As a professional change manager and consultant, I get asked to advise on how to bring about cultural change in organisations. Often, part of the conversation goes something like this:

“We really need to change how we do things. We just don’t have enough hours in the day to get everything done.”

“Yes, I can see that that would be a problem. I’m sure that there is a better way. It sounds like you need to delegate more. How comfortable are you with delegating to your managers?”

“That would be fine. But the problem is, our staff don’t have enough time for everything they need to do now either.”

“Hmm. You need a change programme – which you will need time and energy to lead – but you don’t have any spare capacity, and there is nowhere you can delegate stuff to free up some. So what parts of what you do now are you willing to see not being done at all to make the change happen?”

That often produces blank looks. But you have to devote time to leading change if you want it to succeed. You also have to lead by example. You have to demonstrate that change is a sufficiently high priority for you that it displaces other things. Other people are unlikely to change what they do until they see you changing what you spend time on, not just talking about doing so.

As a professional change manager and consultant, I get asked to advise on how to bring about cultural change in organisations. Often, part of the conversation goes something like this:

“We really need to change how we do things. We just don’t have enough hours in the day to get everything done.”

“Yes, I can see that that would be a problem. I’m sure that there is a better way. It sounds like you need to delegate more. How comfortable are you with delegating to your managers?”

“That would be fine. But the problem is, our staff don’t have enough time for everything they need to do now either.”

“Hmm. You need a change programme – which you will need time and energy to lead – but you don’t have any spare capacity, and there is nowhere you can delegate stuff to free up some. So what parts of what you do now are you willing to see not being done at all to make the change happen?”

That often produces blank looks. But you have to devote time to leading change if you want it to succeed. You also have to lead by example. You have to demonstrate that change is a sufficiently high priority for you that it displaces other things. Other people are unlikely to change what they do until they see you changing what you spend time on, not just talking about doing so.

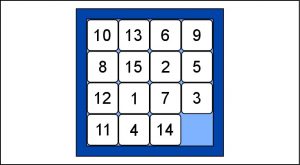

Change needs time

Think of it like a sliding-tile puzzle. In a 4 x 4 puzzle there are 15 tiles, so that there is always one space to move the next tile into. That gives enough flexibility to rearrange all the tiles into the right pattern. If there were 16 tiles – completely filling the frame – nothing could move at all. You have to find an empty space in your time, like the missing tile, to be able to rearrange your organisational tiles. Like many things in life, this is just about priorities. If change is high enough up your priority list, it will displace other activities to create the necessary space. If it isn’t, it is best not to start. This seasonal message will help you to remember!

Last week I attended the inaugural meeting of the Change Management Institute’s Thought Leadership Panel. Getting a group of senior practitioners together is always interesting. I’m sure that if we hadn’t all had other things to do the conversation could have gone on a long time!

I have been thinking some more about two related questions which we didn’t have time to explore very far. What makes a change manager? And why do so many senior leaders struggle to ‘get’ how change management works?

Perhaps the best starting point for thinking about what makes a change manager is to look at people who are change managers and consider how they got there. The first thing that is clear is that they come from a wide variety of different backgrounds. Indeed, many change managers have done a wide variety of different things in their careers. That was certainly true of those present last week. All of that suggests that there is no standard model. A good change leader probably takes advantage of having a wide variety of experience and examples to draw on - stories to tell, if you will. Where those experiences come from is less important.

Then there is a tension between two different kinds of approach. Change managers have to be project managers to get things done. But change is not like most projects: there is a limit to how far you can push the pace (and still have the change stick) because that depends on changing the mindsets of people affected. Thumping the table or throwing money at it hardly ever speeds that up. Successful change managers moderate the push for quick results with a sensitivity to how those people are reacting. Not all project managers can do that.

So I think you need three main ingredients for a successful change leader:

- The analytical and planning skills to manage projects;

- The people skills to listen and to influence and manage accordingly;

- Enough varied experiences to draw on to be able to tell helpful stories from similar situations.

Senior managers and change

Why do many senior managers struggle to understand the change process? They may well have the same basic skills, but the blending is usually more focused on results than on process. That is not surprising; their jobs depend on delivering results. A pure ‘results’ focus may be OK to run a stable operation. Problems are likely to arise when change is required if the process component is too limited. Delivering change successfully usually depends on the senior managers as well as the change manager understanding that difference. The other day I passed a set of temporary traffic lights. Hardly an unusual occurrence in a modern city! This was a nice modern set, with the lights made up of an array of LEDs. That is of course a great improvement. Apart from the environmental benefits of being low-energy and long-lasting, the light area is evenly bright all over. And there can be no problem with low sun reflecting off the back mirror so it is hard to tell which colour is illuminated.

