“Many are stubborn in pursuit of the path they have chosen. Few in pursuit of the goal.”

Friedrich Nietzsche

Why does that matter? Because as circumstances change, the path has to change. Your objective, your destination, remains the same, but the path you need to take to get there has to take account of unforeseen obstacles, newly-visible short cuts, etc. Obstinately pursuing the original path may lead you into unnecessary difficulties or delays, or even to somewhere different altogether. Of course that assumes that you knew where you were going in the first place. In my experience, often people are unwilling or even unable to define their goals really clearly. If you don't do that, all you have left to cling to is the path you have chosen - even when it is leading you to the wrong place!

I’ve been told that, faced with an impending pile-up on the road in front of you, you are most likely to avoid it if you keep your eyes on the space you need to drive into, not on the car you are about to hit – but to do so is very hard! Similarly, being flexible enough to adapt the path you take through change, while keeping your eyes on the ultimate goal, is most likely to deliver what you wanted. Most of my work is concerned with 'soft' projects where the ability to flex when circumstances change is key. Nietsche captured the problem beautifully.

“Many are stubborn in pursuit of the path they have chosen. Few in pursuit of the goal.”

Friedrich Nietzsche

Why does that matter? Because as circumstances change, the path has to change. Your objective, your destination, remains the same, but the path you need to take to get there has to take account of unforeseen obstacles, newly-visible short cuts, etc. Obstinately pursuing the original path may lead you into unnecessary difficulties or delays, or even to somewhere different altogether. Of course that assumes that you knew where you were going in the first place. In my experience, often people are unwilling or even unable to define their goals really clearly. If you don't do that, all you have left to cling to is the path you have chosen - even when it is leading you to the wrong place!

I’ve been told that, faced with an impending pile-up on the road in front of you, you are most likely to avoid it if you keep your eyes on the space you need to drive into, not on the car you are about to hit – but to do so is very hard! Similarly, being flexible enough to adapt the path you take through change, while keeping your eyes on the ultimate goal, is most likely to deliver what you wanted. Most of my work is concerned with 'soft' projects where the ability to flex when circumstances change is key. Nietsche captured the problem beautifully.  I’m on my way to a Board meeting. My job as a Board member is to turn up about once a month for a meeting lasting normally no more than a couple of hours to take the most important decisions the company needs – decisions which are often about complex areas, fraught with operational, commercial, legal and possibly political implications, and often with ambitious managers or other vested interests arguing strongly (but not necessarily objectively) for their preferred outcome. Few of the decisions are black and white, but most carry significant risk for the organisation. Good outcomes rely on informing Board members effectively.

This is a well-managed organisation, so I have received the papers for the meeting a week in advance, but I have had no chance to seek clarification of anything which is unclear, or to ask for further information. In many organisations, the papers may arrive late, or they may have been poorly written so that the story they tell is incomplete or hard to understand (despite often being very detailed), or both. The Board meeting, with a packed agenda and a timetable to keep to, is my only chance to fill the gaps.

I have years of experience to draw on, but experience can only take me so far. Will I miss an assumption that ought to be challenged, or a risk arising from something I am not familiar with? If that happens, we may make a poor decision, and I will share the responsibility. In some cases – for instance a safety issue - that might have serious consequences for other people. It’s not a happy thought.

I’m on my way to a Board meeting. My job as a Board member is to turn up about once a month for a meeting lasting normally no more than a couple of hours to take the most important decisions the company needs – decisions which are often about complex areas, fraught with operational, commercial, legal and possibly political implications, and often with ambitious managers or other vested interests arguing strongly (but not necessarily objectively) for their preferred outcome. Few of the decisions are black and white, but most carry significant risk for the organisation. Good outcomes rely on informing Board members effectively.

This is a well-managed organisation, so I have received the papers for the meeting a week in advance, but I have had no chance to seek clarification of anything which is unclear, or to ask for further information. In many organisations, the papers may arrive late, or they may have been poorly written so that the story they tell is incomplete or hard to understand (despite often being very detailed), or both. The Board meeting, with a packed agenda and a timetable to keep to, is my only chance to fill the gaps.

I have years of experience to draw on, but experience can only take me so far. Will I miss an assumption that ought to be challenged, or a risk arising from something I am not familiar with? If that happens, we may make a poor decision, and I will share the responsibility. In some cases – for instance a safety issue - that might have serious consequences for other people. It’s not a happy thought.

