Just before Christmas, I was doing some last-minute shopping in one of the Oxford Street department stores. As usual at that time of year, there was a long queue for the checkouts. When I eventually got to a till, I was surprised to see two people there. There was a young man operating the till. And there was a tall older man bagging the goods sold. Although they were busy, you could tell that they were working well together, and enjoying exchanging a few words with customers and each other when they could.

Despite this, the older man had a gravitas that you associate more with the Board room than with the tills of a busy store. Not surprising really – he was a senior manager doing a shift supporting the front-line staff at their busiest time. What was surprising (apart from him being there at all) was the easy way he appeared to be accepted as part of the team.

Here was a real “one-team” culture in action. He was not just doing what the organisation expected. He was doing what he believed in, and so it came naturally. His colleagues saw it as perfectly natural and normal too. Everyone was comfortable, and it worked.

Culture is the pattern of behaviours that people adopt in order to be accepted in a community. It is defined by what people really value, not what they say they value. In that store, people really valued working together as one team to deliver happy customers. That meant that there was nothing awkward about managers working on the tills. Actions speak louder than words, and clearly it works for them.

Just before Christmas, I was doing some last-minute shopping in one of the Oxford Street department stores. As usual at that time of year, there was a long queue for the checkouts. When I eventually got to a till, I was surprised to see two people there. There was a young man operating the till. And there was a tall older man bagging the goods sold. Although they were busy, you could tell that they were working well together, and enjoying exchanging a few words with customers and each other when they could.

Despite this, the older man had a gravitas that you associate more with the Board room than with the tills of a busy store. Not surprising really – he was a senior manager doing a shift supporting the front-line staff at their busiest time. What was surprising (apart from him being there at all) was the easy way he appeared to be accepted as part of the team.

Here was a real “one-team” culture in action. He was not just doing what the organisation expected. He was doing what he believed in, and so it came naturally. His colleagues saw it as perfectly natural and normal too. Everyone was comfortable, and it worked.

Culture is the pattern of behaviours that people adopt in order to be accepted in a community. It is defined by what people really value, not what they say they value. In that store, people really valued working together as one team to deliver happy customers. That meant that there was nothing awkward about managers working on the tills. Actions speak louder than words, and clearly it works for them.

Walking the Talk

That experience prompted me to re-read Carolyn Taylor’s “Walking the Talk”, an excellent introduction to corporate culture. Here was an organisation that has a clearly-defined culture, and knows how to maintain it by walking the talk. Sadly, in my experience most leaders are better at the talking than the walking, and in any case most organisations don’t really know what culture they want (if they think about it at all). That’s a lot of value to be losing. As a professional change manager and consultant, I get asked to advise on how to bring about cultural change in organisations. Often, part of the conversation goes something like this:

“We really need to change how we do things. We just don’t have enough hours in the day to get everything done.”

“Yes, I can see that that would be a problem. I’m sure that there is a better way. It sounds like you need to delegate more. How comfortable are you with delegating to your managers?”

“That would be fine. But the problem is, our staff don’t have enough time for everything they need to do now either.”

“Hmm. You need a change programme – which you will need time and energy to lead – but you don’t have any spare capacity, and there is nowhere you can delegate stuff to free up some. So what parts of what you do now are you willing to see not being done at all to make the change happen?”

That often produces blank looks. But you have to devote time to leading change if you want it to succeed. You also have to lead by example. You have to demonstrate that change is a sufficiently high priority for you that it displaces other things. Other people are unlikely to change what they do until they see you changing what you spend time on, not just talking about doing so.

As a professional change manager and consultant, I get asked to advise on how to bring about cultural change in organisations. Often, part of the conversation goes something like this:

“We really need to change how we do things. We just don’t have enough hours in the day to get everything done.”

“Yes, I can see that that would be a problem. I’m sure that there is a better way. It sounds like you need to delegate more. How comfortable are you with delegating to your managers?”

“That would be fine. But the problem is, our staff don’t have enough time for everything they need to do now either.”

“Hmm. You need a change programme – which you will need time and energy to lead – but you don’t have any spare capacity, and there is nowhere you can delegate stuff to free up some. So what parts of what you do now are you willing to see not being done at all to make the change happen?”