What struck me, however, was that the LEDs were carefully arranged in a circular pattern, mimicking the traditional look of traffic lights. This is clearly not the most efficient way of arranging them. That would be a hexagonal pattern, but of course you cannot produce what looks like a neat circular outline that way.

There is no reason why in an LED system each colour of light has to be round. They could just as well be hexagonal, or any other convenient shape. A hexagon would clearly match a hexagonal pattern better. Indeed, there could be advantage in making each colour a different shape, to help the colour-blind. They make the lights round because that is how we expect traffic lights to look.

The other day I passed a set of temporary traffic lights. Hardly an unusual occurrence in a modern city! This was a nice modern set, with the lights made up of an array of LEDs. That is of course a great improvement. Apart from the environmental benefits of being low-energy and long-lasting, the light area is evenly bright all over. And there can be no problem with low sun reflecting off the back mirror so it is hard to tell which colour is illuminated.

What struck me, however, was that the LEDs were carefully arranged in a circular pattern, mimicking the traditional look of traffic lights. This is clearly not the most efficient way of arranging them. That would be a hexagonal pattern, but of course you cannot produce what looks like a neat circular outline that way.

There is no reason why in an LED system each colour of light has to be round. They could just as well be hexagonal, or any other convenient shape. A hexagon would clearly match a hexagonal pattern better. Indeed, there could be advantage in making each colour a different shape, to help the colour-blind. They make the lights round because that is how we expect traffic lights to look.

Features that get overlooked

When looking at business improvements, there are usually aspects of the status quo which we retain and aspects which we decide to change. Some features are like the colours of traffic lights. The confusion caused by changing them would a serious problem, and we know we must not. Others may be like the type of light source. It is obvious that a change is possible if it is beneficial. However, some are like the shape of lights, which we are so used to that we forget to challenge them. We always need to be on the lookout for features kept because we forgot they could be changed rather than for good reason.

It was only in the latter stages of the referendum campaign that the penny dropped for me. I realised that the reason that the campaign was so much about emotion and so little about facts and likely consequences was that, whatever its ostensible purpose, the referendum had come to be about who we are. My identity is what I believe it to be, and what those I identify with believe it to be. The outcome of a referendum does not, cannot, change that, even if it can lead to a change of status.

It would obviously be nonsense if, when you asked someone whether they would be best off staying married or getting divorced, they stated their gender as the answer. Politicians have allowed a question about relationship to be given an answer about identity. Apples and oranges. In so doing they have shot themselves – and at the same time the whole country – in the foot.

How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

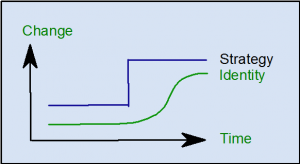

Identity and change

There is a profound lesson about change there. Identity is perhaps the ‘stickiest’ phenomenon in culture, because belonging is so fundamental to our sense of security. A change project is often perceived as changing in some way the identity of that to which we belong. However, peoples’ sense of identity changes much more slowly than the strategy. If we do not take steps to bridge the identity gap while people catch up, it is the relationship which is in for trouble. How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

I’ve been working in a public sector organisation recently, trying to introduce some practices that are normal in the private sector. Change in the public sector is not necessarily harder than in the private sector, but it has some distinct challenges - notably a lack of carrots, and few sticks!

As well as a general lack of experience with project management discipline, I have experienced two particular (related) frustrations.

The first is a lack of urgency. There is no sense that it much matters whether the changes are delivered at the time promised (or perhaps at all!). I think that stems partly from the observation that most other change projects people see or hear about either fail to complete on time, or fail to do so in a way that sticks. Why is that? An apparent absence of material consequences for failing to keep promises can’t help. With no sticks, only carrots are left, and carrots of any size are also hard to find in the public sector.

The second lack – which I think stems partly from the first, and partly from wider public sector culture – is a lack of emotional engagement. Meaningful and significant carrots and sticks can create motivation, but so can a simple belief that “it” is the right thing to do. In a mission-led organisation, it is all too easy for staff to believe that any change is a threat to the mission, and so, far from being right, it must be the “wrong” thing to do: whatever passion there is is pulling in the wrong direction.

There are no easy answers, but perseverance and patience are an essential start. I think that in such organisations, real change is almost inevitably slow. As always with change, a key is to look for “what’s in it for them”, and in the public sector fewer options are available so this requires more imagination. To start with, I try to look for subjects which arouse some passion in staff (things that get in the way of delivering their “mission” so that our objectives are aligned, or which cause them frustration and aggravation, for instance) – and build on those.

If only it were quicker!

