Organisations need two essential frameworks to be able to deliver effectively, both of which must be consistent with the organisation’s vision and mission: strategy and culture. Strategy, describing WHAT they will deliver, and Culture, defining HOW they will deliver it. Usually lots of effort is put into defining the strategy, but culture often just ‘happens’. Nonetheless, success depends on the two working harmoniously together. Take a look at this article for another view of this.

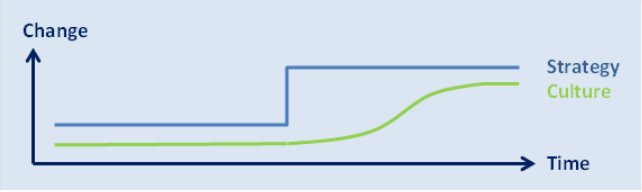

What happens when an organisation faces a disruptive change to its environment? This might be something like an economic or technological change, or, for a major project, might just be moving from promotion to delivery. The first step is usually to update the strategy (and possibly the vision and mission as well) to respond to the change.

So what’s the problem? I think it is that frequently there is no recognition that the change may also require changes to culture to keep it aligned with the strategy. But even if such a change is planned and managed, culture stems from the way people think and behave, and changing it relies on people changing: it cannot be made to change quickly, and certainly not at the same speed as the strategy changes. The disruptive change to strategy then leads to a misalignment between strategy and culture, and this takes time to heal.

Here are two examples where strategy and culture both mattered:

Privatisation

I once worked at a public sector organisation that was privatised. There was a massive (even though long-anticipated) disruptive change in the environment when the transfer happened. Overnight, share price and city reaction to performance became critical, and even though strategy had been becoming more commercial for some while, suddenly it really mattered. Some staff were simply unable to make the cultural shift required for alignment – meaning that until most of those had left or retired, the culture did not become fully commercial. Unfortunately, this process took years – years we did not have.

Major project transition

I also once worked for an organisation set up to plan and build a major infrastructure project. Having for years been focussed on planning and promoting the project, following approval, it suddenly had the challenge of delivering a huge construction project. What had been a fairly small public sector organisation with centralised decision making needed to become an effective delivery organisation in short order. To gain the necessary scale and capability, it let large contracts to firms which were highly experienced in delivering large infrastructure projects. While they brought the energy and focus essential for delivery, it took much longer to bring about an organisational culture that was aligned across staff from all three organisations.

Transition is hard because it requires managing these very different strands in a joined-up way. It needs, on the one hand, the development and implementation of new strategies, requiring vision, analysis, and delivery skills; on the other, bringing about a realignment of culture with minimum delay, requiring people, communication and change skills. And to join them up, it also needs a tolerance for the ambiguity that results while strategy and culture remain out of alignment.

If you are facing a disruptive change, and would like to talk about how to manage the consequences in a joined-up way, contact david@otteryconsulting.co.uk.

Organisations need two essential frameworks to be able to deliver effectively, both of which must be consistent with the organisation’s vision and mission: strategy and culture. Strategy, describing WHAT they will deliver, and Culture, defining HOW they will deliver it. Usually lots of effort is put into defining the strategy, but culture often just ‘happens’. Nonetheless, success depends on the two working harmoniously together. Take a look at this article for another view of this.

What happens when an organisation faces a disruptive change to its environment? This might be something like an economic or technological change, or, for a major project, might just be moving from promotion to delivery. The first step is usually to update the strategy (and possibly the vision and mission as well) to respond to the change.

So what’s the problem? I think it is that frequently there is no recognition that the change may also require changes to culture to keep it aligned with the strategy. But even if such a change is planned and managed, culture stems from the way people think and behave, and changing it relies on people changing: it cannot be made to change quickly, and certainly not at the same speed as the strategy changes. The disruptive change to strategy then leads to a misalignment between strategy and culture, and this takes time to heal.

Here are two examples where strategy and culture both mattered:

Privatisation

I once worked at a public sector organisation that was privatised. There was a massive (even though long-anticipated) disruptive change in the environment when the transfer happened. Overnight, share price and city reaction to performance became critical, and even though strategy had been becoming more commercial for some while, suddenly it really mattered. Some staff were simply unable to make the cultural shift required for alignment – meaning that until most of those had left or retired, the culture did not become fully commercial. Unfortunately, this process took years – years we did not have.

