[caption id="" align="alignright" width="300"] Queueing for the Proms 2008 on the south steps of the Royal Albert Hall (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

I’m sitting on the steps outside the Royal Albert Hall in London. Fortunately today it isn’t raining, but even if it was, I needn’t worry. These days the Proms have an excellent system for managing the queue – rather like the ones on the deli counters in supermarkets. When you arrive, you are given a numbered ticket, which guarantees your place in the queue. Once you have your ticket, you can wander off for a coffee or a snack, or take shelter if it rains, knowing that everyone will be admitted in the order they joined the queue regardless. It is not particularly sophisticated – but it is a simple system, and it works.

Simplicity is hard-fought-for: it does not happen by accident. Once a complex process or system is in place, changing it to remove unnecessary complexity is hard, just as all change is. Even stopping a simple system getting more complicated needs constant vigilance: otherwise, it is likely to gather exceptions and special cases, as well as extra checks that seem important, but which have a cost which is frequently overlooked. Just as nature dictates that the disorder of the Universe (or a teenager’s bedroom) increases with time, and that this can only be reversed by the input of work, so it is with organisations.

Why does it matter? Because a simple system is inherently more efficient and less error-prone. Have you tried to explain your organisation’s processes to a new joiner? If so, how easy do you find it to explain the judgements required if the process has branches (if this, then that, but if not, then the other), and how quickly do people learn to make them properly? Good governance depends on people following the rules. Complexity makes it more likely that people will make mistakes, and also makes it harder to spot when people deliberately try to get round rules. For an extreme example of what happens with complexity, think about tax codes: with complex rules and many special cases, expert advisers earn a good living, which must be at the expense of either the tax-payer or the tax-collector or both. While that is good for the experts, does that not make its complexity bad for the rest of us?

Queueing for the Proms 2008 on the south steps of the Royal Albert Hall (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

I’m sitting on the steps outside the Royal Albert Hall in London. Fortunately today it isn’t raining, but even if it was, I needn’t worry. These days the Proms have an excellent system for managing the queue – rather like the ones on the deli counters in supermarkets. When you arrive, you are given a numbered ticket, which guarantees your place in the queue. Once you have your ticket, you can wander off for a coffee or a snack, or take shelter if it rains, knowing that everyone will be admitted in the order they joined the queue regardless. It is not particularly sophisticated – but it is a simple system, and it works.

Simplicity is hard-fought-for: it does not happen by accident. Once a complex process or system is in place, changing it to remove unnecessary complexity is hard, just as all change is. Even stopping a simple system getting more complicated needs constant vigilance: otherwise, it is likely to gather exceptions and special cases, as well as extra checks that seem important, but which have a cost which is frequently overlooked. Just as nature dictates that the disorder of the Universe (or a teenager’s bedroom) increases with time, and that this can only be reversed by the input of work, so it is with organisations.

Why does it matter? Because a simple system is inherently more efficient and less error-prone. Have you tried to explain your organisation’s processes to a new joiner? If so, how easy do you find it to explain the judgements required if the process has branches (if this, then that, but if not, then the other), and how quickly do people learn to make them properly? Good governance depends on people following the rules. Complexity makes it more likely that people will make mistakes, and also makes it harder to spot when people deliberately try to get round rules. For an extreme example of what happens with complexity, think about tax codes: with complex rules and many special cases, expert advisers earn a good living, which must be at the expense of either the tax-payer or the tax-collector or both. While that is good for the experts, does that not make its complexity bad for the rest of us?

Queueing for the Proms 2008 on the south steps of the Royal Albert Hall (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

I’m sitting on the steps outside the Royal Albert Hall in London. Fortunately today it isn’t raining, but even if it was, I needn’t worry. These days the Proms have an excellent system for managing the queue – rather like the ones on the deli counters in supermarkets. When you arrive, you are given a numbered ticket, which guarantees your place in the queue. Once you have your ticket, you can wander off for a coffee or a snack, or take shelter if it rains, knowing that everyone will be admitted in the order they joined the queue regardless. It is not particularly sophisticated – but it is a simple system, and it works.

Simplicity is hard-fought-for: it does not happen by accident. Once a complex process or system is in place, changing it to remove unnecessary complexity is hard, just as all change is. Even stopping a simple system getting more complicated needs constant vigilance: otherwise, it is likely to gather exceptions and special cases, as well as extra checks that seem important, but which have a cost which is frequently overlooked. Just as nature dictates that the disorder of the Universe (or a teenager’s bedroom) increases with time, and that this can only be reversed by the input of work, so it is with organisations.

