I’ve just come back from the local parcel office with a parcel. Yesterday I had one of those cards through the letterbox that tell you that they had tried to deliver a parcel, and I could collect it from the office.

The thing is, I know that they didn’t try to deliver the parcel. I was in, and the card just came through the letterbox with the other mail. I was next to the front door at the time - no ring, no knock.

Of course I understand that a large proportion of people they have parcels for are out when they call. I can see that they are just trying to make the jobs of the delivery people more efficient. It saves them the effort of carrying all that extra weight and bringing most of it back again. It saves them waiting to see if someone answers. And it saves them having to write out cards on the doorstep, possibly with rain smudging the ink and making the card go soggy.

The thing is though, I have paid to have that parcel delivered. I knew that I was most probably going to be in when the mail came round, so I was happy to take the small risk that I wouldn’t be and that I would have to collect it. I paid them to take the risk that I wouldn’t be in, with its efficiency implications. By writing out the cards without the parcel even leaving the office, they avoided the risk I have paid them to take, and transferred the inefficiency to me. Sadly, it is not just one organisation doing this – I have had similar experiences with other delivery services.

I’ve just come back from the local parcel office with a parcel. Yesterday I had one of those cards through the letterbox that tell you that they had tried to deliver a parcel, and I could collect it from the office.

The thing is, I know that they didn’t try to deliver the parcel. I was in, and the card just came through the letterbox with the other mail. I was next to the front door at the time - no ring, no knock.

Of course I understand that a large proportion of people they have parcels for are out when they call. I can see that they are just trying to make the jobs of the delivery people more efficient. It saves them the effort of carrying all that extra weight and bringing most of it back again. It saves them waiting to see if someone answers. And it saves them having to write out cards on the doorstep, possibly with rain smudging the ink and making the card go soggy.

The thing is though, I have paid to have that parcel delivered. I knew that I was most probably going to be in when the mail came round, so I was happy to take the small risk that I wouldn’t be and that I would have to collect it. I paid them to take the risk that I wouldn’t be in, with its efficiency implications. By writing out the cards without the parcel even leaving the office, they avoided the risk I have paid them to take, and transferred the inefficiency to me. Sadly, it is not just one organisation doing this – I have had similar experiences with other delivery services.

Keep your promises

A more honest approach would be to offer two categories of delivery at two different prices: a cheaper service, where you know you will have to collect, and a more expensive one where the attempt to deliver will be made. That way you could price the risk realistically. But providing the cheaper service when the customer has paid for the more expensive one is just wrong. In most industries, you would not get away with it. I have no doubt that they are all under a lot of competitive pressure. Probably local managers have concluded that it is necessary to do this to meet the tough performance targets which result. If so, that betrays both a cavalier approach, and a lack of joined-up thinking. If you don’t give your customers what they pay for, sooner or later they stop being customers. As a professional change manager and consultant, I get asked to advise on how to bring about cultural change in organisations. Often, part of the conversation goes something like this:

“We really need to change how we do things. We just don’t have enough hours in the day to get everything done.”

“Yes, I can see that that would be a problem. I’m sure that there is a better way. It sounds like you need to delegate more. How comfortable are you with delegating to your managers?”

“That would be fine. But the problem is, our staff don’t have enough time for everything they need to do now either.”

“Hmm. You need a change programme – which you will need time and energy to lead – but you don’t have any spare capacity, and there is nowhere you can delegate stuff to free up some. So what parts of what you do now are you willing to see not being done at all to make the change happen?”

That often produces blank looks. But you have to devote time to leading change if you want it to succeed. You also have to lead by example. You have to demonstrate that change is a sufficiently high priority for you that it displaces other things. Other people are unlikely to change what they do until they see you changing what you spend time on, not just talking about doing so.

As a professional change manager and consultant, I get asked to advise on how to bring about cultural change in organisations. Often, part of the conversation goes something like this:

“We really need to change how we do things. We just don’t have enough hours in the day to get everything done.”

“Yes, I can see that that would be a problem. I’m sure that there is a better way. It sounds like you need to delegate more. How comfortable are you with delegating to your managers?”

“That would be fine. But the problem is, our staff don’t have enough time for everything they need to do now either.”

