What is leadership about? The very word implies movement. Leadership involves helping other people to find the way from A to B, so all leadership is change leadership of some kind. If we are sticking to A, the people may need managing, but there is not much leading involved. You don’t need a leader if you are not going anywhere.

How many times have you heard people say “if its not broken, why fix it?” Probably you have said it yourself at times. Or “I don’t want to upset the apple cart”? No-one likes change – everyone is more comfortable with the status quo. The trouble is, stability is an illusion, at least in the longer term. Everything grows - or it declines. The organisation that does not change positively is doomed eventually to change negatively.

Change is the whole point of leadership. The joke says “How many psychologists does it take to change a light bulb? One, but it has to want to change!” The job of the leader is to have the vision of where to go to, and then to get people to the point where they want to, or at least accept the need for, change.

What is leadership about? The very word implies movement. Leadership involves helping other people to find the way from A to B, so all leadership is change leadership of some kind. If we are sticking to A, the people may need managing, but there is not much leading involved. You don’t need a leader if you are not going anywhere.

How many times have you heard people say “if its not broken, why fix it?” Probably you have said it yourself at times. Or “I don’t want to upset the apple cart”? No-one likes change – everyone is more comfortable with the status quo. The trouble is, stability is an illusion, at least in the longer term. Everything grows - or it declines. The organisation that does not change positively is doomed eventually to change negatively.

Change is the whole point of leadership. The joke says “How many psychologists does it take to change a light bulb? One, but it has to want to change!” The job of the leader is to have the vision of where to go to, and then to get people to the point where they want to, or at least accept the need for, change.

Review of 11 Rules for Creating Value in the Social Era by Nilofer Merchant

Perhaps surprisingly, given the title, Nilofer Merchant’s short book is not so much about the ‘how’ of social media, as the paradigm shift it has enabled in the way that most of the world does business.

In the old days, ‘efficiency’ – doing things right – ruled. You made more money by having more efficient processes, and by having the scale to cover your high fixed costs easily. Large dominant players with efficient processes made it almost impossible for small companies to overcome the barriers to entry. In the past those approaches may also have been ‘effective’ – doing the right things – but the context has changed.

In the new world, while scale and efficiency can be good strategies where there are low levels of innovation and change, the inherently cautious response of big, efficient organisations becomes a disadvantage: the ‘right things’ change too fast. High rates of innovation and change have become possible through the power of social media. Merchant says that a new approach is needed, based on embracing what social media enables, characterised by

Perhaps surprisingly, given the title, Nilofer Merchant’s short book is not so much about the ‘how’ of social media, as the paradigm shift it has enabled in the way that most of the world does business.

In the old days, ‘efficiency’ – doing things right – ruled. You made more money by having more efficient processes, and by having the scale to cover your high fixed costs easily. Large dominant players with efficient processes made it almost impossible for small companies to overcome the barriers to entry. In the past those approaches may also have been ‘effective’ – doing the right things – but the context has changed.

In the new world, while scale and efficiency can be good strategies where there are low levels of innovation and change, the inherently cautious response of big, efficient organisations becomes a disadvantage: the ‘right things’ change too fast. High rates of innovation and change have become possible through the power of social media. Merchant says that a new approach is needed, based on embracing what social media enables, characterised by

- Community: A far more flexible way of allocating work;

- Creativity: Allowing co-creation of value with customers;

- Connections: A more open approach than in the past to customer relationships.

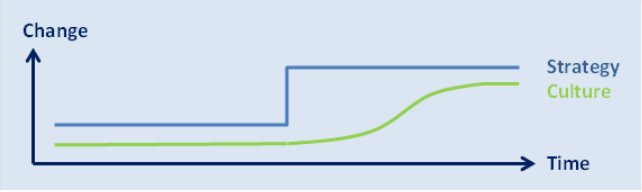

Organisations need two essential frameworks to be able to deliver effectively, both of which must be consistent with the organisation’s vision and mission: strategy and culture. Strategy, describing WHAT they will deliver, and Culture, defining HOW they will deliver it. Usually lots of effort is put into defining the strategy, but culture often just ‘happens’. Nonetheless, success depends on the two working harmoniously together. Take a look at this article for another view of this.