That often produces blank looks. But you have to devote time to leading change if you want it to succeed. You also have to lead by example. You have to demonstrate that change is a sufficiently high priority for you that it displaces other things. Other people are unlikely to change what they do until they see you changing what you spend time on, not just talking about doing so.

Change needs time

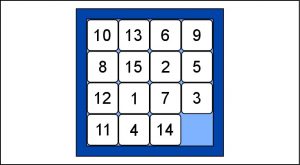

Think of it like a sliding-tile puzzle. In a 4 x 4 puzzle there are 15 tiles, so that there is always one space to move the next tile into. That gives enough flexibility to rearrange all the tiles into the right pattern. If there were 16 tiles – completely filling the frame – nothing could move at all. You have to find an empty space in your time, like the missing tile, to be able to rearrange your organisational tiles. Like many things in life, this is just about priorities. If change is high enough up your priority list, it will displace other activities to create the necessary space. If it isn’t, it is best not to start. This seasonal message will help you to remember!

Last week I attended the inaugural meeting of the Change Management Institute’s Thought Leadership Panel. Getting a group of senior practitioners together is always interesting. I’m sure that if we hadn’t all had other things to do the conversation could have gone on a long time!

I have been thinking some more about two related questions which we didn’t have time to explore very far. What makes a change manager? And why do so many senior leaders struggle to ‘get’ how change management works?

Perhaps the best starting point for thinking about what makes a change manager is to look at people who are change managers and consider how they got there. The first thing that is clear is that they come from a wide variety of different backgrounds. Indeed, many change managers have done a wide variety of different things in their careers. That was certainly true of those present last week. All of that suggests that there is no standard model. A good change leader probably takes advantage of having a wide variety of experience and examples to draw on - stories to tell, if you will. Where those experiences come from is less important.

Then there is a tension between two different kinds of approach. Change managers have to be project managers to get things done. But change is not like most projects: there is a limit to how far you can push the pace (and still have the change stick) because that depends on changing the mindsets of people affected. Thumping the table or throwing money at it hardly ever speeds that up. Successful change managers moderate the push for quick results with a sensitivity to how those people are reacting. Not all project managers can do that.

So I think you need three main ingredients for a successful change leader:

- The analytical and planning skills to manage projects;

- The people skills to listen and to influence and manage accordingly;

- Enough varied experiences to draw on to be able to tell helpful stories from similar situations.

Senior managers and change

Why do many senior managers struggle to understand the change process? They may well have the same basic skills, but the blending is usually more focused on results than on process. That is not surprising; their jobs depend on delivering results. A pure ‘results’ focus may be OK to run a stable operation. Problems are likely to arise when change is required if the process component is too limited. Delivering change successfully usually depends on the senior managers as well as the change manager understanding that difference. As an interim manager, I rely on networks to find my next assignment. Many of the people in my immediate network I have known for years, but I still make sure I keep in touch. It only needs the occasional coffee, phone call or email. With newer contacts that I know less well, I make more effort to build the relationship.

Most of those people will never give me any work. It is not that they don’t want to, but possible assignments depend on relevant needs coming up. From a hard-nosed point of view, as an investment perhaps my effort is not worth it. But I keep in touch because I want to maintain the relationships, not because they might lead to work. I believe that the willingness to meet would soon dry up if people felt I was only there to sell.

I spend quite a lot of my free time supporting my University’s alumni relations. We all know that in the end there is only one reason why universities have become so keen on keeping in touch with alumni recently. They want our money.

However, donations do not just happen. Unless there is an overt exchange (e.g. we will name xxx after you in return), persuading people to give depends on the relationship you have with them. And relationships are really between people, not between people and organisations. I build relationships with fellow alumni through activities we share only because I – and they – value the relationships themselves. If that builds engagement with the University and leads to giving, that’s good, but it is never the point. Indeed, raising the subject of fundraising at all would put some people off engaging, so it is off-limits.

As an interim manager, I rely on networks to find my next assignment. Many of the people in my immediate network I have known for years, but I still make sure I keep in touch. It only needs the occasional coffee, phone call or email. With newer contacts that I know less well, I make more effort to build the relationship.

Most of those people will never give me any work. It is not that they don’t want to, but possible assignments depend on relevant needs coming up. From a hard-nosed point of view, as an investment perhaps my effort is not worth it. But I keep in touch because I want to maintain the relationships, not because they might lead to work. I believe that the willingness to meet would soon dry up if people felt I was only there to sell.

