, changes to scope and requirements, and quality assurance (see example grid below). Obviously, other kinds of organisations will have other requirements. How will you decide what the authority levels should be? This is another question of balance, this time between the desire to encourage ownership and accountability at lower levels, and the need to retain senior accountability for the bigger decisions. While this can never be a precise science, limits should generally be set so that the proportion of all the decisions which come to a body (or indeed an individual) and which must be escalated to a higher level is expected to be fairly small – perhaps 10-20%. This pattern, repeated at each level and interpreted intelligently, ensures that the Board (and each level below it) sees what it needs to see, without being overwhelmed by volume or delaying decisions unnecessarily. Equally importantly, each lower level feels it has the trust of its superiors and is empowered to do its job.Authority grid

While setting such limits for financial decisions is straightforward because the escalation levels are easily quantified, it is not quite so simple (although just as important) in other areas. However, in these cases practical qualitative tests can work perfectly well. The illustrative authority grid shown includes examples of tests which are still sufficiently objective to be useful.| Category | Requirements | Financial/Budget | Time | Quality | Control |

| Level A | Set overall strategic direction | Budget including contingency Larger budget changes | Approve third line assurance | Appoint Level B Cancel a programme | |

| Level B | Approve programme scope & requirements Approve changes to scope & requirements | Change allocations within portfolio contingency | Changes which delay benefits delivery | Approve second line assurance, commission third line assurance | Appoint Level C Initiate programme and approve business case Close programme on completion |

| Level C | Approve design and outputs as meeting requirements Approve design or output changes which meet requirements | Change allocations within programme contingency | Changes with no impact on benefit delivery | Approve first line assurance, provide/ commission second line assurance | Appoint Level D Options selection Approve stage gates, output acceptance & readiness to proceed Accept key milestone completion |

| Level D | Change allocations within project contingency | Changes with no impact on key milestones | Commission first line assurance | Accept project milestone completion |

- That the authority grid should include qualitative as well as quantitative delegation limits, and should not be restricted to areas where a financial limit can be set

- That escalation levels will be set to provide an appropriate level of filtering, decided on the basis of business need and practical delivery

- That decisions about committee membership should be made in the light of the delegation levels set

This is article 4 in my series on designing internal governance.

Some while ago, I was asked to map part of the internal decision-making structure (below Board level) in an organisation I was working in. I talked to the people involved, asking where decisions came to them from, and where they were passed on to, and followed the chain. That exercise taught me a lot about hierarchy in internal governance!

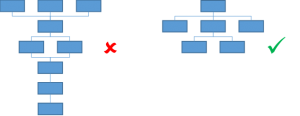

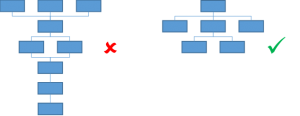

The overall picture that emerged was not very clear, which was not a good start (no surprise that everyone else was confused!). However, there were some things that I could say for certain. There were at least six layers: that sounds like a lot of people, a lot of time, and almost certainly a lot of delay, in making decisions. In the middle of the escalation route, there appeared to be a loop: at that level, there were two possible places for the next decision to get made. I still don’t know why, or how you would decide which side of the loop to go round, or what the body not consulted would have thought. And finally – worst of all – if you had to go all the way up the chain, there were three separate bodies at the top! I have no idea how any conflict would have been resolved. I don’t believe that the structure had been deliberately set up like that – it had just evolved. Needless to say, the organisation no longer exists.

Hierarchy in internal governance: What does good look like?

