A couple of weeks ago, I had an evening out at the opera. I’d never encountered this on previous visits, but throughout the performance, there was a lady at the side of the stage translating the sung words into sign language. At the time I thought it rather odd – why would deaf people come to the opera at all? In any case, the words were displayed in English text over the top of the stage. Was this accessibility gone mad?

That prompted me to do a little research, and to realise that there are many reasons why there might be deaf people in the audience: from the obvious-if-you-think-about-it possibility that they might be with partners who are not deaf, to the much more important facts that most deaf people have some hearing and may well enjoy music (and even if they have no hearing, may find musical enjoyment in feeling the vibrations), and the more profound realisation that for some deaf people the English spoken and written around them may be ‘foreign’ compared to sign language.

Assumptions

All too often, we make assumptions about how other people see things. In this case, the conflict between my assumptions and the evidence led me to investigate, and find out that my assumptions were wrong, but much of the time our assumptions go unchallenged, and so un-investigated. In change projects, this is a particular danger. People who are feeling threatened or alienated by a change may be unwilling to point out that wrong assumptions are being made, even if they are not assuming that “management must have thought of that – it’s not for me to say”. Change managers must try to unearth conflicts like this by building relationships widely, and giving people at all levels encouragement to bring their concerns into the open. Change projects often fail, at least to some degree. I wonder how often that is because the manager did not realise, or bother to find out why, the assumptions were in conflict with the evidence. [contact-form][contact-field label='Name' type='name' required='1'/][contact-field label='Email' type='email' required='1'/][contact-field label='Website' type='url'/][contact-field label='Comment' type='textarea' required='1'/][/contact-form] A recent client experience came to mind when I read the following blog post:

http://sethgodin.typepad.com/seths_blog/2013/12/broken-english.html.

Seth says “you will be misunderstood”, and broadly speaking I agree with him: we all interpret what we hear in the context of our own experiences, however careful the speaker, and those experiences are all different. But I think is important to remember that there are degrees of misunderstanding; not all misunderstandings are equal.

My client had started a change project which was running into difficulty. As I started to talk to his staff, it became clear that they all had slightly different understandings of the objectives of the project. Not only did that mean that there was confusion about where they were trying to get to as a whole, but it also meant that the various workstreams were unlikely to join up.

You won’t be surprised to hear that there was not much formal documentation for the project. I’m sure my client felt he had explained what he wanted very clearly – and if he had been on the receiving end, I am certain that he would have understood himself perfectly. But his audience was not him, and he had not taken the additional step of asking his audience to play back to him to check their understanding.

One of the most important tasks for any project manager is to make sure that project objectives are defined clearly, and that everyone understands them. A key skill for project managers is therefore to be able to put things into simple, unambiguous language that fits the background and culture of everyone in the team. They must be good translators: there may still be some misunderstandings, but if they can’t reduce them to a very low minimum by adapting their language (and their listening) to their different audiences, they will not be effective. Just look what happened at Babel!

A recent client experience came to mind when I read the following blog post:

http://sethgodin.typepad.com/seths_blog/2013/12/broken-english.html.

Seth says “you will be misunderstood”, and broadly speaking I agree with him: we all interpret what we hear in the context of our own experiences, however careful the speaker, and those experiences are all different. But I think is important to remember that there are degrees of misunderstanding; not all misunderstandings are equal.

My client had started a change project which was running into difficulty. As I started to talk to his staff, it became clear that they all had slightly different understandings of the objectives of the project. Not only did that mean that there was confusion about where they were trying to get to as a whole, but it also meant that the various workstreams were unlikely to join up.

You won’t be surprised to hear that there was not much formal documentation for the project. I’m sure my client felt he had explained what he wanted very clearly – and if he had been on the receiving end, I am certain that he would have understood himself perfectly. But his audience was not him, and he had not taken the additional step of asking his audience to play back to him to check their understanding.

One of the most important tasks for any project manager is to make sure that project objectives are defined clearly, and that everyone understands them. A key skill for project managers is therefore to be able to put things into simple, unambiguous language that fits the background and culture of everyone in the team. They must be good translators: there may still be some misunderstandings, but if they can’t reduce them to a very low minimum by adapting their language (and their listening) to their different audiences, they will not be effective. Just look what happened at Babel!

[caption id="" align="alignright" width="240"] Central London Traffic (Photo credit: oatsy40)[/caption]

Driving through London a day or two ago, I was amazed to see in front of me an advertising van unlike any I had ever seen before. Half of the back of the van was taken up with a large screen, repeatedly showing a short advertising video clip, obviously in full view of the drivers behind. It certainly got my attention!

