What is leadership about? The very word implies movement. Leadership involves helping other people to find the way from A to B, so all leadership is change leadership of some kind. If we are sticking to A, the people may need managing, but there is not much leading involved. You don’t need a leader if you are not going anywhere.

How many times have you heard people say “if its not broken, why fix it?” Probably you have said it yourself at times. Or “I don’t want to upset the apple cart”? No-one likes change – everyone is more comfortable with the status quo. The trouble is, stability is an illusion, at least in the longer term. Everything grows - or it declines. The organisation that does not change positively is doomed eventually to change negatively.

Change is the whole point of leadership. The joke says “How many psychologists does it take to change a light bulb? One, but it has to want to change!” The job of the leader is to have the vision of where to go to, and then to get people to the point where they want to, or at least accept the need for, change.

What is leadership about? The very word implies movement. Leadership involves helping other people to find the way from A to B, so all leadership is change leadership of some kind. If we are sticking to A, the people may need managing, but there is not much leading involved. You don’t need a leader if you are not going anywhere.

How many times have you heard people say “if its not broken, why fix it?” Probably you have said it yourself at times. Or “I don’t want to upset the apple cart”? No-one likes change – everyone is more comfortable with the status quo. The trouble is, stability is an illusion, at least in the longer term. Everything grows - or it declines. The organisation that does not change positively is doomed eventually to change negatively.

Change is the whole point of leadership. The joke says “How many psychologists does it take to change a light bulb? One, but it has to want to change!” The job of the leader is to have the vision of where to go to, and then to get people to the point where they want to, or at least accept the need for, change.

[caption id="" align="alignright" width="300"] Tyrannosaurus rex, Palais de la Découverte, Paris (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

Evolution is the natural process by which all forms of life adapt to changes in their environment. It is a very slow process, in which many small changes gradually accumulate. It is unplanned and undirected: who knows how the environment may change in the future, and so what adaptations would put us ahead of the game? Successful changes are not necessarily the best possible choices, merely the best of those that were tested. Different individuals start from different places, and so the adaptations which seem to work will vary. Consequently, over time, divergence will occur until different species result, even though each species can be traced back to a common ancestor. But evolution is brutal too: not all species will make it. Some find they have gone down an evolutionary dead end, and some that change is simply too fast for them to adapt to.

Sometimes organisational change can be like this. I once worked for a public-sector organisation which was privatised, so that it had to change from being ‘mission-led’ to being profit-led. Management set out a vision for what it wanted the organisation to become – essentially a similar, unitary, organisation but in the private sector – but was unable to make the radical changes necessary to deliver it fast enough. Evolution carried on regardless as the primary need to survive forced short-term decisions which deviated from the vision. Without a unifying mission as a common guide, different parts of the organisation evolved in different ways to adapt to their own local environments. Fragmentation followed, with a variety of different destinies for the parts, and a few divisions falling by the wayside. Despite starting down their preferred route of unitary privatisation, the eventual destination was exactly what the original managers had been determined to avoid.

What is the lesson? Ideally of course it should be possible to set out a strategic objective, and then to deliver the changes needed to get there. But if the change required is too great, or the barriers mean change is brought about too slowly, the short-term decisions of evolution may shape the future without regard to management intentions. That does not necessarily make the outcome worse in the greater scheme of things: after all, evolution is about survival of the fittest. But natural selection is an overwhelming force, and if short-term decisions are threatening to de-rail management’s strategic plan, it may be wise to take another look at the plan, and to try to work with evolution rather than against it.

Tyrannosaurus rex, Palais de la Découverte, Paris (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

Evolution is the natural process by which all forms of life adapt to changes in their environment. It is a very slow process, in which many small changes gradually accumulate. It is unplanned and undirected: who knows how the environment may change in the future, and so what adaptations would put us ahead of the game? Successful changes are not necessarily the best possible choices, merely the best of those that were tested. Different individuals start from different places, and so the adaptations which seem to work will vary. Consequently, over time, divergence will occur until different species result, even though each species can be traced back to a common ancestor. But evolution is brutal too: not all species will make it. Some find they have gone down an evolutionary dead end, and some that change is simply too fast for them to adapt to.