What would a good structure look like? Good governance requires a simple (upside-down) tree structure. As you go up, several branches may join together, but no branch ever divides. Everything comes together at one body (the Board, reporting to shareholders) at the top. A fundamental point that is sometimes forgotten is that no governance body can be free-standing: if it is not part of the hierarchy it is not part of governance! In deciding what governance bodies we need and how they should relate to each other, we need to find the right balance between, on the one hand, simplicity and clarity of the structure, and, on the other, efficiency and effectiveness in decision-making. Governance only works well if everyone understands it. A simple structure with very few ‘branches’ is simple and easy to understand, but can overload the small number of decisions makers, and may not be very inclusive. On the other hand, a greater number of more specialised meetings, while more ‘expert’ and perhaps more efficient for decision making, will add complexity, reduce clarity, be less joined-up, and be harder to service. So where do we start? All authority within an organisation initially rests with its Board. It then makes specific delegations of that authority. The authority it delegates in turn rests where it is delegated, unless it is specifically sub-delegated by that body. The authority to sub-delegate should be specifically stated (or withheld) in the Terms of Reference; by definition, the lowest tier of Collective Authority bodies cannot have this authority. A body may only delegate authority which it holds itself, and then only if it also has been given the specific authority to do so. These rules naturally create a simple tree structure as described above. The decisions to be made in setting up the structure are- How many levels does it need?

- What is the best way to group the delegated decisions within a level?

Principles to establish:

- That the governance structure will be strictly hierarchical, and that all bodies which have Collective Authority will have a place within that hierarchy;

- That the design will proceed by establishing those areas where the Board should make delegations (starting by noting the matters already reserved to the Board), and how they should be grouped

- What (if any) dual-key arrangements are desirable?

This is article 3 in my series on designing internal governance.

One of the most stressful times I can remember in my career as a manager resulted from lack of clarity about authority. I had a big job, and it was reasonably clear what I was accountable for delivering. A few days in, I asked my boss to clarify what authority I had to make decisions. His answer? “I don’t like talking about authority.” I never did get more clarity, and it became clear that whatever authority I did have, it was not commensurate with my accountabilities. This article is about authority and accountability in internal governance.

Authority and Accountability

Matching authority and accountability is a key requirement in any governance structure. If you give someone accountability but not authority, you also give them perfect excuses for failing to deliver (and so in practice for not being accountable): for example, “well, if you had listened to me when I said that was too novel, it would all have been fine.” At best, it results in delays and frustration while decisions are referred. Similarly, if you give someone authority but not accountability, they can make extravagant promises about what will be delivered, and lay the blame for the resulting failure on the person accountable. The blame for the failure really lies with the person who set things up like that in the first place. At the opposite extreme is giving too much authority to the accountable person. This is the case where there is no external holding to account. Very few organisations these days would allow even the CEO to approve their own expenses. But other similar situations are sometimes found, for example, a Programme Director chairing his own Programme Board. While most of the time the situation is probably not abused, it does nothing to remove the temptation to approve a pet project regardless of the business case, or to hide bad news in the hope that things will improve later. It is much wiser to avoid setting up conflicts of interest in the first place than to hope that everyone will be able to resist the temptation to benefit from them. These examples show that deciding what authority to delegate requires balancing the need for control with the need for practical delivery, which includes the ability to hold people to account effectively. Deciding to whom to delegate it brings in a new problem: it requires balancing the desire for decisions to be owned by all those affected directly by the consequences with the desire for a named person who can be held to account. Suppose we need to let a major contract. Perhaps an operations team will have all the day-to-day interactions with the contractor, and they are convinced that Contractor A is going to be best to work with. Should the Operations Director have the final say? At least then we know who to blame if it goes wrong. But the Procurement Director may know that the contractor’s resources are going to be very stretched if they take on this work. The Commercial Director may not be happy with the terms of the contract that can be negotiated. The Finance Director may not be happy with the performance bonds or guarantees they can offer. How do we make the best decision?Collective and Individual Authority