Call me old-fashioned, but this seemed to me to be an innovation too far. Driving in London is hard enough, with heavy traffic, bicycles, pedestrians, buses stopping and starting, complex road layouts etc. to pay attention to, without adding advertising which is so clearly going to distract drivers. Health and Safety rules have a bad reputation, but this seemed to me to be something they really should apply to.

But it did remind me that if you want something to grab someone’s attention, you should make it move! Years ago (even before the first PCs), I was a University Lecturer, and had to put on a display of some research for an open day. Nearly all the displays people made were static. Even though my subject was hard to make exciting for the public, and though my animated display on an early computer screen was small and very crude (in those days anything more would have been very hard), the fact that it moved and had a very simple coordinated sound track attracted far more visitors than most other displays.

Central London Traffic (Photo credit: oatsy40)[/caption]

Driving through London a day or two ago, I was amazed to see in front of me an advertising van unlike any I had ever seen before. Half of the back of the van was taken up with a large screen, repeatedly showing a short advertising video clip, obviously in full view of the drivers behind. It certainly got my attention!

Call me old-fashioned, but this seemed to me to be an innovation too far. Driving in London is hard enough, with heavy traffic, bicycles, pedestrians, buses stopping and starting, complex road layouts etc. to pay attention to, without adding advertising which is so clearly going to distract drivers. Health and Safety rules have a bad reputation, but this seemed to me to be something they really should apply to.

But it did remind me that if you want something to grab someone’s attention, you should make it move! Years ago (even before the first PCs), I was a University Lecturer, and had to put on a display of some research for an open day. Nearly all the displays people made were static. Even though my subject was hard to make exciting for the public, and though my animated display on an early computer screen was small and very crude (in those days anything more would have been very hard), the fact that it moved and had a very simple coordinated sound track attracted far more visitors than most other displays.

Central London Traffic (Photo credit: oatsy40)[/caption]

Driving through London a day or two ago, I was amazed to see in front of me an advertising van unlike any I had ever seen before. Half of the back of the van was taken up with a large screen, repeatedly showing a short advertising video clip, obviously in full view of the drivers behind. It certainly got my attention!

Call me old-fashioned, but this seemed to me to be an innovation too far. Driving in London is hard enough, with heavy traffic, bicycles, pedestrians, buses stopping and starting, complex road layouts etc. to pay attention to, without adding advertising which is so clearly going to distract drivers. Health and Safety rules have a bad reputation, but this seemed to me to be something they really should apply to.

But it did remind me that if you want something to grab someone’s attention, you should make it move! Years ago (even before the first PCs), I was a University Lecturer, and had to put on a display of some research for an open day. Nearly all the displays people made were static. Even though my subject was hard to make exciting for the public, and though my animated display on an early computer screen was small and very crude (in those days anything more would have been very hard), the fact that it moved and had a very simple coordinated sound track attracted far more visitors than most other displays.

Central London Traffic (Photo credit: oatsy40)[/caption]

Driving through London a day or two ago, I was amazed to see in front of me an advertising van unlike any I had ever seen before. Half of the back of the van was taken up with a large screen, repeatedly showing a short advertising video clip, obviously in full view of the drivers behind. It certainly got my attention!

Call me old-fashioned, but this seemed to me to be an innovation too far. Driving in London is hard enough, with heavy traffic, bicycles, pedestrians, buses stopping and starting, complex road layouts etc. to pay attention to, without adding advertising which is so clearly going to distract drivers. Health and Safety rules have a bad reputation, but this seemed to me to be something they really should apply to.

But it did remind me that if you want something to grab someone’s attention, you should make it move! Years ago (even before the first PCs), I was a University Lecturer, and had to put on a display of some research for an open day. Nearly all the displays people made were static. Even though my subject was hard to make exciting for the public, and though my animated display on an early computer screen was small and very crude (in those days anything more would have been very hard), the fact that it moved and had a very simple coordinated sound track attracted far more visitors than most other displays.

Change gets peoples' attention!

Change is like that too. It moves, so it gets peoples' attention, unfortunately more often negatively than positively – like the advertising van did for me. But if you can find a way to make people curious, and if possible engage them in the exploration of the change, the results can be quite different! What is leadership about? The very word implies movement. Leadership involves helping other people to find the way from A to B, so all leadership is change leadership of some kind. If we are sticking to A, the people may need managing, but there is not much leading involved. You don’t need a leader if you are not going anywhere.

