I once worked for a young organisation with big ambitions. The managers were all highly experienced, but had only recently come together as a team. They decided to contract with a long-established and very stable international firm to help with operations.

I don’t think anybody was expecting what happened next. The partner firm arrived, and immediately started to call the shots. Needless to say, hackles rose amongst my colleagues – we were the customer, after all: isn’t the customer always right? It took some considerable (and uncomfortable) time to make the relationships work.

What happened? This was all about organisational maturity. The partner organisation had well-established ways of doing things and strong internal relationships. Everyone knew what they were there to do, and how it related to everyone else. They knew that their colleagues could be trusted to do what they expected, and to back them up when necessary. That organisational maturity gave them a high degree of confidence.

My organisation, on the other hand, had none of that. Although individuals (as individuals) were highly competent and confident, there had not been time for strong relationships to develop between us. Although there would be an expectation of support from others, without having been there before certainty about its strength, timeliness and content was lacking. In those circumstances, collective confidence cannot be high. Eventually our differences were sorted out, but it might have been quicker and easier if the relative lack of organisational maturity and its consequences had been recognised at the start.

Confidence comes not just from the confidence of individuals. It is also about the strength of teamwork, and a team has to work together for some time to develop that trust and mutual confidence. When two organisations interact, expect their relative maturities to affect the outcome.

Many years ago I used to make pottery as a hobby. After a few years I got to be good enough that friends sometimes asked me to make pots for them. Of course, that is when things start to get a bit difficult – what to charge them? I could have said “I’m a hobby potter – if I cover my costs, that will be fine.” But then, if a friend asked me to make something (in principle at least) it was instead of buying from someone who was trying (and mostly struggling) to make a living out of potting. For someone like me to undercut them seemed wrong. I always charged about what I thought they would have had to pay a ‘real’ potter for something similar. That way I felt that they were choosing my work just because they liked what I made. When I explained, everyone thought that was fair.

Over the years, I have learnt just how important it is to value yourself appropriately. I once took a job at a rather lower salary than I had been used to, rather than continue the uncertainty of searching until I found a better one. I discovered that because I had accepted that valuation of myself, understandably everyone else did too. The job didn’t challenge me, so I got bored, but it seemed to be impossible to persuade anyone within the organisation that I could be adding more value if only they would ask me to work on some more difficult problems – of which there were plenty. The job I was doing needed to be done. Before long, I left to go to a job at a more appropriate level.

This can be a difficult balance for an interim manager. Price is only an imperfect proxy for the value of the job, but what a customer expects to pay is usually a good indication of how they see it. We all need to pay the bills, but accepting a disparity in price perceptions is not usually a good basis for a satisfying relationship in any kind of transaction.

Many years ago I used to make pottery as a hobby. After a few years I got to be good enough that friends sometimes asked me to make pots for them. Of course, that is when things start to get a bit difficult – what to charge them? I could have said “I’m a hobby potter – if I cover my costs, that will be fine.” But then, if a friend asked me to make something (in principle at least) it was instead of buying from someone who was trying (and mostly struggling) to make a living out of potting. For someone like me to undercut them seemed wrong. I always charged about what I thought they would have had to pay a ‘real’ potter for something similar. That way I felt that they were choosing my work just because they liked what I made. When I explained, everyone thought that was fair.

Over the years, I have learnt just how important it is to value yourself appropriately. I once took a job at a rather lower salary than I had been used to, rather than continue the uncertainty of searching until I found a better one. I discovered that because I had accepted that valuation of myself, understandably everyone else did too. The job didn’t challenge me, so I got bored, but it seemed to be impossible to persuade anyone within the organisation that I could be adding more value if only they would ask me to work on some more difficult problems – of which there were plenty. The job I was doing needed to be done. Before long, I left to go to a job at a more appropriate level.

This can be a difficult balance for an interim manager. Price is only an imperfect proxy for the value of the job, but what a customer expects to pay is usually a good indication of how they see it. We all need to pay the bills, but accepting a disparity in price perceptions is not usually a good basis for a satisfying relationship in any kind of transaction.  Have you ever noticed that the fruit and nuts in your breakfast muesli tend to stay at the top of the packet? So that when you are getting toward the end of the packet, you are usually left with mostly the boring bits?

There is a simple explanation. When there are many large lumps (the fruit and nuts) together, they have large holes in between them, and smaller lumps (the oats) can fall through the holes. When many small lumps are together, they have small holes in between them, so large lumps can’t fall through. Consequently, with gentle shaking there is a tendency for the large and small lumps to separate, with the large lumps at the top.