At this point we need to recognise that there are two sorts of authority: Individual and Collective. Collective Authority means that the decisions are made by a specified group of people; no individual has the authority to make those decisions on their own (hence the need for a quorum to be specified in the Terms of Reference (ToRs) for the group). The group must be established by the delegating body – no decision-making body has authority to create itself (or appoint its members, or approve its ToRs)! Individual Authority means that the decisions are made by one individual, even if that individual appoints a group of people to advise him/her. An advisory group can of course always be set up by the individual holding the authority; it is not part of the governance structure, having no authority, so it does not need terms of reference (it just does whatever the decision maker asks of it), and a quorum would be meaningless. That does not stop the members of such a group being confused about its solely advisory nature if this is not explained. Designing the governance structure requires deciding what to use where, but how do you decide which sort of authority is appropriate? The choice between Collective and Individual Authority must balance the possible need for wide ownership of and support for decisions against the preference for Individual accountability which goes with Individual authority. Generally Collective Authority will be desirable at the most senior levels and for the most complex decisions, where the best outcome will result from contributions from people with different backgrounds, knowledge and experience, or where it is important that several people at the same level, typically across functions, feel they are committed to the decision because they helped to make it. Many (perhaps most) of the strategic decisions the company needs to make will be of this kind. On the other hand, Individual Authority will be preferred where the issues are more focused, and typically fall clearly within one functional area rather than spanning several. This kind of authority is just what line management structures are about. It is normally granted through Letters of Appointment and Schemes of Delegation. We will have little more to say about it here. The further down the governance structure you go, the less the diversity that Collective Authority brings to decision making is likely to be needed, and the more likely it is that line management provides all the ownership that is needed. At the same time, each additional layer of Collective Authority tends to make accountability more diffuse, which is unhelpful. Consequently, one or two layers of Collective Authority below the Board is the most that would normally be appropriate. As a general rule, the lower the level of a Collective Authority body, the fewer different interests need to be represented, so the fewer members it will need to have.Principles to establish before starting design:

- That authority and accountability must go together

- That no-one will have authority to ‘mark their own homework’ (that conflicts of interest will be avoided)

- That Collective and Individual Authority are different; and what their respective roles and interfaces will be in the structure you will create.

We all like to feel we are in control, don’t we? Especially when we have been told that there will be consequences according to how well we deliver the task we have agreed to do. We feel pretty confident in our own ability to do the job – probably we would not have agreed to take it on otherwise – but what if we can’t do it on our own? I remember the first time I had to promise to deliver something knowing that I would have to rely on other people to do substantial parts of it. While I still felt the confidence of youth that it would all work out, I also remember the frustration and discomfort of finding my instructions were misunderstood or ignored; of having to let someone else try, and sometimes fail; of not being able to control all the details. As managers, we all find our own ways to deal with this; at the company level, we need to be a bit more formal. This article is about where to start to build internal governance to address this need.

It all starts with the Board

The Board is accountable to the shareholders for delivery of the objectives of the company (public sector and non-profit organisations will have equivalent arrangements even if they are called something different). However, unless the company is very small, the Board does not have the capacity to do more than make a very small proportion of the decisions required to achieve this. It needs to retain enough control to monitor and steer the delivery of the objectives, but it must delegate the authority to make other decisions. Internal governance is the framework that it sets up to manage this. Its objectives may include the following:- To balance the Board’s need for control and assurance of delivery with its practical need to deliver through others, in a way which optimises the balance between the risks it takes by more delegation, and the costs (financial and otherwise) it imposes through more control;

- To have a secure underlying logic so that the framework is self-consistent;

- To ensure that conflicts of interest are avoided as far as possible for those with delegated authority, as these tempt people to behave in ways that are not in the best interests of the organisation;

- To make sure that those people who will have to live with the consequences of decisions made feel ownership because they have been involved in making them;

- To ensure that decisions are escalated when, only when, and only to the level necessary for them to be made effectively, so that interventions are appropriate and timely;

- To ensure that everyone in the organisation has clarity about the decisions they can make, about where to go for those that they can’t, and about decisions made by others which affect them;

- To ensure that stakeholders have enough visibility of the decisions of the organisation to have confidence and trust in its management;

- To ensure that the governance structure is scaleable and adaptable (within reason) to allow for possible requirements for future change without major re-design.