How many times have you heard people say “if its not broken, why fix it?” Probably you have said it yourself at times. Or “I don’t want to upset the apple cart”? No-one likes change – everyone is more comfortable with the status quo. The trouble is, stability is an illusion, at least in the longer term. Everything grows - or it declines. The organisation that does not change positively is doomed eventually to change negatively.

Change is the whole point of leadership. The joke says “How many psychologists does it take to change a light bulb? One, but it has to want to change!” The job of the leader is to have the vision of where to go to, and then to get people to the point where they want to, or at least accept the need for, change.

What is leadership about? The very word implies movement. Leadership involves helping other people to find the way from A to B, so all leadership is change leadership of some kind. If we are sticking to A, the people may need managing, but there is not much leading involved. You don’t need a leader if you are not going anywhere.

How many times have you heard people say “if its not broken, why fix it?” Probably you have said it yourself at times. Or “I don’t want to upset the apple cart”? No-one likes change – everyone is more comfortable with the status quo. The trouble is, stability is an illusion, at least in the longer term. Everything grows - or it declines. The organisation that does not change positively is doomed eventually to change negatively.

Change is the whole point of leadership. The joke says “How many psychologists does it take to change a light bulb? One, but it has to want to change!” The job of the leader is to have the vision of where to go to, and then to get people to the point where they want to, or at least accept the need for, change.

[caption id="" align="alignright" width="300"] Tyrannosaurus rex, Palais de la Découverte, Paris (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

Evolution is the natural process by which all forms of life adapt to changes in their environment. It is a very slow process, in which many small changes gradually accumulate. It is unplanned and undirected: who knows how the environment may change in the future, and so what adaptations would put us ahead of the game? Successful changes are not necessarily the best possible choices, merely the best of those that were tested. Different individuals start from different places, and so the adaptations which seem to work will vary. Consequently, over time, divergence will occur until different species result, even though each species can be traced back to a common ancestor. But evolution is brutal too: not all species will make it. Some find they have gone down an evolutionary dead end, and some that change is simply too fast for them to adapt to.

Sometimes organisational change can be like this. I once worked for a public-sector organisation which was privatised, so that it had to change from being ‘mission-led’ to being profit-led. Management set out a vision for what it wanted the organisation to become – essentially a similar, unitary, organisation but in the private sector – but was unable to make the radical changes necessary to deliver it fast enough. Evolution carried on regardless as the primary need to survive forced short-term decisions which deviated from the vision. Without a unifying mission as a common guide, different parts of the organisation evolved in different ways to adapt to their own local environments. Fragmentation followed, with a variety of different destinies for the parts, and a few divisions falling by the wayside. Despite starting down their preferred route of unitary privatisation, the eventual destination was exactly what the original managers had been determined to avoid.

What is the lesson? Ideally of course it should be possible to set out a strategic objective, and then to deliver the changes needed to get there. But if the change required is too great, or the barriers mean change is brought about too slowly, the short-term decisions of evolution may shape the future without regard to management intentions. That does not necessarily make the outcome worse in the greater scheme of things: after all, evolution is about survival of the fittest. But natural selection is an overwhelming force, and if short-term decisions are threatening to de-rail management’s strategic plan, it may be wise to take another look at the plan, and to try to work with evolution rather than against it.

Tyrannosaurus rex, Palais de la Découverte, Paris (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

Evolution is the natural process by which all forms of life adapt to changes in their environment. It is a very slow process, in which many small changes gradually accumulate. It is unplanned and undirected: who knows how the environment may change in the future, and so what adaptations would put us ahead of the game? Successful changes are not necessarily the best possible choices, merely the best of those that were tested. Different individuals start from different places, and so the adaptations which seem to work will vary. Consequently, over time, divergence will occur until different species result, even though each species can be traced back to a common ancestor. But evolution is brutal too: not all species will make it. Some find they have gone down an evolutionary dead end, and some that change is simply too fast for them to adapt to.

Sometimes organisational change can be like this. I once worked for a public-sector organisation which was privatised, so that it had to change from being ‘mission-led’ to being profit-led. Management set out a vision for what it wanted the organisation to become – essentially a similar, unitary, organisation but in the private sector – but was unable to make the radical changes necessary to deliver it fast enough. Evolution carried on regardless as the primary need to survive forced short-term decisions which deviated from the vision. Without a unifying mission as a common guide, different parts of the organisation evolved in different ways to adapt to their own local environments. Fragmentation followed, with a variety of different destinies for the parts, and a few divisions falling by the wayside. Despite starting down their preferred route of unitary privatisation, the eventual destination was exactly what the original managers had been determined to avoid.