Interesting, but so what? Well, perhaps the same sort of thing happens with the order of work activities. The interesting, strategic lumps stay at the top and get done first. The boring – or difficult – bits may fall through the cracks, or at least get left to others or to later. The trouble is that to have a nutritionally balanced diet, we need the whole mixture, not just the exciting bits. Good delivery requires us to stick to doing things in the best order, even when that means tackling early some activities we would rather leave till later.

Have you ever noticed that the fruit and nuts in your breakfast muesli tend to stay at the top of the packet? So that when you are getting toward the end of the packet, you are usually left with mostly the boring bits?

There is a simple explanation. When there are many large lumps (the fruit and nuts) together, they have large holes in between them, and smaller lumps (the oats) can fall through the holes. When many small lumps are together, they have small holes in between them, so large lumps can’t fall through. Consequently, with gentle shaking there is a tendency for the large and small lumps to separate, with the large lumps at the top.

Interesting, but so what? Well, perhaps the same sort of thing happens with the order of work activities. The interesting, strategic lumps stay at the top and get done first. The boring – or difficult – bits may fall through the cracks, or at least get left to others or to later. The trouble is that to have a nutritionally balanced diet, we need the whole mixture, not just the exciting bits. Good delivery requires us to stick to doing things in the best order, even when that means tackling early some activities we would rather leave till later.

Planet K2 shared this great TED talk about how limitations can help creativity. But how is that relevant to management?

As managers, we always have to work within many limitations: it is the nature of the world we work in. Contracts of all kinds; laws and regulations; stakeholder wishes; all constrain the freedom we have to act. If we see our job as managers being to make sure that we comply with all these requirements – some of which may well be conflicting, making that task ultimately impossible – there is a good chance we will start a downwards spiral of attempting ever-tighter control while only making things worse, as artist Phil Hansen found. We become more and more stressed, and less and less able to meet all those requirements.

How much better to recognise that while the limitations rule out some options, those very limitations can help us to focus our imaginations on the many other options which we may not have considered, but which remain available (and which, as Hansen found, can still present an overwhelming range of possibilities). When you squeeze the balloon, it pops out somewhere else. That requires us to have the courage to be creative, to try new approaches which have some risk of failure – but that makes success all the more satisfying and rewarding, as well as helping to free us to continue down the route of creativity.

Hansen found that what seemed to be the end of his dream of a creative life was in fact the door to whole new worlds of creativity. Rather than try too hard to work within our constraints, let’s use them to help us find the ways to better solutions, as he did.

Planet K2 shared this great TED talk about how limitations can help creativity. But how is that relevant to management?

As managers, we always have to work within many limitations: it is the nature of the world we work in. Contracts of all kinds; laws and regulations; stakeholder wishes; all constrain the freedom we have to act. If we see our job as managers being to make sure that we comply with all these requirements – some of which may well be conflicting, making that task ultimately impossible – there is a good chance we will start a downwards spiral of attempting ever-tighter control while only making things worse, as artist Phil Hansen found. We become more and more stressed, and less and less able to meet all those requirements.

How much better to recognise that while the limitations rule out some options, those very limitations can help us to focus our imaginations on the many other options which we may not have considered, but which remain available (and which, as Hansen found, can still present an overwhelming range of possibilities). When you squeeze the balloon, it pops out somewhere else. That requires us to have the courage to be creative, to try new approaches which have some risk of failure – but that makes success all the more satisfying and rewarding, as well as helping to free us to continue down the route of creativity.

Hansen found that what seemed to be the end of his dream of a creative life was in fact the door to whole new worlds of creativity. Rather than try too hard to work within our constraints, let’s use them to help us find the ways to better solutions, as he did.  I went to a fascinating talk by Adam Hoyle, Managing Director, Tradax Group Ltd, on Corporate Best Practice in Public Sector Bidding. I thought there were a number of lessons that apply more generally to running all kinds of projects that would be worth sharing.

I went to a fascinating talk by Adam Hoyle, Managing Director, Tradax Group Ltd, on Corporate Best Practice in Public Sector Bidding. I thought there were a number of lessons that apply more generally to running all kinds of projects that would be worth sharing.