Build internal governance

So where do you start? First, you need to remember that governance necessarily works top-down. The owners of what you design will be the Board members (or equivalent), and they are likely to have strong opinions – that’s almost synonymous with being a Board member! If you start your design at the bottom and work upwards, there is a high probability that some or all of the members will object to at least some aspects of it once they see how it will affect them. Trying to make modest changes to accommodate their concerns will probably undermine the essential integrity of the system, resulting in you having to start again. If bottom-up does not work, what does? The best place to start is to agree the main design principles with the Board members, before even beginning on the design itself. It is much harder for people to object if you can demonstrate that your design is consistent with the principles that they all agreed earlier, and it is much easier to keep the discussion rational when the specific outcomes are yet to be defined. It also helps to ensure that the whole design is self-consistent. It is also worth noting at this point that because governance exists to define flows of authority and accountability that need to run seamlessly from top to bottom of the organisation, a governance design project should take a joined-up top to bottom view too. A project that looks only at the top (or bottom) end is likely to require compromises which will reduce its effectiveness. The next few articles will discuss the principles which you will need to agree at the outset, under the headings listed below. Remember that governance is about finding the optimum checks and balances for your organisation. Because that depends on context, it will be different for every organisation. The way you express the logic and the principles in your own project needs to be right for your context. One size does not fit all!- Authority

- Hierarchy

- Escalation

- Ownership

- Documentation and language

What is governance for?

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if whenever you asked someone to do something, they just did it? And of course, on the other hand, that they didn’t do things which they had not been asked to do? Oh for perfect control! But wait a moment. Midas asked that everything he touched should turn to gold – and look where that got him. Perhaps we had better be careful what we wish for. How often have you said “No, that’s not what I meant!”? Or “I’d have thought it was obvious that that needed doing!”? Let’s face it, most of us are not that great at giving really good instructions about what we need, and we certainly don’t have time to include every detail. At the same time, the people we ask are intelligent and creative. We get better outcomes, and they enjoy the work more and so are more motivated, when we expect them to use those abilities to interpret our needs sensibly and come up with the best solutions, even when we didn’t think to ask. In summary, then, we have specific outcomes we require, but it is neither practical nor desirable for us to be completely prescriptive about how they should be delivered. Governance provides a framework within which the desires for control of outcomes and for flexibility over means can be reconciled with the minimum of effort. Such a framework is fundamentally about good behaviours. Most of us want to behave well, but doing things the way we know would be best often takes more time and effort (at least in the short term), and time is one thing that is always in short supply. Formal governance arrangements help to stop us taking the short cuts which may be unhelpful in the long run. They ensure that we communicate what we are doing – so that changes can be made if required – and may force us to plan a bit further ahead. Being able to see good governance in place reassures stakeholders that the organisation is behaving transparently. It gives Government bodies and Regulators confidence that the organisation is complying with legislation and other requirements. And it allows Boards and managers to delegate authority while retaining sufficient control. Good governance means that we not only behave honestly and competently, but are seen to be doing so, which builds trust. In short, it is the rock on which a well-managed organisation is built. What good governance is NOT about is bureaucracy, box-ticking and delays. It requires finding balances – between control and practical delivery; between the risks of delegation and the cost of control; between wide ownership of decisions and strong accountability for them; between a simple structure and efficient decision-making; between minimum overhead and an effective audit trail – which provide the optimum basis for success. Every organisation has different arrangements because the optimum trade-offs depend on the context. This is the first of a series of articles will set out the main issues to be considered in designing an internal governance system and the principles which should underlie it.I’ve just been asked by some consultants I’m working with to give feedback for their annual appraisals. As usual there is a standard set of questions they need addressed – and one of them is about leadership. That seems a tough ask for someone junior who has only started recently, and set me thinking about how I could help them. Here’s what I said.

Leadership is different for every individual. Everyone has their own personality, and so everyone has to do it in their own way. Why? It’s very simple.