What is the lesson? Ideally of course it should be possible to set out a strategic objective, and then to deliver the changes needed to get there. But if the change required is too great, or the barriers mean change is brought about too slowly, the short-term decisions of evolution may shape the future without regard to management intentions. That does not necessarily make the outcome worse in the greater scheme of things: after all, evolution is about survival of the fittest. But natural selection is an overwhelming force, and if short-term decisions are threatening to de-rail management’s strategic plan, it may be wise to take another look at the plan, and to try to work with evolution rather than against it.

Tyrannosaurus rex, Palais de la Découverte, Paris (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

Evolution is the natural process by which all forms of life adapt to changes in their environment. It is a very slow process, in which many small changes gradually accumulate. It is unplanned and undirected: who knows how the environment may change in the future, and so what adaptations would put us ahead of the game? Successful changes are not necessarily the best possible choices, merely the best of those that were tested. Different individuals start from different places, and so the adaptations which seem to work will vary. Consequently, over time, divergence will occur until different species result, even though each species can be traced back to a common ancestor. But evolution is brutal too: not all species will make it. Some find they have gone down an evolutionary dead end, and some that change is simply too fast for them to adapt to.

Sometimes organisational change can be like this. I once worked for a public-sector organisation which was privatised, so that it had to change from being ‘mission-led’ to being profit-led. Management set out a vision for what it wanted the organisation to become – essentially a similar, unitary, organisation but in the private sector – but was unable to make the radical changes necessary to deliver it fast enough. Evolution carried on regardless as the primary need to survive forced short-term decisions which deviated from the vision. Without a unifying mission as a common guide, different parts of the organisation evolved in different ways to adapt to their own local environments. Fragmentation followed, with a variety of different destinies for the parts, and a few divisions falling by the wayside. Despite starting down their preferred route of unitary privatisation, the eventual destination was exactly what the original managers had been determined to avoid.

What is the lesson? Ideally of course it should be possible to set out a strategic objective, and then to deliver the changes needed to get there. But if the change required is too great, or the barriers mean change is brought about too slowly, the short-term decisions of evolution may shape the future without regard to management intentions. That does not necessarily make the outcome worse in the greater scheme of things: after all, evolution is about survival of the fittest. But natural selection is an overwhelming force, and if short-term decisions are threatening to de-rail management’s strategic plan, it may be wise to take another look at the plan, and to try to work with evolution rather than against it.

Tyrannosaurus rex, Palais de la Découverte, Paris (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

Evolution is the natural process by which all forms of life adapt to changes in their environment. It is a very slow process, in which many small changes gradually accumulate. It is unplanned and undirected: who knows how the environment may change in the future, and so what adaptations would put us ahead of the game? Successful changes are not necessarily the best possible choices, merely the best of those that were tested. Different individuals start from different places, and so the adaptations which seem to work will vary. Consequently, over time, divergence will occur until different species result, even though each species can be traced back to a common ancestor. But evolution is brutal too: not all species will make it. Some find they have gone down an evolutionary dead end, and some that change is simply too fast for them to adapt to.

Sometimes organisational change can be like this. I once worked for a public-sector organisation which was privatised, so that it had to change from being ‘mission-led’ to being profit-led. Management set out a vision for what it wanted the organisation to become – essentially a similar, unitary, organisation but in the private sector – but was unable to make the radical changes necessary to deliver it fast enough. Evolution carried on regardless as the primary need to survive forced short-term decisions which deviated from the vision. Without a unifying mission as a common guide, different parts of the organisation evolved in different ways to adapt to their own local environments. Fragmentation followed, with a variety of different destinies for the parts, and a few divisions falling by the wayside. Despite starting down their preferred route of unitary privatisation, the eventual destination was exactly what the original managers had been determined to avoid.