Seven best practice tips

- Don’t start projects unless they align with your overall strategy

- Make sure you have thought through exactly what decision-making authority each person involved should have, and that this has been clearly communicated and understood

- Give everyone involved a clear written briefing pack at the start, providing them with all the basic information about the project that they will require

- Standardise what you can – but everything that is standardised needs an owner who takes their ownership seriously

- Think hard about what information would really make a difference to your performance if you had it, and work creatively (legally of course) to get it – for example using FoI requests

- Use the information you have intelligently – there is probably much more that you can learn than is immediately obvious, if you put it all together

- Transitions between teams – for example on winning a bid, or starting to operate an asset – are high-risk boundaries, which need careful planning to make sure they go smoothly

This is article 7 in my series on designing internal governance.

As we discussed at the start of these articles, the need for governance arises because we want to be able to exercise the degree of control we need over our organisation. In the previous six articles, the structures we may establish to provide this have been discussed at some length. However, we might as well not bother unless we communicate clearly and effectively what we have set up, why, and how it helps everyone! This article considers what documentation is required in order to support good internal governance.

Talking people through the way the governance is intended to work is always a good idea. People listen when you tell them stories – and I know I often stop listening when there isn’t some kind of story – because story is how we make sense of things. Talking about how it should work allows you to weave in stories about why it is the way it is, as I have tried to do in these articles, which may maintain interest and help people to see the benefits as well as the irritations.

Documentation for governance

However, talking alone is not enough. The story people hear is not always exactly the one you told. If it was not written down, who is to say whose memory is right? Documentation is there to make sure that there is a definitive reference point to go back to when disagreements arise. There is a good reason why, although verbal contracts are legally binding, people generally prefer the written sort!Governance as a contract

Think of governance as a form of contract: we specify what authority we are giving, to whom and under what circumstances, and what accountability we are getting in return. The documentation records the terms of the contract, shows that it was agreed, and provides evidence that it was complied with. The documentation required for governance should balance the need to avoid unnecessary bureaucracy with the need for documents which can resolve later differences of opinion, provide traceability and auditability, and also (depending on circumstances) meet the need for transparency. Authorities delegated should be clearly set out in Letters of Appointment (Individual) or in Terms of Reference (Collective), signed as issued by an authorised person, and signed as accepted by the person being authorised. You don’t want to hear "I never received that", or "that's not what I understood". Where Collective authority is granted, as a minimum there must be a written record of all decisions made, and of those present at the time (to demonstrate that the quorum was present, so that the terms of the delegation were satisfied).Words matter!

Documentation is about communication, not just about record keeping. The language used matters. This is difficult: clearly where important decisions are made, accuracy is essential, but it must not be at the expense of intelligibility by all. Old-fashioned legalese may have been very precise in its meaning, provided you understood the code, but was almost as unintelligible as a foreign language to most people. If you want people to stick to what you meant to authorise them to do, and to accept accountability for what you expect, there is no room for ambiguity. Woolly or opaque language makes it easy for people to say “Oh, that’s not what I thought you meant”. Use plain English, short sentences, simple constructions, and not convoluted prose, as far as you can. Don’t use several words when one will do! Even better, use diagrams where appropriate. But however hard that is, write it down somehow: however it is written, it is always better than nothing!Principles to be established:

- What formal documentation (e.g. Terms of Reference, Letters of Appointment) is appropriate

- The circumstances where formal authorisation and/or acceptance of documentation will be required

- How widely the arrangements will be communicated

This is article 6 in my series on designing internal governance.

You have decided on your meeting structure, what each meeting is for and how much authority it has. This article is about choosing members of internal governance meetings.

Cabinet Responsibility

A good place to start this discussion is with Government, and the concept of Cabinet Responsibility. On most matters, however hard the arguments behind closed doors, and whatever their personal views, Cabinet members are expected to support the decisions made – or to resign if they cannot. They are party to making those decisions, and they must own the outcome. Collective Accountability in governance is a similar concept. But in choosing members of internal governance meetings, we have to remember what we are trying to achieve. What happens when you fail to involve people in making decisions that will affect them? I’ve seen a variety of reactions, but what you can’t expect is that it will make no difference. Put yourself in that situation: how do you react? Initially the person will probably be angry, although not necessarily openly so. If nothing is done to put things right, at the very least they will give you less commitment; it is quite possible that they will feel an impulse to allow (or even encourage) things to go wrong, to prove their point, and not all of them will successfully resist it. At the other extreme, I was recently at a meeting attended by 35 people, of whom I think 8 spoke. Was there really 27 hours-worth of value from the rest attending? I doubt that that sort of attendance does anything for ownership, anyway. Large meetings not only waste time, they tend to encourage grandstanding, and inhibit the full and frank discussions which may be necessary, but which are better not held in front of a large audience. Being a member of the meeting can be seen as a matter of status, so there is also a need to separate genuine needs for inclusion from status-based ones.Choosing members of internal governance meetings: inclusivity versus efficiency