Informing Board members

In order for a Board (or any other body) to make good decisions, it has to be in possession of appropriate information. These are some of the rules I have followed when I have set up arrangements to promote effective governance.Good papers

Good papers tell the story completely and logically, but concisely. They do not assume that the reader knows the background. They build the picture without jumping around, and make clear and well-argued recommendations. They do not confuse with unnecessary detail, but nor do they overlook important aspects. As Einstein said, “If you can't explain it simply, you don't understand it well enough." Provide rules on length, apply (pragmatic) quality control to the papers received, and refuse to include papers if they do not meet minimum requirements (obviously it helps to be able to give advice on how to make them acceptable). You must of course choose a reviewer whose judgements will be respected. This may well result in some painful discussions, but people only learn the hard way.Timely distribution

If members do not have time to read the papers properly, it does not matter how good they are. If I am a busy Board member, I may need to reserve time in my diary for meeting preparation, and this is a problem if I cannot rely on papers arriving on time. Set submission deadlines which allow for timely and predictable distribution, and enforce them. Again, be prepared for some painful discussions until people learn.Informal channels

Concise papers and busy Board meetings are never going to allow for deep understanding of context. To overcome this, I have organised informal sessions immediately preceding Board meetings, over a sandwich lunch if the timing requires. Allocate a couple of hours for just two or three topics; bring in the subject experts, but spend most of the time on discussion. Not all Board members will be able to attend every session, but in my experience not only have they found them hugely valuable in building their wider knowledge of the business, but the opportunity to meet more junior staff has been appreciated all round. There are many other ways that informal channels could be set up. Different things will work in different organisations. Key to all of them is building trust: informing Board members properly means allowing them to see things “warts and all”, and trusting a wider group of staff to talk to them.Organisation

To do all of these things effectively, you need to have someone (or in larger organisations a small secretariat team) whose primary objective is to deliver them. This is not glamorous stuff, however important, and it easily gets put to the bottom of the pile without clear leadership. Finally, remember that nothing will happen unless the importance of this is understood at the very top. If the CEO does not set an example by sticking to time and quality rules, no one else will. Have you ever noticed how the crowds waiting for commuter trains at Paddington (or doubtless most other big terminus stations) nearly all stay on the concourse until the platform is announced, even though each train usually runs from the same platform every day (so the regular commuters who are the majority all know which it is likely to be)? Consequence – a great crush as everyone rushes at the ticket barriers at once.

Have you ever noticed how the crowds waiting for commuter trains at Paddington (or doubtless most other big terminus stations) nearly all stay on the concourse until the platform is announced, even though each train usually runs from the same platform every day (so the regular commuters who are the majority all know which it is likely to be)? Consequence – a great crush as everyone rushes at the ticket barriers at once.

Beating the crowd

There are always a small number of people who don’t wait. They go calmly through the barrier with no queues, and get seats exactly where they want, beating the crowd instead of risking no seat at all. Maybe once in a blue moon the platform is different and they have to move – but it’s rare. It’s a great illustration of how conformist people (or at least we Brits) tend to be. I would guess less than 5% make the rational risk-reward trade-off and act accordingly, beating the crowd. 95% of us prefer to be part of the herd – but I wonder whether it is the people you would expect? Now there’s an interesting way to separate the sheep from the goats! Given those proportions, it is hardly surprising that very few people embrace change before they have to – even if they would stand to benefit from being early adopters. On the other hand, as change managers we have no need to wait until everything is ready before making announcements, unlike station staff. Early communication leads to more organised loading! Oxford is a city that is full of tourists, and in the UK where there are tourists, there are brown signs to direct them to the attractions. As well as the name of the attraction, a sign often also has what might best be called (by analogy with IT) an icon. The sign in the picture shows the word ‘Sheldonian' and a mask – the icon for a theatre. As you might guess, it directs you to the Sheldonian Theatre. So far so good.

There is just one problem. The theatre in question is not a place where you go to see plays. It is in fact the main ceremonial building of the university, where amongst other things, students are admitted, and all being well, later receive their degrees. I don’t suppose it confuses proud parents attending the ceremony, but I wonder what less well-informed tourists make of it?

Oxford is a city that is full of tourists, and in the UK where there are tourists, there are brown signs to direct them to the attractions. As well as the name of the attraction, a sign often also has what might best be called (by analogy with IT) an icon. The sign in the picture shows the word ‘Sheldonian' and a mask – the icon for a theatre. As you might guess, it directs you to the Sheldonian Theatre. So far so good.

There is just one problem. The theatre in question is not a place where you go to see plays. It is in fact the main ceremonial building of the university, where amongst other things, students are admitted, and all being well, later receive their degrees. I don’t suppose it confuses proud parents attending the ceremony, but I wonder what less well-informed tourists make of it?