Leadership means that people are willing to follow you, and for that to happen, two things are necessary: people must trust you, and you must have something to say.

Trust comes when you behave with integrity. Everything you do is consistent, both with your values and with your personality, so people have confidence about outcomes. You are ‘authentic’. Everyone has their own personality, so everyone’s leadership is different. If you try to lead the way someone else does, you are inevitably trying to be consistent with their personality and not with your own. Even if you can do it, you will feel uncomfortable. You will come over as not authentic, and you won’t be fully trusted. As Oscar Wilde said, “Be yourself; everyone else is already taken!”

Leadership is for everyone

Everyone has something to say. We all have unique experiences starting from our earliest days, and it is human nature to use the stories of our past experiences to help us decide how to deal with new situations. Everyone has insights they can contribute, although of course the more experience you have the more you have to offer. If everyone can do these two things, leadership is not just for Leaders with a capital L. Leadership is about having the confidence to be yourself, and to share whatever your experience tells you about the situation you are in. Followers will follow!Near where I live, there is a wonderful cheese shop. It sells an amazing selection of English artisanal cheeses, as well as a variety of other delicious local produce. Not surprisingly, it is my place of choice for cheese for Christmas. It's just a pity that the customer service is not up to the standard of the cheese.

I placed my order in good time, for collection on 23 December. I duly arrived at the shop, full of anticipation, on my way home from work. The table outside groaned with goodies including beautifully-decorated cakes, rustic breads and colourful preserves. The shop is fairly simple inside, but filled with the wonderful aroma from the cheeses and from the delicious food being served in their upstairs café.

There seemed only to be one young lady serving, and she looked a bit stressed by the queue of customers; cutting, weighing and wrapping cheeses is a slow process. Still, I assumed serving me would be easy – all that should have been done already. She looked in the fridges under the cool counter; not there. She looked in another fridge; no better. Looking more stressed, she told me that she was very sorry, she couldn’t find my order; “Would you mind going away and coming back later?”

Bad move. “Yes, actually, I would. I’m on my way home from work, I've had a busy day, and I don’t want to hang around. That’s why I placed an order.” Another hunt still produced nothing.

A small lady with shoulder-length reddish hair came in – the manager. We found where my order had been written in the book, just as I had said. “Well, if you can wait, we can make up some of your order again, but I’m afraid we have none of the Tamworth left. We are completely sold out of soft cheeses.” I grumpily agreed that they had better do that, meanwhile starting to wonder where I would be able to find a good soft cheese on Christmas Eve. Then she showed me a small cheese –under 100g I would say – and said “we have one of these left. They are absolutely delicious – unfortunately I can’t give you a taste as it is the last one. They are £6.” … So that is about £60 / kg? Are you serious? No thanks.

After that, the manager lost interest. The assistant worked out the total price, and only then said “we’ll give you 10% off for the inconvenience”. I paid, and walked out with my cheese, about 20 minutes later than I had expected and in a thoroughly bad temper.

So what did I learn from these unhappy events? Observing my own feelings, first, that the longer the problem lasts, the more it takes to put it right. And second, that if you don’t do enough, you might as well do nothing.

Good customer service

The first rule of customer service is “keep your promises”. And since things will sometimes go wrong, the second rule is “When you can’t keep your promises, try to solve the problem you have caused as quickly as you can”. If the assistant had said at the start something like, “I’m really sorry, I’ll make the order up as quickly as I can. You can have a free coffee upstairs while you are waiting. What can I offer you instead of the Tamworth?” – suggesting solutions to my problems – I would probably have been satisfied, and would actually have spent more. By the time the manager showed me the expensive cheese, she needed to have given it to me, not offered to sell it to me, to compensate. And by the end, a 10% discount not only did not solve my problem but felt like adding insult to injury. A customer problem is an opportunity for free good – or bad – publicity. The choice of which is yours. [contact-form][contact-field label='Name' type='name' required='1'/][contact-field label='Email' type='email' required='1'/][contact-field label='Website' type='url'/][contact-field label='Comment' type='textarea' required='1'/][/contact-form] Walking along Blackfriars Road in London the other day, I realised that there was something odd about the very ordinary building I was passing. I must have walked past it quite a few times before, perhaps thinking about something else, perhaps looking the other way, perhaps just being unobservant – but this was the first time I had noticed.