Major project transition

I also once worked for an organisation set up to plan and build a major infrastructure project. Having for years been focussed on planning and promoting the project, following approval, it suddenly had the challenge of delivering a huge construction project. What had been a fairly small public sector organisation with centralised decision making needed to become an effective delivery organisation in short order. To gain the necessary scale and capability, it let large contracts to firms which were highly experienced in delivering large infrastructure projects. While they brought the energy and focus essential for delivery, it took much longer to bring about an organisational culture that was aligned across staff from all three organisations.

Transition is hard because it requires managing these very different strands in a joined-up way. It needs, on the one hand, the development and implementation of new strategies, requiring vision, analysis, and delivery skills; on the other, bringing about a realignment of culture with minimum delay, requiring people, communication and change skills. And to join them up, it also needs a tolerance for the ambiguity that results while strategy and culture remain out of alignment.

If you are facing a disruptive change, and would like to talk about how to manage the consequences in a joined-up way, contact david@otteryconsulting.co.uk.

What happens when an organisation grows up? Many things, but it is not so different from a child growing up: it develops organisation maturity.

As a child grows up, it develops its own habits, values, behaviours. It makes friends. It learns how to do things it could not do before. And it learns how to blend and adapt all of those things to create a consistent whole – its personality. With that comes self-confidence.

So it is with an organisation. In a young organisation – even a large one, perhaps formed from a merger – processes and structures may have been patched together un-adapted from different inheritances. Initially, the mixture of values, relationships, and so on, is unlikely to be self-consistent. Although they may be individually very experienced, managers are not used to working together, and do not know how each other will react in different circumstances. Trust takes time to develop.

Even for an established organisation, a major disruptive change in its environment can cause the same difficulties. The new environment is unfamiliar and the managers of the organisation may have varying responses. Confidence and trust in each other’s judgement in the new situation need to be re-established. Perhaps new people join the team. Processes and systems may need to be changed, because the organisation and its strategy are no longer aligned.

Nobody expects a small, young organisation to behave like a major corporation. However, with scale comes expectation. If you look like a grown-up, people expect you to behave like a grown-up and to have grown-up relationships. Just as with a child who looks much older than it is, the incongruity can cause difficulty for everyone.

Organisational self-confidence – maturity if you will – matters. When an organisation knows at all levels that ‘this is the way we do things round here’, everyone in it can stand their ground with confidence if they need to, in the knowledge that all their colleagues would back them up. Where there is underlying inconsistency, people do not have that confidence. Then it can feel as if you are standing on your own, rather than backed by a team - the whole is not greater than the sum of the parts. So an organisation in this situation needs to grow up fast.

What does it take to do something about this?

First, recognise the nature of the problem. Fundamentally the challenge is about joining things up. That makes it multi-dimensional, multi-functional, crossing all the silos. That in itself means the response has to be driven or at least supported from the top. It also means that it is best done by someone with no vested interest in the outcome. And while it will require detailed analytical work to understand and correct specific problems, it will also need influencing and people skills to ensure that the solutions are accepted and embraced.

I have worked in a number of organisations which have faced challenges of this sort, and helped them to find their way through them. If you are facing similar challenges which you would like to discuss, please contact me at david@otteryconsulting.co.uk.

Have you ever been in a situation where it is obvious from the way management is behaving that something is going on, but where no-one will explain? If so, how did you react?

Suppose you were selling a division of a business, what would you tell the division staff about what is happening, and when?

Management’s instinct always seems to be to say nothing until staff can be told everything – which might not be until the deal has already been signed. It is hard to argue against the objection that the deal is market-sensitive information, and that telling them anything would risk breaking Stock Exchange rules. But does that argument really hold water?

In asset sale projects I have run, it has always been essential to include in the project team – and therefore to inform - some people from the division concerned:

• They have to supply much of the due diligence information;

• The bidders want to meet the managers;

• And they want to walk round the assets they are buying.

Of course many people not directly involved notice the unusual visitors, the unusual questions, the unusual gathering of documents. They probably hear of a ‘Project X’. They are not stupid. They realise that something is going on.