I spend quite a lot of my free time supporting my University’s alumni relations. We all know that in the end there is only one reason why universities have become so keen on keeping in touch with alumni recently. They want our money.

However, donations do not just happen. Unless there is an overt exchange (e.g. we will name xxx after you in return), persuading people to give depends on the relationship you have with them. And relationships are really between people, not between people and organisations. I build relationships with fellow alumni through activities we share only because I – and they – value the relationships themselves. If that builds engagement with the University and leads to giving, that’s good, but it is never the point. Indeed, raising the subject of fundraising at all would put some people off engaging, so it is off-limits.

Relationship building sows seeds

The point of relationship building and maintaining networks is to create a fertile seed-bed for what you hope will germinate in the future. The gardener can dig the soil, add compost, and provide water. He can provide the conditions for successful germination. The miracle of germination though comes from the seeds themselves. I’ve just started trying to organise a local walking group for alumni from my university. The initial process was simple: I wrote an email asking for interest, the alumni office sent it out to people on their database with postcodes in the local area, and I collected the responses.

The outcome has been pleasantly surprising. The response rate was over 10%, which under almost any circumstances I would think was a fantastic return for a single ‘cold call’ message out of the blue. But almost as surprising was the proportion of responses which included words along the lines of ‘what a good idea’ with at least the implication of ‘why has no-one suggested this before?’. It seemed as if all that latent demand was just sitting there waiting to be tapped.

I’ve just started trying to organise a local walking group for alumni from my university. The initial process was simple: I wrote an email asking for interest, the alumni office sent it out to people on their database with postcodes in the local area, and I collected the responses.

The outcome has been pleasantly surprising. The response rate was over 10%, which under almost any circumstances I would think was a fantastic return for a single ‘cold call’ message out of the blue. But almost as surprising was the proportion of responses which included words along the lines of ‘what a good idea’ with at least the implication of ‘why has no-one suggested this before?’. It seemed as if all that latent demand was just sitting there waiting to be tapped.

Innovation

That set me thinking about how innovation happens. This was not a complicated idea; anyone could have tried it. But no one else did. So what does innovation need? I think there are usually two ingredients. The first is some kind of investment. Often that is financial, but (as in this case) it may just be time and emotional energy. Investment means that you have to put something in, but that success is uncertain and although you may be rewarded well, you may also get nothing back. So the innovator must be willing to take that risk. The second is some relevant knowledge. I had done something similar before, so I knew an easy way to reach my target audience. That knowledge reduced both my investment of time and the risk of failure I saw. I might have been willing to try anyway, but this made it more likely that I would. Certainly I was more likely to try than people without that knowledge. All of us prioritise what we will spend our time on, largely based on our perception of the risk-reward balances of our options. Making innovation happen is usually not about brilliant ideas; it is far more about simply taking the risk to put a simple idea into practice. There is little you can do to change someone’s appetite for risk. If you want to encourage innovation, then, try to find ways to reduce the risk that they see.

It was only in the latter stages of the referendum campaign that the penny dropped for me. I realised that the reason that the campaign was so much about emotion and so little about facts and likely consequences was that, whatever its ostensible purpose, the referendum had come to be about who we are. My identity is what I believe it to be, and what those I identify with believe it to be. The outcome of a referendum does not, cannot, change that, even if it can lead to a change of status.

It would obviously be nonsense if, when you asked someone whether they would be best off staying married or getting divorced, they stated their gender as the answer. Politicians have allowed a question about relationship to be given an answer about identity. Apples and oranges. In so doing they have shot themselves – and at the same time the whole country – in the foot.

How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

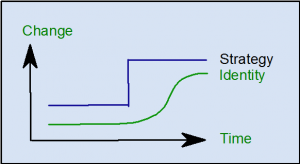

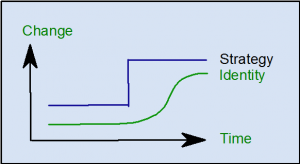

Identity and change

There is a profound lesson about change there. Identity is perhaps the ‘stickiest’ phenomenon in culture, because belonging is so fundamental to our sense of security. A change project is often perceived as changing in some way the identity of that to which we belong. However, peoples’ sense of identity changes much more slowly than the strategy. If we do not take steps to bridge the identity gap while people catch up, it is the relationship which is in for trouble. How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

Near where I live, there is a wonderful cheese shop. It sells an amazing selection of English artisanal cheeses, as well as a variety of other delicious local produce. Not surprisingly, it is my place of choice for cheese for Christmas. It's just a pity that the customer service is not up to the standard of the cheese.