Why does it matter? Because a simple system is inherently more efficient and less error-prone. Have you tried to explain your organisation’s processes to a new joiner? If so, how easy do you find it to explain the judgements required if the process has branches (if this, then that, but if not, then the other), and how quickly do people learn to make them properly? Good governance depends on people following the rules. Complexity makes it more likely that people will make mistakes, and also makes it harder to spot when people deliberately try to get round rules. For an extreme example of what happens with complexity, think about tax codes: with complex rules and many special cases, expert advisers earn a good living, which must be at the expense of either the tax-payer or the tax-collector or both. While that is good for the experts, does that not make its complexity bad for the rest of us?

Queueing for the Proms 2008 on the south steps of the Royal Albert Hall (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

I’m sitting on the steps outside the Royal Albert Hall in London. Fortunately today it isn’t raining, but even if it was, I needn’t worry. These days the Proms have an excellent system for managing the queue – rather like the ones on the deli counters in supermarkets. When you arrive, you are given a numbered ticket, which guarantees your place in the queue. Once you have your ticket, you can wander off for a coffee or a snack, or take shelter if it rains, knowing that everyone will be admitted in the order they joined the queue regardless. It is not particularly sophisticated – but it is a simple system, and it works.

Simplicity is hard-fought-for: it does not happen by accident. Once a complex process or system is in place, changing it to remove unnecessary complexity is hard, just as all change is. Even stopping a simple system getting more complicated needs constant vigilance: otherwise, it is likely to gather exceptions and special cases, as well as extra checks that seem important, but which have a cost which is frequently overlooked. Just as nature dictates that the disorder of the Universe (or a teenager’s bedroom) increases with time, and that this can only be reversed by the input of work, so it is with organisations.

Why does it matter? Because a simple system is inherently more efficient and less error-prone. Have you tried to explain your organisation’s processes to a new joiner? If so, how easy do you find it to explain the judgements required if the process has branches (if this, then that, but if not, then the other), and how quickly do people learn to make them properly? Good governance depends on people following the rules. Complexity makes it more likely that people will make mistakes, and also makes it harder to spot when people deliberately try to get round rules. For an extreme example of what happens with complexity, think about tax codes: with complex rules and many special cases, expert advisers earn a good living, which must be at the expense of either the tax-payer or the tax-collector or both. While that is good for the experts, does that not make its complexity bad for the rest of us?

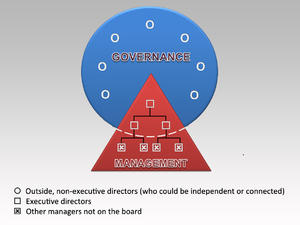

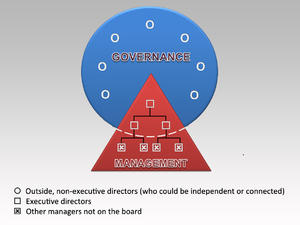

[caption id="" align="alignright" width="300"] English: Corporate Governance (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

All organisations have to find an appropriate balance between central control and local freedom to act. Governance provides the framework and checks and balances within which this is established and managed. It ensures that the process by which decisions are made is appropriately managed. It allows them to be seen to have been taken in the best interests of the shareholders, taking account of all the demands on the organisation, the risks, and the information available at the time.

English: Corporate Governance (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

All organisations have to find an appropriate balance between central control and local freedom to act. Governance provides the framework and checks and balances within which this is established and managed. It ensures that the process by which decisions are made is appropriately managed. It allows them to be seen to have been taken in the best interests of the shareholders, taking account of all the demands on the organisation, the risks, and the information available at the time.

English: Corporate Governance (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

All organisations have to find an appropriate balance between central control and local freedom to act. Governance provides the framework and checks and balances within which this is established and managed. It ensures that the process by which decisions are made is appropriately managed. It allows them to be seen to have been taken in the best interests of the shareholders, taking account of all the demands on the organisation, the risks, and the information available at the time.

English: Corporate Governance (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

All organisations have to find an appropriate balance between central control and local freedom to act. Governance provides the framework and checks and balances within which this is established and managed. It ensures that the process by which decisions are made is appropriately managed. It allows them to be seen to have been taken in the best interests of the shareholders, taking account of all the demands on the organisation, the risks, and the information available at the time.