What is the lesson? Ideally of course it should be possible to set out a strategic objective, and then to deliver the changes needed to get there. But if the change required is too great, or the barriers mean change is brought about too slowly, the short-term decisions of evolution may shape the future without regard to management intentions. That does not necessarily make the outcome worse in the greater scheme of things: after all, evolution is about survival of the fittest. But natural selection is an overwhelming force, and if short-term decisions are threatening to de-rail management’s strategic plan, it may be wise to take another look at the plan, and to try to work with evolution rather than against it.  A few years ago I needed to hire an assistant. I’d fixed an interview, and everything was organised. It was five minutes before the time the candidate was due, and I was just collecting my papers and my thoughts. At that moment, the din of the fire alarm started up.

There is – of course – nothing that you can do. Down the concrete back stairs, and out round the back of the building to the assembly point, into the London drizzle without a coat, while I imagined my interviewee arriving at the front. I had left all my papers on my desk in the dry, and had no other record of his contact details, so I had no way to suggest an alternative plan.

A little while later, my mobile rang. Having arrived and been barred from entry, he had managed to track down my mobile number himself, and we were able to arrange to carry on with the interview while we dried out in a local coffee shop. Needless to say, his resourcefulness impressed me and he got the job. Despite the unhelpful circumstances of the interview, he was one of my best hires ever.

Life has a habit of not going the way we plan it. Unexpected circumstances can often be turned to our advantage though, if we grasp them rather than trying to stick to the plan, and often the results are better than you could possibly have expected.

A few years ago I needed to hire an assistant. I’d fixed an interview, and everything was organised. It was five minutes before the time the candidate was due, and I was just collecting my papers and my thoughts. At that moment, the din of the fire alarm started up.

There is – of course – nothing that you can do. Down the concrete back stairs, and out round the back of the building to the assembly point, into the London drizzle without a coat, while I imagined my interviewee arriving at the front. I had left all my papers on my desk in the dry, and had no other record of his contact details, so I had no way to suggest an alternative plan.

A little while later, my mobile rang. Having arrived and been barred from entry, he had managed to track down my mobile number himself, and we were able to arrange to carry on with the interview while we dried out in a local coffee shop. Needless to say, his resourcefulness impressed me and he got the job. Despite the unhelpful circumstances of the interview, he was one of my best hires ever.

Life has a habit of not going the way we plan it. Unexpected circumstances can often be turned to our advantage though, if we grasp them rather than trying to stick to the plan, and often the results are better than you could possibly have expected.  Have you ever noticed how the crowds waiting for commuter trains at Paddington (or doubtless most other big terminus stations) nearly all stay on the concourse until the platform is announced, even though each train usually runs from the same platform every day (so the regular commuters who are the majority all know which it is likely to be)? Consequence – a great crush as everyone rushes at the ticket barriers at once.

Have you ever noticed how the crowds waiting for commuter trains at Paddington (or doubtless most other big terminus stations) nearly all stay on the concourse until the platform is announced, even though each train usually runs from the same platform every day (so the regular commuters who are the majority all know which it is likely to be)? Consequence – a great crush as everyone rushes at the ticket barriers at once.

Beating the crowd

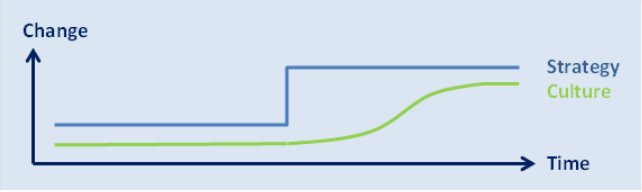

There are always a small number of people who don’t wait. They go calmly through the barrier with no queues, and get seats exactly where they want, beating the crowd instead of risking no seat at all. Maybe once in a blue moon the platform is different and they have to move – but it’s rare. It’s a great illustration of how conformist people (or at least we Brits) tend to be. I would guess less than 5% make the rational risk-reward trade-off and act accordingly, beating the crowd. 95% of us prefer to be part of the herd – but I wonder whether it is the people you would expect? Now there’s an interesting way to separate the sheep from the goats! Given those proportions, it is hardly surprising that very few people embrace change before they have to – even if they would stand to benefit from being early adopters. On the other hand, as change managers we have no need to wait until everything is ready before making announcements, unlike station staff. Early communication leads to more organised loading! Organisations need two essential frameworks to be able to deliver effectively, both of which must be consistent with the organisation’s vision and mission: strategy and culture. Strategy, describing WHAT they will deliver, and Culture, defining HOW they will deliver it. Usually lots of effort is put into defining the strategy, but culture often just ‘happens’. Nonetheless, success depends on the two working harmoniously together. Take a look at this article for another view of this.