Poor branding

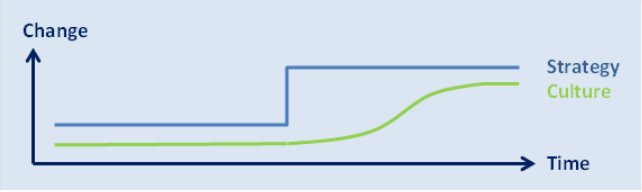

I won’t speculate on whether the person who designed the sign realised what they were doing, but it reminded me of an important business truth. Broadly interpreted, what happened here was poor branding – the icon was inconsistent with the meaning, potentially leading to confusion and frustration. The importance of consistency and integrity of messages is universal, whether or not the messages we are giving would conventionally be thought of as branding. When everything we see and hear is consistent, we believe in the authenticity of the message, and that builds trust, be it in a product, an organisation, a person, or a set of signs. When we realise that that consistency is lacking, trust is lost - even if only in the brown signs. Any time you want to build trust, think of yourself as managing your own brand. As change managers, the ability to build trust is one of our most important skills – so we can't afford poor branding. Whatever and however you are communicating (particularly when you are not deliberately communicating at all!), be authentic – then you will also have that essential consistency. Perhaps it does not matter if one set of signs has an odd choice of image, or just how much the signs are trusted. But how many times have you made similar mistakes, which may have had worse consequences? Organisations need two essential frameworks to be able to deliver effectively, both of which must be consistent with the organisation’s vision and mission: strategy and culture. Strategy, describing WHAT they will deliver, and Culture, defining HOW they will deliver it. Usually lots of effort is put into defining the strategy, but culture often just ‘happens’. Nonetheless, success depends on the two working harmoniously together. Take a look at this article for another view of this.

What happens when an organisation faces a disruptive change to its environment? This might be something like an economic or technological change, or, for a major project, might just be moving from promotion to delivery. The first step is usually to update the strategy (and possibly the vision and mission as well) to respond to the change.

So what’s the problem? I think it is that frequently there is no recognition that the change may also require changes to culture to keep it aligned with the strategy. But even if such a change is planned and managed, culture stems from the way people think and behave, and changing it relies on people changing: it cannot be made to change quickly, and certainly not at the same speed as the strategy changes. The disruptive change to strategy then leads to a misalignment between strategy and culture, and this takes time to heal.

Here are two examples where strategy and culture both mattered:

Privatisation

I once worked at a public sector organisation that was privatised. There was a massive (even though long-anticipated) disruptive change in the environment when the transfer happened. Overnight, share price and city reaction to performance became critical, and even though strategy had been becoming more commercial for some while, suddenly it really mattered. Some staff were simply unable to make the cultural shift required for alignment – meaning that until most of those had left or retired, the culture did not become fully commercial. Unfortunately, this process took years – years we did not have.

Major project transition

I also once worked for an organisation set up to plan and build a major infrastructure project. Having for years been focussed on planning and promoting the project, following approval, it suddenly had the challenge of delivering a huge construction project. What had been a fairly small public sector organisation with centralised decision making needed to become an effective delivery organisation in short order. To gain the necessary scale and capability, it let large contracts to firms which were highly experienced in delivering large infrastructure projects. While they brought the energy and focus essential for delivery, it took much longer to bring about an organisational culture that was aligned across staff from all three organisations.

Transition is hard because it requires managing these very different strands in a joined-up way. It needs, on the one hand, the development and implementation of new strategies, requiring vision, analysis, and delivery skills; on the other, bringing about a realignment of culture with minimum delay, requiring people, communication and change skills. And to join them up, it also needs a tolerance for the ambiguity that results while strategy and culture remain out of alignment.

If you are facing a disruptive change, and would like to talk about how to manage the consequences in a joined-up way, contact david@otteryconsulting.co.uk.

Organisations need two essential frameworks to be able to deliver effectively, both of which must be consistent with the organisation’s vision and mission: strategy and culture. Strategy, describing WHAT they will deliver, and Culture, defining HOW they will deliver it. Usually lots of effort is put into defining the strategy, but culture often just ‘happens’. Nonetheless, success depends on the two working harmoniously together. Take a look at this article for another view of this.

What happens when an organisation faces a disruptive change to its environment? This might be something like an economic or technological change, or, for a major project, might just be moving from promotion to delivery. The first step is usually to update the strategy (and possibly the vision and mission as well) to respond to the change.

So what’s the problem? I think it is that frequently there is no recognition that the change may also require changes to culture to keep it aligned with the strategy. But even if such a change is planned and managed, culture stems from the way people think and behave, and changing it relies on people changing: it cannot be made to change quickly, and certainly not at the same speed as the strategy changes. The disruptive change to strategy then leads to a misalignment between strategy and culture, and this takes time to heal.