“Hmm. You need a change programme – which you will need time and energy to lead – but you don’t have any spare capacity, and there is nowhere you can delegate stuff to free up some. So what parts of what you do now are you willing to see not being done at all to make the change happen?”

That often produces blank looks. But you have to devote time to leading change if you want it to succeed. You also have to lead by example. You have to demonstrate that change is a sufficiently high priority for you that it displaces other things. Other people are unlikely to change what they do until they see you changing what you spend time on, not just talking about doing so.

Change needs time

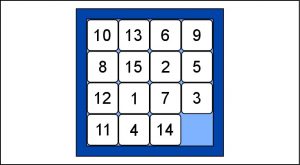

Think of it like a sliding-tile puzzle. In a 4 x 4 puzzle there are 15 tiles, so that there is always one space to move the next tile into. That gives enough flexibility to rearrange all the tiles into the right pattern. If there were 16 tiles – completely filling the frame – nothing could move at all. You have to find an empty space in your time, like the missing tile, to be able to rearrange your organisational tiles. Like many things in life, this is just about priorities. If change is high enough up your priority list, it will displace other activities to create the necessary space. If it isn’t, it is best not to start. This seasonal message will help you to remember! A few days ago I went to a concert. Not a typical one though. I was attracted by the lines “…even if you know nothing at all about…”, and “We know all people will bring intelligent ears with them.” An opportunity to experience something new.

The music was by Karlheinz Stockhausen, a pioneer of electronic music in the 1950s who had a major influence on the world of pop as well as on ‘serious’ music (he is one of the faces on the cover of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper album). It was an extraordinary evening.

Some people might not regard what we heard as music at all, but just a jumble of noises. Beforehand, I might have been one of them. What astonished me was that the whole experience was completely enthralling. The sound as you might hear it from loudspeakers at home was only one element. The virtuosic skill of the performers creating this incredibly complex sound was humbling to watch. The continually-changing spatial arrangement of the sound, and the atmosphere created by being with all those other ‘intelligent ears’ added other dimensions. Somehow, the jumble started to make sense. It was an evening to remember for a long time.

A few days ago I went to a concert. Not a typical one though. I was attracted by the lines “…even if you know nothing at all about…”, and “We know all people will bring intelligent ears with them.” An opportunity to experience something new.

The music was by Karlheinz Stockhausen, a pioneer of electronic music in the 1950s who had a major influence on the world of pop as well as on ‘serious’ music (he is one of the faces on the cover of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper album). It was an extraordinary evening.

Some people might not regard what we heard as music at all, but just a jumble of noises. Beforehand, I might have been one of them. What astonished me was that the whole experience was completely enthralling. The sound as you might hear it from loudspeakers at home was only one element. The virtuosic skill of the performers creating this incredibly complex sound was humbling to watch. The continually-changing spatial arrangement of the sound, and the atmosphere created by being with all those other ‘intelligent ears’ added other dimensions. Somehow, the jumble started to make sense. It was an evening to remember for a long time.

Its worth the risk

If you have never tried something, you can’t know what you are missing. Maybe it won’t work for you. But just as likely you will find new perspectives and insights that you could not have imagined otherwise. It is worth the risk.

Last week I attended the inaugural meeting of the Change Management Institute’s Thought Leadership Panel. Getting a group of senior practitioners together is always interesting. I’m sure that if we hadn’t all had other things to do the conversation could have gone on a long time!

I have been thinking some more about two related questions which we didn’t have time to explore very far. What makes a change manager? And why do so many senior leaders struggle to ‘get’ how change management works?

Perhaps the best starting point for thinking about what makes a change manager is to look at people who are change managers and consider how they got there. The first thing that is clear is that they come from a wide variety of different backgrounds. Indeed, many change managers have done a wide variety of different things in their careers. That was certainly true of those present last week. All of that suggests that there is no standard model. A good change leader probably takes advantage of having a wide variety of experience and examples to draw on - stories to tell, if you will. Where those experiences come from is less important.

Then there is a tension between two different kinds of approach. Change managers have to be project managers to get things done. But change is not like most projects: there is a limit to how far you can push the pace (and still have the change stick) because that depends on changing the mindsets of people affected. Thumping the table or throwing money at it hardly ever speeds that up. Successful change managers moderate the push for quick results with a sensitivity to how those people are reacting. Not all project managers can do that.