Review your governance

If several of the following statements are true of your organisation, it may well be a good idea to review your governance arrangements.- The governance structure (meetings and delegations) does not constitute a simple hierarchy underneath the Board, with clear parent-child relationships and information cascaded up and down the hierarchy

- The governance structure is not clearly documented (e.g. including a consistent set of Terms of Reference), communicated and understood

- People do not have clear written instructions as to the limits of the authority that they have been given, or these are ignored

- Committees are allowed to approve their own Terms of Reference and/or memberships

- Governance meetings happen irregularly, or with papers which are poor quality or issued late

- Senior staff are allowed to ignore the rules which apply to others

- Decisions are often taken late because of papers missing submission dates, inadequate information, wrong attendance, submission to the wrong meeting, unexpected need for escalation, etc

- There is a feeling that the governance process is too bureaucratic

The other night I was meeting a friend for dinner in town. You know how sometimes when you get down to the tube platform it feels wrong? It felt wrong. Too many people, milling about with resigned looks, not purposefully waiting. Then the public announcement: “the Victoria line is suspended from Victoria to Walthamstow Central. There is a shuttle service operating between Brixton and Victoria.”

No train. No boards telling you when the next train is coming either. I have a choice: I can take the chance of waiting, hoping that if a train does come soon I might still be on time – but it might be ages; or I can go out and catch a bus – I will definitely be a bit late, but I know it will definitely come?

The other night I was meeting a friend for dinner in town. You know how sometimes when you get down to the tube platform it feels wrong? It felt wrong. Too many people, milling about with resigned looks, not purposefully waiting. Then the public announcement: “the Victoria line is suspended from Victoria to Walthamstow Central. There is a shuttle service operating between Brixton and Victoria.”

No train. No boards telling you when the next train is coming either. I have a choice: I can take the chance of waiting, hoping that if a train does come soon I might still be on time – but it might be ages; or I can go out and catch a bus – I will definitely be a bit late, but I know it will definitely come?

How do we deal with risk?

It’s a nice example of how we human beings deal with risk. I don’t know about you, but my thought process goes something like this. First I will take the higher risk option – perhaps partly because it is where I am. As I wait, and nothing happens, I weigh up how late I am going to be if I catch the bus. At some point (if I am still waiting) I decide to cut my losses – either way I’m going to be late, so I opt for the more certain course and catch the bus. This time, I waited 10 minutes before changing to Plan B, and was 20 minutes late. If I had changed immediately I would only have been 10 minutes late. It’s not very rational – the sensible thing surely is to take the low risk option as early as possible, minimising the lateness, rather than just hoping that Plan A will avoid us being late at all, and then finishing up being later than we needed to be. But it seems to be human nature to take the optimistic view like this. Usually when we have to deal with risk there is some kind of pain threshold we have to exceed before we are willing to consider an alternative course, even though the sensible point to do so may have been much earlier. I don’t know how much unnecessary pain we suffer as a result, but I suspect it is significant! Do you need help identifying the change options you have to deal with risk? Please get in touch. I’m on my way to a Board meeting. My job as a Board member is to turn up about once a month for a meeting lasting normally no more than a couple of hours to take the most important decisions the company needs – decisions which are often about complex areas, fraught with operational, commercial, legal and possibly political implications, and often with ambitious managers or other vested interests arguing strongly (but not necessarily objectively) for their preferred outcome. Few of the decisions are black and white, but most carry significant risk for the organisation. Good outcomes rely on informing Board members effectively.

This is a well-managed organisation, so I have received the papers for the meeting a week in advance, but I have had no chance to seek clarification of anything which is unclear, or to ask for further information. In many organisations, the papers may arrive late, or they may have been poorly written so that the story they tell is incomplete or hard to understand (despite often being very detailed), or both. The Board meeting, with a packed agenda and a timetable to keep to, is my only chance to fill the gaps.

I have years of experience to draw on, but experience can only take me so far. Will I miss an assumption that ought to be challenged, or a risk arising from something I am not familiar with? If that happens, we may make a poor decision, and I will share the responsibility. In some cases – for instance a safety issue - that might have serious consequences for other people. It’s not a happy thought.

I’m on my way to a Board meeting. My job as a Board member is to turn up about once a month for a meeting lasting normally no more than a couple of hours to take the most important decisions the company needs – decisions which are often about complex areas, fraught with operational, commercial, legal and possibly political implications, and often with ambitious managers or other vested interests arguing strongly (but not necessarily objectively) for their preferred outcome. Few of the decisions are black and white, but most carry significant risk for the organisation. Good outcomes rely on informing Board members effectively.

This is a well-managed organisation, so I have received the papers for the meeting a week in advance, but I have had no chance to seek clarification of anything which is unclear, or to ask for further information. In many organisations, the papers may arrive late, or they may have been poorly written so that the story they tell is incomplete or hard to understand (despite often being very detailed), or both. The Board meeting, with a packed agenda and a timetable to keep to, is my only chance to fill the gaps.