What happens when an organisation faces a disruptive change to its environment? This might be something like an economic or technological change, or, for a major project, might just be moving from promotion to delivery. The first step is usually to update the strategy (and possibly the vision and mission as well) to respond to the change.

So what’s the problem? I think it is that frequently there is no recognition that the change may also require changes to culture to keep it aligned with the strategy. But even if such a change is planned and managed, culture stems from the way people think and behave, and changing it relies on people changing: it cannot be made to change quickly, and certainly not at the same speed as the strategy changes. The disruptive change to strategy then leads to a misalignment between strategy and culture, and this takes time to heal.

Here are two examples where strategy and culture both mattered:

Privatisation

I once worked at a public sector organisation that was privatised. There was a massive (even though long-anticipated) disruptive change in the environment when the transfer happened. Overnight, share price and city reaction to performance became critical, and even though strategy had been becoming more commercial for some while, suddenly it really mattered. Some staff were simply unable to make the cultural shift required for alignment – meaning that until most of those had left or retired, the culture did not become fully commercial. Unfortunately, this process took years – years we did not have.

Major project transition

I also once worked for an organisation set up to plan and build a major infrastructure project. Having for years been focussed on planning and promoting the project, following approval, it suddenly had the challenge of delivering a huge construction project. What had been a fairly small public sector organisation with centralised decision making needed to become an effective delivery organisation in short order. To gain the necessary scale and capability, it let large contracts to firms which were highly experienced in delivering large infrastructure projects. While they brought the energy and focus essential for delivery, it took much longer to bring about an organisational culture that was aligned across staff from all three organisations.

Transition is hard because it requires managing these very different strands in a joined-up way. It needs, on the one hand, the development and implementation of new strategies, requiring vision, analysis, and delivery skills; on the other, bringing about a realignment of culture with minimum delay, requiring people, communication and change skills. And to join them up, it also needs a tolerance for the ambiguity that results while strategy and culture remain out of alignment.

If you are facing a disruptive change, and would like to talk about how to manage the consequences in a joined-up way, contact david@otteryconsulting.co.uk.

Organisations need two essential frameworks to be able to deliver effectively, both of which must be consistent with the organisation’s vision and mission: strategy and culture. Strategy, describing WHAT they will deliver, and Culture, defining HOW they will deliver it. Usually lots of effort is put into defining the strategy, but culture often just ‘happens’. Nonetheless, success depends on the two working harmoniously together. Take a look at this article for another view of this.

What happens when an organisation faces a disruptive change to its environment? This might be something like an economic or technological change, or, for a major project, might just be moving from promotion to delivery. The first step is usually to update the strategy (and possibly the vision and mission as well) to respond to the change.

So what’s the problem? I think it is that frequently there is no recognition that the change may also require changes to culture to keep it aligned with the strategy. But even if such a change is planned and managed, culture stems from the way people think and behave, and changing it relies on people changing: it cannot be made to change quickly, and certainly not at the same speed as the strategy changes. The disruptive change to strategy then leads to a misalignment between strategy and culture, and this takes time to heal.

Here are two examples where strategy and culture both mattered:

Privatisation

I once worked at a public sector organisation that was privatised. There was a massive (even though long-anticipated) disruptive change in the environment when the transfer happened. Overnight, share price and city reaction to performance became critical, and even though strategy had been becoming more commercial for some while, suddenly it really mattered. Some staff were simply unable to make the cultural shift required for alignment – meaning that until most of those had left or retired, the culture did not become fully commercial. Unfortunately, this process took years – years we did not have.

Major project transition

I also once worked for an organisation set up to plan and build a major infrastructure project. Having for years been focussed on planning and promoting the project, following approval, it suddenly had the challenge of delivering a huge construction project. What had been a fairly small public sector organisation with centralised decision making needed to become an effective delivery organisation in short order. To gain the necessary scale and capability, it let large contracts to firms which were highly experienced in delivering large infrastructure projects. While they brought the energy and focus essential for delivery, it took much longer to bring about an organisational culture that was aligned across staff from all three organisations.

Transition is hard because it requires managing these very different strands in a joined-up way. It needs, on the one hand, the development and implementation of new strategies, requiring vision, analysis, and delivery skills; on the other, bringing about a realignment of culture with minimum delay, requiring people, communication and change skills. And to join them up, it also needs a tolerance for the ambiguity that results while strategy and culture remain out of alignment.