So I think you need three main ingredients for a successful change leader:

- The analytical and planning skills to manage projects;

- The people skills to listen and to influence and manage accordingly;

- Enough varied experiences to draw on to be able to tell helpful stories from similar situations.

Senior managers and change

Why do many senior managers struggle to understand the change process? They may well have the same basic skills, but the blending is usually more focused on results than on process. That is not surprising; their jobs depend on delivering results. A pure ‘results’ focus may be OK to run a stable operation. Problems are likely to arise when change is required if the process component is too limited. Delivering change successfully usually depends on the senior managers as well as the change manager understanding that difference. The other day I passed a set of temporary traffic lights. Hardly an unusual occurrence in a modern city! This was a nice modern set, with the lights made up of an array of LEDs. That is of course a great improvement. Apart from the environmental benefits of being low-energy and long-lasting, the light area is evenly bright all over. And there can be no problem with low sun reflecting off the back mirror so it is hard to tell which colour is illuminated.

What struck me, however, was that the LEDs were carefully arranged in a circular pattern, mimicking the traditional look of traffic lights. This is clearly not the most efficient way of arranging them. That would be a hexagonal pattern, but of course you cannot produce what looks like a neat circular outline that way.

There is no reason why in an LED system each colour of light has to be round. They could just as well be hexagonal, or any other convenient shape. A hexagon would clearly match a hexagonal pattern better. Indeed, there could be advantage in making each colour a different shape, to help the colour-blind. They make the lights round because that is how we expect traffic lights to look.

The other day I passed a set of temporary traffic lights. Hardly an unusual occurrence in a modern city! This was a nice modern set, with the lights made up of an array of LEDs. That is of course a great improvement. Apart from the environmental benefits of being low-energy and long-lasting, the light area is evenly bright all over. And there can be no problem with low sun reflecting off the back mirror so it is hard to tell which colour is illuminated.

What struck me, however, was that the LEDs were carefully arranged in a circular pattern, mimicking the traditional look of traffic lights. This is clearly not the most efficient way of arranging them. That would be a hexagonal pattern, but of course you cannot produce what looks like a neat circular outline that way.

There is no reason why in an LED system each colour of light has to be round. They could just as well be hexagonal, or any other convenient shape. A hexagon would clearly match a hexagonal pattern better. Indeed, there could be advantage in making each colour a different shape, to help the colour-blind. They make the lights round because that is how we expect traffic lights to look.

Features that get overlooked

When looking at business improvements, there are usually aspects of the status quo which we retain and aspects which we decide to change. Some features are like the colours of traffic lights. The confusion caused by changing them would a serious problem, and we know we must not. Others may be like the type of light source. It is obvious that a change is possible if it is beneficial. However, some are like the shape of lights, which we are so used to that we forget to challenge them. We always need to be on the lookout for features kept because we forgot they could be changed rather than for good reason. As an interim manager, I rely on networks to find my next assignment. Many of the people in my immediate network I have known for years, but I still make sure I keep in touch. It only needs the occasional coffee, phone call or email. With newer contacts that I know less well, I make more effort to build the relationship.

Most of those people will never give me any work. It is not that they don’t want to, but possible assignments depend on relevant needs coming up. From a hard-nosed point of view, as an investment perhaps my effort is not worth it. But I keep in touch because I want to maintain the relationships, not because they might lead to work. I believe that the willingness to meet would soon dry up if people felt I was only there to sell.

I spend quite a lot of my free time supporting my University’s alumni relations. We all know that in the end there is only one reason why universities have become so keen on keeping in touch with alumni recently. They want our money.

However, donations do not just happen. Unless there is an overt exchange (e.g. we will name xxx after you in return), persuading people to give depends on the relationship you have with them. And relationships are really between people, not between people and organisations. I build relationships with fellow alumni through activities we share only because I – and they – value the relationships themselves. If that builds engagement with the University and leads to giving, that’s good, but it is never the point. Indeed, raising the subject of fundraising at all would put some people off engaging, so it is off-limits.

As an interim manager, I rely on networks to find my next assignment. Many of the people in my immediate network I have known for years, but I still make sure I keep in touch. It only needs the occasional coffee, phone call or email. With newer contacts that I know less well, I make more effort to build the relationship.