Sometimes organisational change can be like this. I once worked for a public-sector organisation which was privatised, so that it had to change from being ‘mission-led’ to being profit-led. Management set out a vision for what it wanted the organisation to become – essentially a similar, unitary, organisation but in the private sector – but was unable to make the radical changes necessary to deliver it fast enough. Evolution carried on regardless as the primary need to survive forced short-term decisions which deviated from the vision. Without a unifying mission as a common guide, different parts of the organisation evolved in different ways to adapt to their own local environments. Fragmentation followed, with a variety of different destinies for the parts, and a few divisions falling by the wayside. Despite starting down their preferred route of unitary privatisation, the eventual destination was exactly what the original managers had been determined to avoid.

What is the lesson? Ideally of course it should be possible to set out a strategic objective, and then to deliver the changes needed to get there. But if the change required is too great, or the barriers mean change is brought about too slowly, the short-term decisions of evolution may shape the future without regard to management intentions. That does not necessarily make the outcome worse in the greater scheme of things: after all, evolution is about survival of the fittest. But natural selection is an overwhelming force, and if short-term decisions are threatening to de-rail management’s strategic plan, it may be wise to take another look at the plan, and to try to work with evolution rather than against it.

Tyrannosaurus rex, Palais de la Découverte, Paris (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

Evolution is the natural process by which all forms of life adapt to changes in their environment. It is a very slow process, in which many small changes gradually accumulate. It is unplanned and undirected: who knows how the environment may change in the future, and so what adaptations would put us ahead of the game? Successful changes are not necessarily the best possible choices, merely the best of those that were tested. Different individuals start from different places, and so the adaptations which seem to work will vary. Consequently, over time, divergence will occur until different species result, even though each species can be traced back to a common ancestor. But evolution is brutal too: not all species will make it. Some find they have gone down an evolutionary dead end, and some that change is simply too fast for them to adapt to.

Sometimes organisational change can be like this. I once worked for a public-sector organisation which was privatised, so that it had to change from being ‘mission-led’ to being profit-led. Management set out a vision for what it wanted the organisation to become – essentially a similar, unitary, organisation but in the private sector – but was unable to make the radical changes necessary to deliver it fast enough. Evolution carried on regardless as the primary need to survive forced short-term decisions which deviated from the vision. Without a unifying mission as a common guide, different parts of the organisation evolved in different ways to adapt to their own local environments. Fragmentation followed, with a variety of different destinies for the parts, and a few divisions falling by the wayside. Despite starting down their preferred route of unitary privatisation, the eventual destination was exactly what the original managers had been determined to avoid.

What is the lesson? Ideally of course it should be possible to set out a strategic objective, and then to deliver the changes needed to get there. But if the change required is too great, or the barriers mean change is brought about too slowly, the short-term decisions of evolution may shape the future without regard to management intentions. That does not necessarily make the outcome worse in the greater scheme of things: after all, evolution is about survival of the fittest. But natural selection is an overwhelming force, and if short-term decisions are threatening to de-rail management’s strategic plan, it may be wise to take another look at the plan, and to try to work with evolution rather than against it.

Tyrannosaurus rex, Palais de la Découverte, Paris (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

Evolution is the natural process by which all forms of life adapt to changes in their environment. It is a very slow process, in which many small changes gradually accumulate. It is unplanned and undirected: who knows how the environment may change in the future, and so what adaptations would put us ahead of the game? Successful changes are not necessarily the best possible choices, merely the best of those that were tested. Different individuals start from different places, and so the adaptations which seem to work will vary. Consequently, over time, divergence will occur until different species result, even though each species can be traced back to a common ancestor. But evolution is brutal too: not all species will make it. Some find they have gone down an evolutionary dead end, and some that change is simply too fast for them to adapt to.

Sometimes organisational change can be like this. I once worked for a public-sector organisation which was privatised, so that it had to change from being ‘mission-led’ to being profit-led. Management set out a vision for what it wanted the organisation to become – essentially a similar, unitary, organisation but in the private sector – but was unable to make the radical changes necessary to deliver it fast enough. Evolution carried on regardless as the primary need to survive forced short-term decisions which deviated from the vision. Without a unifying mission as a common guide, different parts of the organisation evolved in different ways to adapt to their own local environments. Fragmentation followed, with a variety of different destinies for the parts, and a few divisions falling by the wayside. Despite starting down their preferred route of unitary privatisation, the eventual destination was exactly what the original managers had been determined to avoid.