If you are facing a disruptive change, and would like to talk about how to manage the consequences in a joined-up way, contact david@otteryconsulting.co.uk.

What happens when an organisation grows up? Many things, but it is not so different from a child growing up: it develops organisation maturity.

As a child grows up, it develops its own habits, values, behaviours. It makes friends. It learns how to do things it could not do before. And it learns how to blend and adapt all of those things to create a consistent whole – its personality. With that comes self-confidence.

So it is with an organisation. In a young organisation – even a large one, perhaps formed from a merger – processes and structures may have been patched together un-adapted from different inheritances. Initially, the mixture of values, relationships, and so on, is unlikely to be self-consistent. Although they may be individually very experienced, managers are not used to working together, and do not know how each other will react in different circumstances. Trust takes time to develop.

Even for an established organisation, a major disruptive change in its environment can cause the same difficulties. The new environment is unfamiliar and the managers of the organisation may have varying responses. Confidence and trust in each other’s judgement in the new situation need to be re-established. Perhaps new people join the team. Processes and systems may need to be changed, because the organisation and its strategy are no longer aligned.

Nobody expects a small, young organisation to behave like a major corporation. However, with scale comes expectation. If you look like a grown-up, people expect you to behave like a grown-up and to have grown-up relationships. Just as with a child who looks much older than it is, the incongruity can cause difficulty for everyone.

Organisational self-confidence – maturity if you will – matters. When an organisation knows at all levels that ‘this is the way we do things round here’, everyone in it can stand their ground with confidence if they need to, in the knowledge that all their colleagues would back them up. Where there is underlying inconsistency, people do not have that confidence. Then it can feel as if you are standing on your own, rather than backed by a team - the whole is not greater than the sum of the parts. So an organisation in this situation needs to grow up fast.

What does it take to do something about this?

First, recognise the nature of the problem. Fundamentally the challenge is about joining things up. That makes it multi-dimensional, multi-functional, crossing all the silos. That in itself means the response has to be driven or at least supported from the top. It also means that it is best done by someone with no vested interest in the outcome. And while it will require detailed analytical work to understand and correct specific problems, it will also need influencing and people skills to ensure that the solutions are accepted and embraced.

I have worked in a number of organisations which have faced challenges of this sort, and helped them to find their way through them. If you are facing similar challenges which you would like to discuss, please contact me at david@otteryconsulting.co.uk.

Have you ever been in a situation where it is obvious from the way management is behaving that something is going on, but where no-one will explain? If so, how did you react?

Suppose you were selling a division of a business, what would you tell the division staff about what is happening, and when?

Management’s instinct always seems to be to say nothing until staff can be told everything – which might not be until the deal has already been signed. It is hard to argue against the objection that the deal is market-sensitive information, and that telling them anything would risk breaking Stock Exchange rules. But does that argument really hold water?

In asset sale projects I have run, it has always been essential to include in the project team – and therefore to inform - some people from the division concerned:

• They have to supply much of the due diligence information;

• The bidders want to meet the managers;

• And they want to walk round the assets they are buying.

Of course many people not directly involved notice the unusual visitors, the unusual questions, the unusual gathering of documents. They probably hear of a ‘Project X’. They are not stupid. They realise that something is going on.

Have you ever been in a situation where it is obvious from the way management is behaving that something is going on, but where no-one will explain? If so, how did you react?

Suppose you were selling a division of a business, what would you tell the division staff about what is happening, and when?

Management’s instinct always seems to be to say nothing until staff can be told everything – which might not be until the deal has already been signed. It is hard to argue against the objection that the deal is market-sensitive information, and that telling them anything would risk breaking Stock Exchange rules. But does that argument really hold water?

In asset sale projects I have run, it has always been essential to include in the project team – and therefore to inform - some people from the division concerned:

• They have to supply much of the due diligence information;

• The bidders want to meet the managers;

• And they want to walk round the assets they are buying.

Of course many people not directly involved notice the unusual visitors, the unusual questions, the unusual gathering of documents. They probably hear of a ‘Project X’. They are not stupid. They realise that something is going on.