Most of those people will never give me any work. It is not that they don’t want to, but possible assignments depend on relevant needs coming up. From a hard-nosed point of view, as an investment perhaps my effort is not worth it. But I keep in touch because I want to maintain the relationships, not because they might lead to work. I believe that the willingness to meet would soon dry up if people felt I was only there to sell.

I spend quite a lot of my free time supporting my University’s alumni relations. We all know that in the end there is only one reason why universities have become so keen on keeping in touch with alumni recently. They want our money.

However, donations do not just happen. Unless there is an overt exchange (e.g. we will name xxx after you in return), persuading people to give depends on the relationship you have with them. And relationships are really between people, not between people and organisations. I build relationships with fellow alumni through activities we share only because I – and they – value the relationships themselves. If that builds engagement with the University and leads to giving, that’s good, but it is never the point. Indeed, raising the subject of fundraising at all would put some people off engaging, so it is off-limits.

Relationship building sows seeds

The point of relationship building and maintaining networks is to create a fertile seed-bed for what you hope will germinate in the future. The gardener can dig the soil, add compost, and provide water. He can provide the conditions for successful germination. The miracle of germination though comes from the seeds themselves. I’ve just started trying to organise a local walking group for alumni from my university. The initial process was simple: I wrote an email asking for interest, the alumni office sent it out to people on their database with postcodes in the local area, and I collected the responses.

The outcome has been pleasantly surprising. The response rate was over 10%, which under almost any circumstances I would think was a fantastic return for a single ‘cold call’ message out of the blue. But almost as surprising was the proportion of responses which included words along the lines of ‘what a good idea’ with at least the implication of ‘why has no-one suggested this before?’. It seemed as if all that latent demand was just sitting there waiting to be tapped.

I’ve just started trying to organise a local walking group for alumni from my university. The initial process was simple: I wrote an email asking for interest, the alumni office sent it out to people on their database with postcodes in the local area, and I collected the responses.

The outcome has been pleasantly surprising. The response rate was over 10%, which under almost any circumstances I would think was a fantastic return for a single ‘cold call’ message out of the blue. But almost as surprising was the proportion of responses which included words along the lines of ‘what a good idea’ with at least the implication of ‘why has no-one suggested this before?’. It seemed as if all that latent demand was just sitting there waiting to be tapped.

There you are, head down in a report, a spreadsheet, or some other urgent bit of business. There’s a knock, and your mind returns to your desk from miles away. Someone says they have a problem and can they talk it over with you please? An interruption. What are you going to say?

Your work is high-value, it takes real concentration, and you need to keep your focus to get it done right. On the other hand, if you send them away, you may be telling them that you do not value them and what they do.

Of course my own work seems urgent, but I know I’ll get it done one way or another. My colleague on the other hand is important, because it is essential for the longer term that they feel valued. I could easily – and quickly – damage a relationship I have taken a long time to build. I know they would not interrupt me when I’m busy unless they felt it was important. It is really important to give them something to show that I’m taking them seriously.

Even if I decide I can only spare 5 minutes now, I’ll always offer that as a first step, at least to give them things to be thinking about until I can pay full attention. If I give them proper respect, value them, take their problems seriously, I find that they respect me back – and interruption is rare unless it really is necessary.

So if you really can't deal with the interruption fully there and then, at least find some compromise. It will pay you back in the long run.

There you are, head down in a report, a spreadsheet, or some other urgent bit of business. There’s a knock, and your mind returns to your desk from miles away. Someone says they have a problem and can they talk it over with you please? An interruption. What are you going to say?

Your work is high-value, it takes real concentration, and you need to keep your focus to get it done right. On the other hand, if you send them away, you may be telling them that you do not value them and what they do.

Of course my own work seems urgent, but I know I’ll get it done one way or another. My colleague on the other hand is important, because it is essential for the longer term that they feel valued. I could easily – and quickly – damage a relationship I have taken a long time to build. I know they would not interrupt me when I’m busy unless they felt it was important. It is really important to give them something to show that I’m taking them seriously.

Even if I decide I can only spare 5 minutes now, I’ll always offer that as a first step, at least to give them things to be thinking about until I can pay full attention. If I give them proper respect, value them, take their problems seriously, I find that they respect me back – and interruption is rare unless it really is necessary.

So if you really can't deal with the interruption fully there and then, at least find some compromise. It will pay you back in the long run.