What is the lesson? Ideally of course it should be possible to set out a strategic objective, and then to deliver the changes needed to get there. But if the change required is too great, or the barriers mean change is brought about too slowly, the short-term decisions of evolution may shape the future without regard to management intentions. That does not necessarily make the outcome worse in the greater scheme of things: after all, evolution is about survival of the fittest. But natural selection is an overwhelming force, and if short-term decisions are threatening to de-rail management’s strategic plan, it may be wise to take another look at the plan, and to try to work with evolution rather than against it.  How often have you found yourself having a conversation, and it gradually dawning on you that the person you are talking to thinks the conversation is about something quite different to what you thought? It happens to us all from time to time, and normally it causes at worst mild embarrassment as one of you says, ‘hang on a minute, I thought we were talking about x’ and the other looks bemused. Sometimes though, miscommunication can cause real problems.

How often have you found yourself having a conversation, and it gradually dawning on you that the person you are talking to thinks the conversation is about something quite different to what you thought? It happens to us all from time to time, and normally it causes at worst mild embarrassment as one of you says, ‘hang on a minute, I thought we were talking about x’ and the other looks bemused. Sometimes though, miscommunication can cause real problems.

E-mail Fireworks

Perhaps the most common place for miscommunication to cause problems in the working world is in e-mails. Maybe the relationship is a bit sticky already, or perhaps the subject is emotive. You write an e-mail, for example telling someone what you are going to do. Writing the message down gives you a chance to choose the words carefully so that they can’t be misinterpreted, right? Wrong! Within a few microseconds of pressing the ”send” button, you notice that your computer has started to smoke from the heat in the reply that has just clanged into your inbox. You read it – how could they have misunderstood your intentions so wildly? They must be spoiling for a fight! Your emotion finds its way into your reply, and the exchange just escalates. E-mail fireworks are never productive. Why are e-mails so fraught? Mainly, they are too easy. We dash them off with little thought. For straightforward factual messages that is not a problem. The trouble comes when the exchange has some (often unexpected) emotional content. Although they seem like a way of keeping the emotion out and so appear to be an easy option, humans are emotional creatures: we don’t often do purely rational. Be especially careful when you are worried about the reaction, and it feels safer to keep your distance. By omitting the emotional context of the message, which we detect mostly from body language and tone of voice, we take away the very cues which would help the recipient to know whether we meant to be provocative or were just not choosing our words very well. Poorly-chosen words in the context of a friendly tone and an open expression will usually only prompt clarification, but without these, people usually assume the worst. Here are five tips for minimising the risk of e-mail fireworks, and getting things back on track if necessary:- If you think the message might have some emotional content, don’t rely on e-mail if you can possibly avoid it. Start the exchange face-to-face, or at least with a phone call, so that there is an emotional context. Only once the tone has been set should you follow it up with an email.

- If you didn’t think the message was emotional, but the response appears to be – or even just indicates misunderstanding - never send an email reply. Pick up the phone straight away to clarify, or go and see them if you can.

- If you have to send an email which you know may be emotive, save a draft overnight before sending it, and re-read it in the morning. You have a better chance then of seeing how someone else might mis-interpret your words, and stopping it before it is too late. I rarely find I change nothing the next day!

- For really sensitive messages which you have to put in writing, ask someone else to check your words before you send them.

- If an exchange has gone emotional, apologise face to face – even if you don’t think you have anything to apologise for.

[caption id="" align="alignright" width="300"] Wing mirror VW Fox (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

Last week I had to drive my daughter to France to start a year of study at a French University. As you can imagine, the (small) car was packed to the roof with all the things she needed, or at least believed she needed, and which could not possibly get there any other way. Result – the rear view mirror only gave me a view of some pillows, which was not a lot of help. However, I very quickly adjusted to relying entirely on the wing mirrors, and felt reasonably safe even though I was driving on the ‘wrong’ side of the road.

The strange thing was that on the return journey, having unloaded in Nantes, I continued in the same way. It was only chance that I glanced in the direction of the main mirror, and realised that it was (of course) no longer obstructed. Information inertia!

Wing mirror VW Fox (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

Last week I had to drive my daughter to France to start a year of study at a French University. As you can imagine, the (small) car was packed to the roof with all the things she needed, or at least believed she needed, and which could not possibly get there any other way. Result – the rear view mirror only gave me a view of some pillows, which was not a lot of help. However, I very quickly adjusted to relying entirely on the wing mirrors, and felt reasonably safe even though I was driving on the ‘wrong’ side of the road.

The strange thing was that on the return journey, having unloaded in Nantes, I continued in the same way. It was only chance that I glanced in the direction of the main mirror, and realised that it was (of course) no longer obstructed. Information inertia!