I have years of experience to draw on, but experience can only take me so far. Will I miss an assumption that ought to be challenged, or a risk arising from something I am not familiar with? If that happens, we may make a poor decision, and I will share the responsibility. In some cases – for instance a safety issue - that might have serious consequences for other people. It’s not a happy thought.

Informing Board members

In order for a Board (or any other body) to make good decisions, it has to be in possession of appropriate information. These are some of the rules I have followed when I have set up arrangements to promote effective governance.Good papers

Good papers tell the story completely and logically, but concisely. They do not assume that the reader knows the background. They build the picture without jumping around, and make clear and well-argued recommendations. They do not confuse with unnecessary detail, but nor do they overlook important aspects. As Einstein said, “If you can't explain it simply, you don't understand it well enough." Provide rules on length, apply (pragmatic) quality control to the papers received, and refuse to include papers if they do not meet minimum requirements (obviously it helps to be able to give advice on how to make them acceptable). You must of course choose a reviewer whose judgements will be respected. This may well result in some painful discussions, but people only learn the hard way.Timely distribution

If members do not have time to read the papers properly, it does not matter how good they are. If I am a busy Board member, I may need to reserve time in my diary for meeting preparation, and this is a problem if I cannot rely on papers arriving on time. Set submission deadlines which allow for timely and predictable distribution, and enforce them. Again, be prepared for some painful discussions until people learn.Informal channels

Concise papers and busy Board meetings are never going to allow for deep understanding of context. To overcome this, I have organised informal sessions immediately preceding Board meetings, over a sandwich lunch if the timing requires. Allocate a couple of hours for just two or three topics; bring in the subject experts, but spend most of the time on discussion. Not all Board members will be able to attend every session, but in my experience not only have they found them hugely valuable in building their wider knowledge of the business, but the opportunity to meet more junior staff has been appreciated all round. There are many other ways that informal channels could be set up. Different things will work in different organisations. Key to all of them is building trust: informing Board members properly means allowing them to see things “warts and all”, and trusting a wider group of staff to talk to them.Organisation

To do all of these things effectively, you need to have someone (or in larger organisations a small secretariat team) whose primary objective is to deliver them. This is not glamorous stuff, however important, and it easily gets put to the bottom of the pile without clear leadership. Finally, remember that nothing will happen unless the importance of this is understood at the very top. If the CEO does not set an example by sticking to time and quality rules, no one else will. Years ago, I was managing the sale of a business division. The business was based on carrying out a highly-specialised technical test on clients’ products, and each time a test was carried out, it made a loud bang. This would have been of no concern if it had not been that they were carried out in a large workshop also used for other activities. However, checks had been made and the noise levels were within legal safety limits.

Just before signing the deal, we happened to mention to the purchaser that we had some tests scheduled for the next day, and he said he’d like to send someone round to check the sound levels. It was a beautiful summer’s day – until their measurements showed that the bangs were over the limit. What a toe-curling moment! Clearly, we had made the wrong assumptions.

In the end it was not as bad as it seemed: a sound-attenuating box solved the problem without making access too difficult, at quite modest cost and with only a few weeks’ delay. But the proving tests provided another surprise – the noise levels were legal again without the box. The reason – we now realised – was that the humidity of the air could affect its sound-attenuating properties.

Years ago, I was managing the sale of a business division. The business was based on carrying out a highly-specialised technical test on clients’ products, and each time a test was carried out, it made a loud bang. This would have been of no concern if it had not been that they were carried out in a large workshop also used for other activities. However, checks had been made and the noise levels were within legal safety limits.

Just before signing the deal, we happened to mention to the purchaser that we had some tests scheduled for the next day, and he said he’d like to send someone round to check the sound levels. It was a beautiful summer’s day – until their measurements showed that the bangs were over the limit. What a toe-curling moment! Clearly, we had made the wrong assumptions.

In the end it was not as bad as it seemed: a sound-attenuating box solved the problem without making access too difficult, at quite modest cost and with only a few weeks’ delay. But the proving tests provided another surprise – the noise levels were legal again without the box. The reason – we now realised – was that the humidity of the air could affect its sound-attenuating properties.

Avoiding wrong assumptions

Conclusion 1 – Make sure you know what factors can affect your assumptions. Wrong assumptions may lead to disaster. Conclusion 2 – Don’t rely on conclusion 1! If something is critical, don’t rely on a modest safety margin – do what you can to increase it early, in case there is something you have not anticipated. Want to kill a good conversation dead instantly? Tell someone you are a physicist!