Have you ever been in a situation where it is obvious from the way management is behaving that something is going on, but where no-one will explain? If so, how did you react?

Suppose you were selling a division of a business, what would you tell the division staff about what is happening, and when?

Management’s instinct always seems to be to say nothing until staff can be told everything – which might not be until the deal has already been signed. It is hard to argue against the objection that the deal is market-sensitive information, and that telling them anything would risk breaking Stock Exchange rules. But does that argument really hold water?

In asset sale projects I have run, it has always been essential to include in the project team – and therefore to inform - some people from the division concerned:

• They have to supply much of the due diligence information;

• The bidders want to meet the managers;

• And they want to walk round the assets they are buying.

Of course many people not directly involved notice the unusual visitors, the unusual questions, the unusual gathering of documents. They probably hear of a ‘Project X’. They are not stupid. They realise that something is going on.

What will you tell them?

So what happens? The rumour mill goes into overdrive. Speculation in the corridors mounts (and is usually much more threatening than the true story would be). Productivity probably falls – the last thing the company wants just now. The potential for (accidentally) unhelpful comments being made to bidders or to media fishing calls grows – and of course you can’t control what you have not told people. Isn’t it better to treat staff as grownups? What will you tell them? Tell them honestly what you can tell them, and they will understand that there are things you can’t. Tell them the confidentiality rules you need them to follow, and why. Listen to their concerns, and tell them more as and when you can. It may seem like the riskier route, but when I have been open, I have always found that people respect the confidence and cooperate willingly. Not only that, but as a result of feeling better about the relationship with you, they often volunteer useful comments or help. Treating people as grownups means trusting them. If you don’t treat them as grownups, why would you be surprised if they don’t behave that way? Your transition is most likely to be smooth if you keep everyone on board during the process. If you would like to talk about how to do that, contact david@otteryconsulting.co.uk. Want to kill a good conversation dead instantly? Tell someone you are a physicist!

The editorial column in a professional magazine I sometimes read asked recently ‘what does “physics” mean to you?’ And it’s a good question – which I don’t propose to answer here! But it did set me thinking about what I mean when I say I am a physicist (yes, you guessed, I am), even though it is many years since I have done anything which would normally be called physics.

Want to kill a good conversation dead instantly? Tell someone you are a physicist!

The editorial column in a professional magazine I sometimes read asked recently ‘what does “physics” mean to you?’ And it’s a good question – which I don’t propose to answer here! But it did set me thinking about what I mean when I say I am a physicist (yes, you guessed, I am), even though it is many years since I have done anything which would normally be called physics.

Physics and physicists

Actually, defining physics turns out to be quite hard, because it is as much about a way of approaching problems as it is about the nature of their subjects. Physicists are trained to have a reductionist view of the world, expecting that they will be able to understand complex events by using a relatively small number of (usually simple) ‘laws’. That way of thinking turns out to be useful in many other situations of complexity, even if they are not so susceptible to precision. What is my approach to creating a system of internal governance? First identify the small number of simple key principles it must follow and the constraints it must obey, and then make a system that fits them all. What about defining business processes? Or a relationship with a partner organisation? First identify the small number of simple key principles… you got it. If you can start with simple rules, you have a good chance of finishing up with something understandable. “But business is about people” I hear you say, “you can’t reduce it to mechanics like that!” Actually, I think that is exactly why you need to. That’s why businesses have processes, organisation charts, ISO 9001, and so on. A large business can be a highly complex system, just as the natural world is. And we human beings are not very good at dealing with raw complexity. We like predictability - we like to be able to work out what is going to happen next, or how to achieve the result we want. When something is described as complex, it often means we don’t know how to use our knowledge to make a prediction. We need simple patterns that allow us at least to make reasonable guesses. The same thing applies to dealing with other people – people are also complex, and our ability to trust people is based on the patterns we learn to see in their behaviour. What is a physicist? Someone who is trained to find (and communicate) simple ways of understanding complex systems. If you have a complex business problem, you might do worse than to ask a physicist. Contact me at david@otteryconsulting.co.uk if you need some help with simplification! What approaches do you use to encourage the behaviour you want from employees? And do they have the effect you intended? Are you sure?