Wing mirror VW Fox (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

Last week I had to drive my daughter to France to start a year of study at a French University. As you can imagine, the (small) car was packed to the roof with all the things she needed, or at least believed she needed, and which could not possibly get there any other way. Result – the rear view mirror only gave me a view of some pillows, which was not a lot of help. However, I very quickly adjusted to relying entirely on the wing mirrors, and felt reasonably safe even though I was driving on the ‘wrong’ side of the road.

The strange thing was that on the return journey, having unloaded in Nantes, I continued in the same way. It was only chance that I glanced in the direction of the main mirror, and realised that it was (of course) no longer obstructed. Information inertia!

Wing mirror VW Fox (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

Last week I had to drive my daughter to France to start a year of study at a French University. As you can imagine, the (small) car was packed to the roof with all the things she needed, or at least believed she needed, and which could not possibly get there any other way. Result – the rear view mirror only gave me a view of some pillows, which was not a lot of help. However, I very quickly adjusted to relying entirely on the wing mirrors, and felt reasonably safe even though I was driving on the ‘wrong’ side of the road.

The strange thing was that on the return journey, having unloaded in Nantes, I continued in the same way. It was only chance that I glanced in the direction of the main mirror, and realised that it was (of course) no longer obstructed. Information inertia!

Information inertia

Businesses need to rely more on looking forwards than looking back (as do drivers!) but the lesson for me was how easy it is to continue to rely on the kind of information which we have become used to, even when better information becomes available – and even when you really should know it is there. Of course it is comforting to have the same monthly report format that you have always had. You know exactly what information will be there, and where to find it. There is always a cost-benefit question around extra information, and it certainly needs to earn its keep. Nonetheless, it is a good idea to ask yourselves regularly whether there is any new information which should be added.

[caption id="" align="alignright" width="300"] Queueing for the Proms 2008 on the south steps of the Royal Albert Hall (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

I’m sitting on the steps outside the Royal Albert Hall in London. Fortunately today it isn’t raining, but even if it was, I needn’t worry. These days the Proms have an excellent system for managing the queue – rather like the ones on the deli counters in supermarkets. When you arrive, you are given a numbered ticket, which guarantees your place in the queue. Once you have your ticket, you can wander off for a coffee or a snack, or take shelter if it rains, knowing that everyone will be admitted in the order they joined the queue regardless. It is not particularly sophisticated – but it is a simple system, and it works.

Simplicity is hard-fought-for: it does not happen by accident. Once a complex process or system is in place, changing it to remove unnecessary complexity is hard, just as all change is. Even stopping a simple system getting more complicated needs constant vigilance: otherwise, it is likely to gather exceptions and special cases, as well as extra checks that seem important, but which have a cost which is frequently overlooked. Just as nature dictates that the disorder of the Universe (or a teenager’s bedroom) increases with time, and that this can only be reversed by the input of work, so it is with organisations.

Why does it matter? Because a simple system is inherently more efficient and less error-prone. Have you tried to explain your organisation’s processes to a new joiner? If so, how easy do you find it to explain the judgements required if the process has branches (if this, then that, but if not, then the other), and how quickly do people learn to make them properly? Good governance depends on people following the rules. Complexity makes it more likely that people will make mistakes, and also makes it harder to spot when people deliberately try to get round rules. For an extreme example of what happens with complexity, think about tax codes: with complex rules and many special cases, expert advisers earn a good living, which must be at the expense of either the tax-payer or the tax-collector or both. While that is good for the experts, does that not make its complexity bad for the rest of us?

Queueing for the Proms 2008 on the south steps of the Royal Albert Hall (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

I’m sitting on the steps outside the Royal Albert Hall in London. Fortunately today it isn’t raining, but even if it was, I needn’t worry. These days the Proms have an excellent system for managing the queue – rather like the ones on the deli counters in supermarkets. When you arrive, you are given a numbered ticket, which guarantees your place in the queue. Once you have your ticket, you can wander off for a coffee or a snack, or take shelter if it rains, knowing that everyone will be admitted in the order they joined the queue regardless. It is not particularly sophisticated – but it is a simple system, and it works.

Simplicity is hard-fought-for: it does not happen by accident. Once a complex process or system is in place, changing it to remove unnecessary complexity is hard, just as all change is. Even stopping a simple system getting more complicated needs constant vigilance: otherwise, it is likely to gather exceptions and special cases, as well as extra checks that seem important, but which have a cost which is frequently overlooked. Just as nature dictates that the disorder of the Universe (or a teenager’s bedroom) increases with time, and that this can only be reversed by the input of work, so it is with organisations.