Walking along Blackfriars Road in London the other day, I realised that there was something odd about the very ordinary building I was passing. I must have walked past it quite a few times before, perhaps thinking about something else, perhaps looking the other way, perhaps just being unobservant – but this was the first time I had noticed.

How often are we so conditioned by what we expect to see that, so long as it more or less conforms to the norm, we build the oddities into our prevailing view rather than seeing things from a new perspective (curved window sills? A bit odd, maybe, but architects like to try out different ideas)? Change is difficult to implement, but the biggest problem is often getting started in the first place because people find it very hard to change the way they look at the issue, and so can’t see the need for a radical re-think. Another visual parallel is photographs of things like moon craters – do they go in or do they go out? Once you see it one way, it is hard to see it the other.

As a change agent, part of my job is to help people to see issues from a new perspective, and then to see that that new perspective leads to a new and better way of organising the response. If there is no new perspective, there is nothing to justify the change, and it is easy to see why people would choose to carry on as before.

If you still haven’t got it, look at http://www.london-se1.co.uk/news/view/7248 - or just try looking at the picture upside-down!

[contact-form][contact-field label='Name' type='name' required='1'/][contact-field label='Email' type='email' required='1'/][contact-field label='Website' type='url'/][contact-field label='Comment' type='textarea' required='1'/][/contact-form]

Walking along Blackfriars Road in London the other day, I realised that there was something odd about the very ordinary building I was passing. I must have walked past it quite a few times before, perhaps thinking about something else, perhaps looking the other way, perhaps just being unobservant – but this was the first time I had noticed.

How often are we so conditioned by what we expect to see that, so long as it more or less conforms to the norm, we build the oddities into our prevailing view rather than seeing things from a new perspective (curved window sills? A bit odd, maybe, but architects like to try out different ideas)? Change is difficult to implement, but the biggest problem is often getting started in the first place because people find it very hard to change the way they look at the issue, and so can’t see the need for a radical re-think. Another visual parallel is photographs of things like moon craters – do they go in or do they go out? Once you see it one way, it is hard to see it the other.

As a change agent, part of my job is to help people to see issues from a new perspective, and then to see that that new perspective leads to a new and better way of organising the response. If there is no new perspective, there is nothing to justify the change, and it is easy to see why people would choose to carry on as before.

If you still haven’t got it, look at http://www.london-se1.co.uk/news/view/7248 - or just try looking at the picture upside-down!

[contact-form][contact-field label='Name' type='name' required='1'/][contact-field label='Email' type='email' required='1'/][contact-field label='Website' type='url'/][contact-field label='Comment' type='textarea' required='1'/][/contact-form]

I’ve recently started taking singing lessons. A bit late, you might say, since I have been singing in choirs for decades, and I certainly wish I’d started sooner. But it has taught me something important about how we learn.

I have been surprised to discover that almost none of my lesson time is about singing in tune or in time! Everything is about technique – how you breath, how you pronounce the words – and a lot of my practice is just saying the words, not singing them at all. It is really hard to train your body to work in a very particular way: months or years of lessons, hours and hours of practice. You can’t just be told the right way to do it, and go away and then do it right - it is more like learning to drive than learning to pass an academic exam. And sometimes you have to be told something over and over again before you are ready to absorb it.

I have taken away three wider lessons:

• What you have to do to learn a new skill may be quite different from what you expected;

• Results may take a long time and demand considerable perseverance; there are no short-cuts;

• Hearing something is not enough – you have to hear it at the right time.

That has made me think about the problems of change in a different way. As an example, one of my clients has many junior and middle managers with a fairly low level of financial understanding, and with commercial pressure continually increasing this is holding them back. How should we fix this? The traditional approach would probably be to send them on a short course to learn the “facts” about finance – understanding a P&L, a balance sheet, etc. But perhaps it is not the facts but the practice they are short of, or they are not ready to hear the message? I have done enough short courses myself to know that few of the facts stay in the mind for long anyway. The singing lessons experience suggests to me that they are probably only part of the solution.

Time to think about a new approach, based on how we learn!

A couple of weeks ago, I had an evening out at the opera. I’d never encountered this on previous visits, but throughout the performance, there was a lady at the side of the stage translating the sung words into sign language. At the time I thought it rather odd – why would deaf people come to the opera at all? In any case, the words were displayed in English text over the top of the stage. Was this accessibility gone mad?

That prompted me to do a little research, and to realise that there are many reasons why there might be deaf people in the audience: from the obvious-if-you-think-about-it possibility that they might be with partners who are not deaf, to the much more important facts that most deaf people have some hearing and may well enjoy music (and even if they have no hearing, may find musical enjoyment in feeling the vibrations), and the more profound realisation that for some deaf people the English spoken and written around them may be ‘foreign’ compared to sign language.