When I was a very new manager, I remember being impressed by a retired site director of a multinational company, who told me how he had had a pad of gold-coloured paper stars printed, and how every time he heard of an employee who had done a particularly good piece of work, he would hand-write a thank you on a star and send it. People were proud to receive stars – some even had several pinned up where others could see them. They obviously valued the recognition. But he didn’t say anything about the people who didn’t receive gold stars.

What approaches do you use to encourage the behaviour you want from employees? And do they have the effect you intended? Are you sure?

When I was a very new manager, I remember being impressed by a retired site director of a multinational company, who told me how he had had a pad of gold-coloured paper stars printed, and how every time he heard of an employee who had done a particularly good piece of work, he would hand-write a thank you on a star and send it. People were proud to receive stars – some even had several pinned up where others could see them. They obviously valued the recognition. But he didn’t say anything about the people who didn’t receive gold stars.

Recognition

Recognition is nice for the people who get recognised by such a scheme, but that is only ever going to be a minority – and they may well have been motivated to perform well regardless of the recognition. What about everyone else? Does it improve their performance, or lead to them feeling it is not worth bothering? Some schemes try to be more inclusive, but a recent study (http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/6946.html) shows that, unless carefully designed, such an award scheme may actually demotivate good performers, while not necessarily having the expected effect on others. Good performers feel annoyed that now others will gain by doing what they had been doing all along without the benefit of the new reward, and those who are only motivated by the benefit act so as to get it with as little effort as possible. A lot of thought is needed to avoid unintended consequences. I have never had any stars printed. Instead, I have always tried to thank anyone who did a good piece of work for me personally, and to explain to them why I was impressed. Like most people, I'm sure I could and should do that more than I do. What happens? They can’t pin my words on the wall, and it may be that no-one else hears, but each time, I think the relationship becomes a little bit less formal, a little bit less boss and employee, a bit more personal and a little bit more trusting. I believe a good relationship is the most powerful reason why people try harder – and that that will never come from something like a company award scheme. But no, I can’t prove it! Such a simple question, but what a profound difference! A recent article in HBR [http://hbr.org/2013/03/do-you-play-to-win-or-to-not-lose/ar/1 ] shows that this aspect of personality can trump others when it comes to determining fit.

Such a simple question, but what a profound difference! A recent article in HBR [http://hbr.org/2013/03/do-you-play-to-win-or-to-not-lose/ar/1 ] shows that this aspect of personality can trump others when it comes to determining fit.

Play to win

‘Promotion-focussed’ people are comfortable with risk, dream big, and think creatively. They play to win – but in their haste and optimism they sometimes come unstuck because they fail to plan for the unexpected. On the other hand, those who are ‘Prevention-focussed’, and who plan carefully and pay attention to detail to make sure that nothing goes wrong, may be better at telling the good ideas from the bad, but are often uncomfortable if they cannot take the time to follow due process. Both types are needed, of course. Most people show some characteristics of both at different times, but most have a dominant focus. People will often find the preferences of someone with the opposite focus hard to understand. Where the relationship is important, this matters. When I shared this idea with a consultant friend, it gave her a new insight into what had happened in her relationship with a recent client. Although her experience had been an excellent fit with the client’s requirements, and she had therefore expected everything to go very smoothly, the engagement was terminated early with recriminations on both sides. Seen through the lens of this idea, my friend’s promotion-focussed style was always going to seem threatening to the prevention-focussed CEO, leading to attempts to constrain her activities – or, as she saw it, to stop her doing the job she had been engaged to do. So when you think about taking – or recruiting to – a new job, make sure you know which focus you have, and think how this fits with the person on the other side of the table. It’s about 5°C outside, and I’ve just heard the chimes of the ice-cream van. Yes, I know its nearly April, and the daffodils are trying to come out, but who would want to put a coat on and go and shiver in the road for five minutes, just to eat something … very cold?

It’s about 5°C outside, and I’ve just heard the chimes of the ice-cream van. Yes, I know its nearly April, and the daffodils are trying to come out, but who would want to put a coat on and go and shiver in the road for five minutes, just to eat something … very cold?