Why does it matter? Because a simple system is inherently more efficient and less error-prone. Have you tried to explain your organisation’s processes to a new joiner? If so, how easy do you find it to explain the judgements required if the process has branches (if this, then that, but if not, then the other), and how quickly do people learn to make them properly? Good governance depends on people following the rules. Complexity makes it more likely that people will make mistakes, and also makes it harder to spot when people deliberately try to get round rules. For an extreme example of what happens with complexity, think about tax codes: with complex rules and many special cases, expert advisers earn a good living, which must be at the expense of either the tax-payer or the tax-collector or both. While that is good for the experts, does that not make its complexity bad for the rest of us?

Queueing for the Proms 2008 on the south steps of the Royal Albert Hall (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

I’m sitting on the steps outside the Royal Albert Hall in London. Fortunately today it isn’t raining, but even if it was, I needn’t worry. These days the Proms have an excellent system for managing the queue – rather like the ones on the deli counters in supermarkets. When you arrive, you are given a numbered ticket, which guarantees your place in the queue. Once you have your ticket, you can wander off for a coffee or a snack, or take shelter if it rains, knowing that everyone will be admitted in the order they joined the queue regardless. It is not particularly sophisticated – but it is a simple system, and it works.

Simplicity is hard-fought-for: it does not happen by accident. Once a complex process or system is in place, changing it to remove unnecessary complexity is hard, just as all change is. Even stopping a simple system getting more complicated needs constant vigilance: otherwise, it is likely to gather exceptions and special cases, as well as extra checks that seem important, but which have a cost which is frequently overlooked. Just as nature dictates that the disorder of the Universe (or a teenager’s bedroom) increases with time, and that this can only be reversed by the input of work, so it is with organisations.

Why does it matter? Because a simple system is inherently more efficient and less error-prone. Have you tried to explain your organisation’s processes to a new joiner? If so, how easy do you find it to explain the judgements required if the process has branches (if this, then that, but if not, then the other), and how quickly do people learn to make them properly? Good governance depends on people following the rules. Complexity makes it more likely that people will make mistakes, and also makes it harder to spot when people deliberately try to get round rules. For an extreme example of what happens with complexity, think about tax codes: with complex rules and many special cases, expert advisers earn a good living, which must be at the expense of either the tax-payer or the tax-collector or both. While that is good for the experts, does that not make its complexity bad for the rest of us?

Queueing for the Proms 2008 on the south steps of the Royal Albert Hall (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

I’m sitting on the steps outside the Royal Albert Hall in London. Fortunately today it isn’t raining, but even if it was, I needn’t worry. These days the Proms have an excellent system for managing the queue – rather like the ones on the deli counters in supermarkets. When you arrive, you are given a numbered ticket, which guarantees your place in the queue. Once you have your ticket, you can wander off for a coffee or a snack, or take shelter if it rains, knowing that everyone will be admitted in the order they joined the queue regardless. It is not particularly sophisticated – but it is a simple system, and it works.

Simplicity is hard-fought-for: it does not happen by accident. Once a complex process or system is in place, changing it to remove unnecessary complexity is hard, just as all change is. Even stopping a simple system getting more complicated needs constant vigilance: otherwise, it is likely to gather exceptions and special cases, as well as extra checks that seem important, but which have a cost which is frequently overlooked. Just as nature dictates that the disorder of the Universe (or a teenager’s bedroom) increases with time, and that this can only be reversed by the input of work, so it is with organisations.

Why does it matter? Because a simple system is inherently more efficient and less error-prone. Have you tried to explain your organisation’s processes to a new joiner? If so, how easy do you find it to explain the judgements required if the process has branches (if this, then that, but if not, then the other), and how quickly do people learn to make them properly? Good governance depends on people following the rules. Complexity makes it more likely that people will make mistakes, and also makes it harder to spot when people deliberately try to get round rules. For an extreme example of what happens with complexity, think about tax codes: with complex rules and many special cases, expert advisers earn a good living, which must be at the expense of either the tax-payer or the tax-collector or both. While that is good for the experts, does that not make its complexity bad for the rest of us?  A few years ago I needed to hire an assistant. I’d fixed an interview, and everything was organised. It was five minutes before the time the candidate was due, and I was just collecting my papers and my thoughts. At that moment, the din of the fire alarm started up.