What happens when an organisation faces a disruptive change to its environment? This might be something like an economic or technological change, or, for a major project, might just be moving from promotion to delivery. The first step is usually to update the strategy (and possibly the vision and mission as well) to respond to the change.

So what’s the problem? I think it is that frequently there is no recognition that the change may also require changes to culture to keep it aligned with the strategy. But even if such a change is planned and managed, culture stems from the way people think and behave, and changing it relies on people changing: it cannot be made to change quickly, and certainly not at the same speed as the strategy changes. The disruptive change to strategy then leads to a misalignment between strategy and culture, and this takes time to heal.

Here are two examples where strategy and culture both mattered:

Privatisation

I once worked at a public sector organisation that was privatised. There was a massive (even though long-anticipated) disruptive change in the environment when the transfer happened. Overnight, share price and city reaction to performance became critical, and even though strategy had been becoming more commercial for some while, suddenly it really mattered. Some staff were simply unable to make the cultural shift required for alignment – meaning that until most of those had left or retired, the culture did not become fully commercial. Unfortunately, this process took years – years we did not have.

Major project transition

I also once worked for an organisation set up to plan and build a major infrastructure project. Having for years been focussed on planning and promoting the project, following approval, it suddenly had the challenge of delivering a huge construction project. What had been a fairly small public sector organisation with centralised decision making needed to become an effective delivery organisation in short order. To gain the necessary scale and capability, it let large contracts to firms which were highly experienced in delivering large infrastructure projects. While they brought the energy and focus essential for delivery, it took much longer to bring about an organisational culture that was aligned across staff from all three organisations.

Transition is hard because it requires managing these very different strands in a joined-up way. It needs, on the one hand, the development and implementation of new strategies, requiring vision, analysis, and delivery skills; on the other, bringing about a realignment of culture with minimum delay, requiring people, communication and change skills. And to join them up, it also needs a tolerance for the ambiguity that results while strategy and culture remain out of alignment.

If you are facing a disruptive change, and would like to talk about how to manage the consequences in a joined-up way, contact david@otteryconsulting.co.uk.

Organisations need two essential frameworks to be able to deliver effectively, both of which must be consistent with the organisation’s vision and mission: strategy and culture. Strategy, describing WHAT they will deliver, and Culture, defining HOW they will deliver it. Usually lots of effort is put into defining the strategy, but culture often just ‘happens’. Nonetheless, success depends on the two working harmoniously together. Take a look at this article for another view of this.

What happens when an organisation faces a disruptive change to its environment? This might be something like an economic or technological change, or, for a major project, might just be moving from promotion to delivery. The first step is usually to update the strategy (and possibly the vision and mission as well) to respond to the change.

So what’s the problem? I think it is that frequently there is no recognition that the change may also require changes to culture to keep it aligned with the strategy. But even if such a change is planned and managed, culture stems from the way people think and behave, and changing it relies on people changing: it cannot be made to change quickly, and certainly not at the same speed as the strategy changes. The disruptive change to strategy then leads to a misalignment between strategy and culture, and this takes time to heal.

Here are two examples where strategy and culture both mattered:

Privatisation

I once worked at a public sector organisation that was privatised. There was a massive (even though long-anticipated) disruptive change in the environment when the transfer happened. Overnight, share price and city reaction to performance became critical, and even though strategy had been becoming more commercial for some while, suddenly it really mattered. Some staff were simply unable to make the cultural shift required for alignment – meaning that until most of those had left or retired, the culture did not become fully commercial. Unfortunately, this process took years – years we did not have.

Major project transition

I also once worked for an organisation set up to plan and build a major infrastructure project. Having for years been focussed on planning and promoting the project, following approval, it suddenly had the challenge of delivering a huge construction project. What had been a fairly small public sector organisation with centralised decision making needed to become an effective delivery organisation in short order. To gain the necessary scale and capability, it let large contracts to firms which were highly experienced in delivering large infrastructure projects. While they brought the energy and focus essential for delivery, it took much longer to bring about an organisational culture that was aligned across staff from all three organisations.

Transition is hard because it requires managing these very different strands in a joined-up way. It needs, on the one hand, the development and implementation of new strategies, requiring vision, analysis, and delivery skills; on the other, bringing about a realignment of culture with minimum delay, requiring people, communication and change skills. And to join them up, it also needs a tolerance for the ambiguity that results while strategy and culture remain out of alignment.

If you are facing a disruptive change, and would like to talk about how to manage the consequences in a joined-up way, contact david@otteryconsulting.co.uk.