The editorial column in a professional magazine I sometimes read asked recently ‘what does “physics” mean to you?’ And it’s a good question – which I don’t propose to answer here! But it did set me thinking about what I mean when I say I am a physicist (yes, you guessed, I am), even though it is many years since I have done anything which would normally be called physics.

Want to kill a good conversation dead instantly? Tell someone you are a physicist!

The editorial column in a professional magazine I sometimes read asked recently ‘what does “physics” mean to you?’ And it’s a good question – which I don’t propose to answer here! But it did set me thinking about what I mean when I say I am a physicist (yes, you guessed, I am), even though it is many years since I have done anything which would normally be called physics.

Physics and physicists

Actually, defining physics turns out to be quite hard, because it is as much about a way of approaching problems as it is about the nature of their subjects. Physicists are trained to have a reductionist view of the world, expecting that they will be able to understand complex events by using a relatively small number of (usually simple) ‘laws’. That way of thinking turns out to be useful in many other situations of complexity, even if they are not so susceptible to precision. What is my approach to creating a system of internal governance? First identify the small number of simple key principles it must follow and the constraints it must obey, and then make a system that fits them all. What about defining business processes? Or a relationship with a partner organisation? First identify the small number of simple key principles… you got it. If you can start with simple rules, you have a good chance of finishing up with something understandable. “But business is about people” I hear you say, “you can’t reduce it to mechanics like that!” Actually, I think that is exactly why you need to. That’s why businesses have processes, organisation charts, ISO 9001, and so on. A large business can be a highly complex system, just as the natural world is. And we human beings are not very good at dealing with raw complexity. We like predictability - we like to be able to work out what is going to happen next, or how to achieve the result we want. When something is described as complex, it often means we don’t know how to use our knowledge to make a prediction. We need simple patterns that allow us at least to make reasonable guesses. The same thing applies to dealing with other people – people are also complex, and our ability to trust people is based on the patterns we learn to see in their behaviour. What is a physicist? Someone who is trained to find (and communicate) simple ways of understanding complex systems. If you have a complex business problem, you might do worse than to ask a physicist. Contact me at david@otteryconsulting.co.uk if you need some help with simplification! What approaches do you use to encourage the behaviour you want from employees? And do they have the effect you intended? Are you sure?

When I was a very new manager, I remember being impressed by a retired site director of a multinational company, who told me how he had had a pad of gold-coloured paper stars printed, and how every time he heard of an employee who had done a particularly good piece of work, he would hand-write a thank you on a star and send it. People were proud to receive stars – some even had several pinned up where others could see them. They obviously valued the recognition. But he didn’t say anything about the people who didn’t receive gold stars.

What approaches do you use to encourage the behaviour you want from employees? And do they have the effect you intended? Are you sure?

When I was a very new manager, I remember being impressed by a retired site director of a multinational company, who told me how he had had a pad of gold-coloured paper stars printed, and how every time he heard of an employee who had done a particularly good piece of work, he would hand-write a thank you on a star and send it. People were proud to receive stars – some even had several pinned up where others could see them. They obviously valued the recognition. But he didn’t say anything about the people who didn’t receive gold stars.

Recognition

Recognition is nice for the people who get recognised by such a scheme, but that is only ever going to be a minority – and they may well have been motivated to perform well regardless of the recognition. What about everyone else? Does it improve their performance, or lead to them feeling it is not worth bothering? Some schemes try to be more inclusive, but a recent study (http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/6946.html) shows that, unless carefully designed, such an award scheme may actually demotivate good performers, while not necessarily having the expected effect on others. Good performers feel annoyed that now others will gain by doing what they had been doing all along without the benefit of the new reward, and those who are only motivated by the benefit act so as to get it with as little effort as possible. A lot of thought is needed to avoid unintended consequences. I have never had any stars printed. Instead, I have always tried to thank anyone who did a good piece of work for me personally, and to explain to them why I was impressed. Like most people, I'm sure I could and should do that more than I do. What happens? They can’t pin my words on the wall, and it may be that no-one else hears, but each time, I think the relationship becomes a little bit less formal, a little bit less boss and employee, a bit more personal and a little bit more trusting. I believe a good relationship is the most powerful reason why people try harder – and that that will never come from something like a company award scheme. But no, I can’t prove it! Such a simple question, but what a profound difference! A recent article in HBR [http://hbr.org/2013/03/do-you-play-to-win-or-to-not-lose/ar/1 ] shows that this aspect of personality can trump others when it comes to determining fit.

Such a simple question, but what a profound difference! A recent article in HBR [http://hbr.org/2013/03/do-you-play-to-win-or-to-not-lose/ar/1 ] shows that this aspect of personality can trump others when it comes to determining fit.