There is – of course – nothing that you can do. Down the concrete back stairs, and out round the back of the building to the assembly point, into the London drizzle without a coat, while I imagined my interviewee arriving at the front. I had left all my papers on my desk in the dry, and had no other record of his contact details, so I had no way to suggest an alternative plan.

A little while later, my mobile rang. Having arrived and been barred from entry, he had managed to track down my mobile number himself, and we were able to arrange to carry on with the interview while we dried out in a local coffee shop. Needless to say, his resourcefulness impressed me and he got the job. Despite the unhelpful circumstances of the interview, he was one of my best hires ever.

Life has a habit of not going the way we plan it. Unexpected circumstances can often be turned to our advantage though, if we grasp them rather than trying to stick to the plan, and often the results are better than you could possibly have expected.

A few years ago I needed to hire an assistant. I’d fixed an interview, and everything was organised. It was five minutes before the time the candidate was due, and I was just collecting my papers and my thoughts. At that moment, the din of the fire alarm started up.

There is – of course – nothing that you can do. Down the concrete back stairs, and out round the back of the building to the assembly point, into the London drizzle without a coat, while I imagined my interviewee arriving at the front. I had left all my papers on my desk in the dry, and had no other record of his contact details, so I had no way to suggest an alternative plan.

A little while later, my mobile rang. Having arrived and been barred from entry, he had managed to track down my mobile number himself, and we were able to arrange to carry on with the interview while we dried out in a local coffee shop. Needless to say, his resourcefulness impressed me and he got the job. Despite the unhelpful circumstances of the interview, he was one of my best hires ever.

Life has a habit of not going the way we plan it. Unexpected circumstances can often be turned to our advantage though, if we grasp them rather than trying to stick to the plan, and often the results are better than you could possibly have expected.

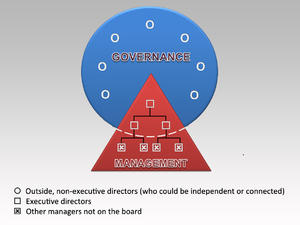

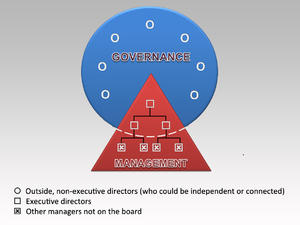

[caption id="" align="alignright" width="300"] English: Corporate Governance (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

All organisations have to find an appropriate balance between central control and local freedom to act. Governance provides the framework and checks and balances within which this is established and managed. It ensures that the process by which decisions are made is appropriately managed. It allows them to be seen to have been taken in the best interests of the shareholders, taking account of all the demands on the organisation, the risks, and the information available at the time.

English: Corporate Governance (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

All organisations have to find an appropriate balance between central control and local freedom to act. Governance provides the framework and checks and balances within which this is established and managed. It ensures that the process by which decisions are made is appropriately managed. It allows them to be seen to have been taken in the best interests of the shareholders, taking account of all the demands on the organisation, the risks, and the information available at the time.

English: Corporate Governance (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

All organisations have to find an appropriate balance between central control and local freedom to act. Governance provides the framework and checks and balances within which this is established and managed. It ensures that the process by which decisions are made is appropriately managed. It allows them to be seen to have been taken in the best interests of the shareholders, taking account of all the demands on the organisation, the risks, and the information available at the time.

English: Corporate Governance (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

All organisations have to find an appropriate balance between central control and local freedom to act. Governance provides the framework and checks and balances within which this is established and managed. It ensures that the process by which decisions are made is appropriately managed. It allows them to be seen to have been taken in the best interests of the shareholders, taking account of all the demands on the organisation, the risks, and the information available at the time.

Review your governance

If several of the following statements are true of your organisation, it may well be a good idea to review your governance arrangements.- The governance structure (meetings and delegations) does not constitute a simple hierarchy underneath the Board, with clear parent-child relationships and information cascaded up and down the hierarchy

- The governance structure is not clearly documented (e.g. including a consistent set of Terms of Reference), communicated and understood

- People do not have clear written instructions as to the limits of the authority that they have been given, or these are ignored

- Committees are allowed to approve their own Terms of Reference and/or memberships

- Governance meetings happen irregularly, or with papers which are poor quality or issued late

- Senior staff are allowed to ignore the rules which apply to others

- Decisions are often taken late because of papers missing submission dates, inadequate information, wrong attendance, submission to the wrong meeting, unexpected need for escalation, etc

- There is a feeling that the governance process is too bureaucratic