I placed my order in good time, for collection on 23 December. I duly arrived at the shop, full of anticipation, on my way home from work. The table outside groaned with goodies including beautifully-decorated cakes, rustic breads and colourful preserves. The shop is fairly simple inside, but filled with the wonderful aroma from the cheeses and from the delicious food being served in their upstairs café.

There seemed only to be one young lady serving, and she looked a bit stressed by the queue of customers; cutting, weighing and wrapping cheeses is a slow process. Still, I assumed serving me would be easy – all that should have been done already. She looked in the fridges under the cool counter; not there. She looked in another fridge; no better. Looking more stressed, she told me that she was very sorry, she couldn’t find my order; “Would you mind going away and coming back later?”

Bad move. “Yes, actually, I would. I’m on my way home from work, I've had a busy day, and I don’t want to hang around. That’s why I placed an order.” Another hunt still produced nothing.

A small lady with shoulder-length reddish hair came in – the manager. We found where my order had been written in the book, just as I had said. “Well, if you can wait, we can make up some of your order again, but I’m afraid we have none of the Tamworth left. We are completely sold out of soft cheeses.” I grumpily agreed that they had better do that, meanwhile starting to wonder where I would be able to find a good soft cheese on Christmas Eve. Then she showed me a small cheese –under 100g I would say – and said “we have one of these left. They are absolutely delicious – unfortunately I can’t give you a taste as it is the last one. They are £6.” … So that is about £60 / kg? Are you serious? No thanks.

After that, the manager lost interest. The assistant worked out the total price, and only then said “we’ll give you 10% off for the inconvenience”. I paid, and walked out with my cheese, about 20 minutes later than I had expected and in a thoroughly bad temper.

So what did I learn from these unhappy events? Observing my own feelings, first, that the longer the problem lasts, the more it takes to put it right. And second, that if you don’t do enough, you might as well do nothing.

There you are, head down in a report, a spreadsheet, or some other urgent bit of business. There’s a knock, and your mind returns to your desk from miles away. Someone says they have a problem and can they talk it over with you please? An interruption. What are you going to say?

Your work is high-value, it takes real concentration, and you need to keep your focus to get it done right. On the other hand, if you send them away, you may be telling them that you do not value them and what they do.

Of course my own work seems urgent, but I know I’ll get it done one way or another. My colleague on the other hand is important, because it is essential for the longer term that they feel valued. I could easily – and quickly – damage a relationship I have taken a long time to build. I know they would not interrupt me when I’m busy unless they felt it was important. It is really important to give them something to show that I’m taking them seriously.

Even if I decide I can only spare 5 minutes now, I’ll always offer that as a first step, at least to give them things to be thinking about until I can pay full attention. If I give them proper respect, value them, take their problems seriously, I find that they respect me back – and interruption is rare unless it really is necessary.

So if you really can't deal with the interruption fully there and then, at least find some compromise. It will pay you back in the long run.

There you are, head down in a report, a spreadsheet, or some other urgent bit of business. There’s a knock, and your mind returns to your desk from miles away. Someone says they have a problem and can they talk it over with you please? An interruption. What are you going to say?

Your work is high-value, it takes real concentration, and you need to keep your focus to get it done right. On the other hand, if you send them away, you may be telling them that you do not value them and what they do.

Of course my own work seems urgent, but I know I’ll get it done one way or another. My colleague on the other hand is important, because it is essential for the longer term that they feel valued. I could easily – and quickly – damage a relationship I have taken a long time to build. I know they would not interrupt me when I’m busy unless they felt it was important. It is really important to give them something to show that I’m taking them seriously.

Even if I decide I can only spare 5 minutes now, I’ll always offer that as a first step, at least to give them things to be thinking about until I can pay full attention. If I give them proper respect, value them, take their problems seriously, I find that they respect me back – and interruption is rare unless it really is necessary.

So if you really can't deal with the interruption fully there and then, at least find some compromise. It will pay you back in the long run.  I have been reading

I have been reading