Deciding membership of Collective Authority bodies requires balancing the desire for inclusivity (more people) with the need for the body to be efficient (fewer people). Remember why we use collective authority: to ensure that decisions are owned by all those who need to own them. Identify who that will be, given the Terms of Reference expected, and choose members accordingly, remembering to check that the resulting membership is also appropriate for the level of delegated authority to be granted. It is likely that this will mean that most members are of a similar level in the organisation; this is in any case usually required for effective debates. Where necessary, specialists or team members may attend meetings to provide knowledge of detail. However, this does not mean that they need be members, nor that they count towards the quorum – nor that they can come next time! They should generally only attend for the item that they are supporting. Create the right expectation at the start: it is hard to send people out if a pattern of not doing so has developed. Normally the Chair of a “parent” meeting will not be a member of subsidiary meetings (remember that in a hierarchy, every meeting has one and only one parent meeting from which they receive their authority!), but if, exceptionally, they are, there may be an expectation that as (probably) the most senior person present, they should chair that meeting also. This is not helpful for clarity, as it results in the difference in authority levels between the meetings being less clear. If they are there, it should be because they have expertise which is required, not because of their seniority. If a subsidiary meeting’s membership looks almost the same as the membership of its parent meeting, it is worth considering whether they are really different meetings, or whether the matters to be considered should simply be reserved at the higher level. If not, then the membership should be slimmed down.Principles to establish:

- That the list of staff (or roles) to be included as members in the Collective Authority arrangements will balance the need for ownership of decisions with minimum meeting membership

- That clear rules for meeting attendance will be agreed and maintained

This is article 5 in a series about designing internal governance.

I once worked in an organisation which needed to procure many large construction projects. Nearly all of these were subject to European Union procurement rules, which make specific steps in the procurement processes mandatory, and which create some short deadlines despite lasting months overall. It’s a bit like a game of Snakes and Ladders (but without the ladders): if things go wrong you may have to start all over again. Consequently, inability to control the processes well is a serious risk. This article is about how to get delegation and escalation right.

Unfortunately, the general level of authority delegated to the local Board was a fraction of the contract value for most of the procurements, meaning that awarding these contracts needed the approval of the main Board. They normally met only about every 2 months, and had little knowledge of the issues. Control of that process was out of our hands. Very careful planning (and significant extra work) was required to minimise the risk of failing to get properly-authorised approvals at the necessary times, and so avoid the ‘snakes’.

Fortunately, once we were able to demonstrate that we had well-managed internal governance, more appropriate delegations were granted. Nevertheless, the example illustrates the problems that can arise when the level of delegations is not appropriate to the required decisions.

Note that it is normal for Boards to have ‘Reserved Matters’ which are not delegated at all; the same principle will apply at lower levels as well. Just because there is a box on the authority grid does not mean it has to be filled!

Principles to establish:

Delegation and escalation levels: getting the balance right

Deciding what authority to delegate requires balancing the need for control with the need for practical delivery, which includes the need for timely decisions. The place to start is the levels of authority to be delegated. What will meet the business need, taking account of the volume of decisions are required, and which it is practical to make in the time available at different levels? The membership of the bodies to which delegation is made then follows: it should be chosen to ensure that the members have the competence they will need. If you start with the membership, and then decide what decisions they can be trusted with, the result may not deliver what the business needs. A delegated authority generally consist of two parts: a subject and a value or scale limit. The subjects will probably be the same at different levels in the hierarchy, but the scale limits will vary. A decision which exceeds the limit at one level must be escalated up the structure, perhaps with a transition from Individual to Collective Authority part way up. It is convenient to articulate both the subjects and the authority limits in an authority grid or scheme of delegations. Obviously there will normally be one or more columns for financial and budget matters. A programme organisation might also require columns such as changes to delivery time, changes to scope and requirements, and quality assurance (see example grid below). Obviously, other kinds of organisations will have other requirements. How will you decide what the authority levels should be? This is another question of balance, this time between the desire to encourage ownership and accountability at lower levels, and the need to retain senior accountability for the bigger decisions. While this can never be a precise science, limits should generally be set so that the proportion of all the decisions which come to a body (or indeed an individual) and which must be escalated to a higher level is expected to be fairly small – perhaps 10-20%. This pattern, repeated at each level and interpreted intelligently, ensures that the Board (and each level below it) sees what it needs to see, without being overwhelmed by volume or delaying decisions unnecessarily. Equally importantly, each lower level feels it has the trust of its superiors and is empowered to do its job.Authority grid