How often are we so conditioned by what we expect to see that, so long as it more or less conforms to the norm, we build the oddities into our prevailing view rather than seeing things from a new perspective (curved window sills? A bit odd, maybe, but architects like to try out different ideas)? Change is difficult to implement, but the biggest problem is often getting started in the first place because people find it very hard to change the way they look at the issue, and so can’t see the need for a radical re-think. Another visual parallel is photographs of things like moon craters – do they go in or do they go out? Once you see it one way, it is hard to see it the other.

As a change agent, part of my job is to help people to see issues from a new perspective, and then to see that that new perspective leads to a new and better way of organising the response. If there is no new perspective, there is nothing to justify the change, and it is easy to see why people would choose to carry on as before.

If you still haven’t got it, look at http://www.london-se1.co.uk/news/view/7248 - or just try looking at the picture upside-down!

[contact-form][contact-field label='Name' type='name' required='1'/][contact-field label='Email' type='email' required='1'/][contact-field label='Website' type='url'/][contact-field label='Comment' type='textarea' required='1'/][/contact-form]

Walking along Blackfriars Road in London the other day, I realised that there was something odd about the very ordinary building I was passing. I must have walked past it quite a few times before, perhaps thinking about something else, perhaps looking the other way, perhaps just being unobservant – but this was the first time I had noticed.

How often are we so conditioned by what we expect to see that, so long as it more or less conforms to the norm, we build the oddities into our prevailing view rather than seeing things from a new perspective (curved window sills? A bit odd, maybe, but architects like to try out different ideas)? Change is difficult to implement, but the biggest problem is often getting started in the first place because people find it very hard to change the way they look at the issue, and so can’t see the need for a radical re-think. Another visual parallel is photographs of things like moon craters – do they go in or do they go out? Once you see it one way, it is hard to see it the other.

As a change agent, part of my job is to help people to see issues from a new perspective, and then to see that that new perspective leads to a new and better way of organising the response. If there is no new perspective, there is nothing to justify the change, and it is easy to see why people would choose to carry on as before.

If you still haven’t got it, look at http://www.london-se1.co.uk/news/view/7248 - or just try looking at the picture upside-down!

[contact-form][contact-field label='Name' type='name' required='1'/][contact-field label='Email' type='email' required='1'/][contact-field label='Website' type='url'/][contact-field label='Comment' type='textarea' required='1'/][/contact-form]Coming home from work the other day I saw a poster on the Tube which grabbed my attention. Leaving out the unnecessary details, it said

“Buy a ……, get a free …… worth £49!”

Is it really? Value, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. The company may choose to sell the gadget for £49 normally, but that certainly does not mean it is worth £49 to me. In fact, it almost certainly isn’t – it might be worth more, in which case even if I had to pay for it I would think I was getting a good deal (and I may well have already bought one anyway), or it is worth less, in which case I’d never buy one normally, but might be tempted to get one for nothing. It is pretty unlikely that they have hit on exactly the right value for me.

Our entire economic system is based on the idea that things have different values to different people. That is how trade works – if it were not like that, it would be impossible to make a profit on trading, so there would be no incentive to do so. I buy something because it is worth more to me to have the thing than the money. The seller sells it because they value having the money more than the thing. It may be in the trader’s interests to confuse value with price, but in the end we all make our own judgements about what something is worth to us.

[contact-form][contact-field label='Name' type='name' required='1'/][contact-field label='Email' type='email' required='1'/][contact-field label='Website' type='url'/][contact-field label='Comment' type='textarea' required='1'/][/contact-form]