While setting such limits for financial decisions is straightforward because the escalation levels are easily quantified, it is not quite so simple (although just as important) in other areas. However, in these cases practical qualitative tests can work perfectly well. The illustrative authority grid shown includes examples of tests which are still sufficiently objective to be useful.| Category | Requirements | Financial/Budget | Time | Quality | Control |

| Level A | Set overall strategic direction | Budget including contingency Larger budget changes | Approve third line assurance | Appoint Level B Cancel a programme | |

| Level B | Approve programme scope & requirements Approve changes to scope & requirements | Change allocations within portfolio contingency | Changes which delay benefits delivery | Approve second line assurance, commission third line assurance | Appoint Level C Initiate programme and approve business case Close programme on completion |

| Level C | Approve design and outputs as meeting requirements Approve design or output changes which meet requirements | Change allocations within programme contingency | Changes with no impact on benefit delivery | Approve first line assurance, provide/ commission second line assurance | Appoint Level D Options selection Approve stage gates, output acceptance & readiness to proceed Accept key milestone completion |

| Level D | Change allocations within project contingency | Changes with no impact on key milestones | Commission first line assurance | Accept project milestone completion |

- That the authority grid should include qualitative as well as quantitative delegation limits, and should not be restricted to areas where a financial limit can be set

- That escalation levels will be set to provide an appropriate level of filtering, decided on the basis of business need and practical delivery

- That decisions about committee membership should be made in the light of the delegation levels set

This is article 4 in my series on designing internal governance.

Some while ago, I was asked to map part of the internal decision-making structure (below Board level) in an organisation I was working in. I talked to the people involved, asking where decisions came to them from, and where they were passed on to, and followed the chain. That exercise taught me a lot about hierarchy in internal governance!

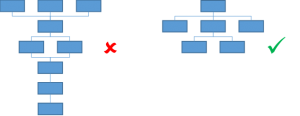

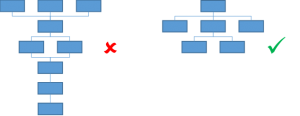

The overall picture that emerged was not very clear, which was not a good start (no surprise that everyone else was confused!). However, there were some things that I could say for certain. There were at least six layers: that sounds like a lot of people, a lot of time, and almost certainly a lot of delay, in making decisions. In the middle of the escalation route, there appeared to be a loop: at that level, there were two possible places for the next decision to get made. I still don’t know why, or how you would decide which side of the loop to go round, or what the body not consulted would have thought. And finally – worst of all – if you had to go all the way up the chain, there were three separate bodies at the top! I have no idea how any conflict would have been resolved. I don’t believe that the structure had been deliberately set up like that – it had just evolved. Needless to say, the organisation no longer exists.

Hierarchy in internal governance: What does good look like?

What would a good structure look like? Good governance requires a simple (upside-down) tree structure. As you go up, several branches may join together, but no branch ever divides. Everything comes together at one body (the Board, reporting to shareholders) at the top. A fundamental point that is sometimes forgotten is that no governance body can be free-standing: if it is not part of the hierarchy it is not part of governance! In deciding what governance bodies we need and how they should relate to each other, we need to find the right balance between, on the one hand, simplicity and clarity of the structure, and, on the other, efficiency and effectiveness in decision-making. Governance only works well if everyone understands it. A simple structure with very few ‘branches’ is simple and easy to understand, but can overload the small number of decisions makers, and may not be very inclusive. On the other hand, a greater number of more specialised meetings, while more ‘expert’ and perhaps more efficient for decision making, will add complexity, reduce clarity, be less joined-up, and be harder to service. So where do we start? All authority within an organisation initially rests with its Board. It then makes specific delegations of that authority. The authority it delegates in turn rests where it is delegated, unless it is specifically sub-delegated by that body. The authority to sub-delegate should be specifically stated (or withheld) in the Terms of Reference; by definition, the lowest tier of Collective Authority bodies cannot have this authority. A body may only delegate authority which it holds itself, and then only if it also has been given the specific authority to do so. These rules naturally create a simple tree structure as described above. The decisions to be made in setting up the structure are- How many levels does it need?

- What is the best way to group the delegated decisions within a level?

Principles to establish:

- That the governance structure will be strictly hierarchical, and that all bodies which have Collective Authority will have a place within that hierarchy;

- That the design will proceed by establishing those areas where the Board should make delegations (starting by noting the matters already reserved to the Board), and how they should be grouped

- What (if any) dual-key arrangements are desirable?

I have been reading

I have been reading