Here are two examples where strategy and culture both mattered:

Privatisation

I once worked at a public sector organisation that was privatised. There was a massive (even though long-anticipated) disruptive change in the environment when the transfer happened. Overnight, share price and city reaction to performance became critical, and even though strategy had been becoming more commercial for some while, suddenly it really mattered. Some staff were simply unable to make the cultural shift required for alignment – meaning that until most of those had left or retired, the culture did not become fully commercial. Unfortunately, this process took years – years we did not have.

Major project transition

I also once worked for an organisation set up to plan and build a major infrastructure project. Having for years been focussed on planning and promoting the project, following approval, it suddenly had the challenge of delivering a huge construction project. What had been a fairly small public sector organisation with centralised decision making needed to become an effective delivery organisation in short order. To gain the necessary scale and capability, it let large contracts to firms which were highly experienced in delivering large infrastructure projects. While they brought the energy and focus essential for delivery, it took much longer to bring about an organisational culture that was aligned across staff from all three organisations.

Transition is hard because it requires managing these very different strands in a joined-up way. It needs, on the one hand, the development and implementation of new strategies, requiring vision, analysis, and delivery skills; on the other, bringing about a realignment of culture with minimum delay, requiring people, communication and change skills. And to join them up, it also needs a tolerance for the ambiguity that results while strategy and culture remain out of alignment.

If you are facing a disruptive change, and would like to talk about how to manage the consequences in a joined-up way, contact david@otteryconsulting.co.uk.  Have you ever been in a situation where it is obvious from the way management is behaving that something is going on, but where no-one will explain? If so, how did you react?

Suppose you were selling a division of a business, what would you tell the division staff about what is happening, and when?

Management’s instinct always seems to be to say nothing until staff can be told everything – which might not be until the deal has already been signed. It is hard to argue against the objection that the deal is market-sensitive information, and that telling them anything would risk breaking Stock Exchange rules. But does that argument really hold water?

In asset sale projects I have run, it has always been essential to include in the project team – and therefore to inform - some people from the division concerned:

• They have to supply much of the due diligence information;

• The bidders want to meet the managers;

• And they want to walk round the assets they are buying.

Of course many people not directly involved notice the unusual visitors, the unusual questions, the unusual gathering of documents. They probably hear of a ‘Project X’. They are not stupid. They realise that something is going on.

Have you ever been in a situation where it is obvious from the way management is behaving that something is going on, but where no-one will explain? If so, how did you react?

Suppose you were selling a division of a business, what would you tell the division staff about what is happening, and when?

Management’s instinct always seems to be to say nothing until staff can be told everything – which might not be until the deal has already been signed. It is hard to argue against the objection that the deal is market-sensitive information, and that telling them anything would risk breaking Stock Exchange rules. But does that argument really hold water?

In asset sale projects I have run, it has always been essential to include in the project team – and therefore to inform - some people from the division concerned:

• They have to supply much of the due diligence information;

• The bidders want to meet the managers;

• And they want to walk round the assets they are buying.

Of course many people not directly involved notice the unusual visitors, the unusual questions, the unusual gathering of documents. They probably hear of a ‘Project X’. They are not stupid. They realise that something is going on.

What will you tell them?

So what happens? The rumour mill goes into overdrive. Speculation in the corridors mounts (and is usually much more threatening than the true story would be). Productivity probably falls – the last thing the company wants just now. The potential for (accidentally) unhelpful comments being made to bidders or to media fishing calls grows – and of course you can’t control what you have not told people. Isn’t it better to treat staff as grownups? What will you tell them? Tell them honestly what you can tell them, and they will understand that there are things you can’t. Tell them the confidentiality rules you need them to follow, and why. Listen to their concerns, and tell them more as and when you can. It may seem like the riskier route, but when I have been open, I have always found that people respect the confidence and cooperate willingly. Not only that, but as a result of feeling better about the relationship with you, they often volunteer useful comments or help. Treating people as grownups means trusting them. If you don’t treat them as grownups, why would you be surprised if they don’t behave that way? Your transition is most likely to be smooth if you keep everyone on board during the process. If you would like to talk about how to do that, contact david@otteryconsulting.co.uk. What approaches do you use to encourage the behaviour you want from employees? And do they have the effect you intended? Are you sure?

When I was a very new manager, I remember being impressed by a retired site director of a multinational company, who told me how he had had a pad of gold-coloured paper stars printed, and how every time he heard of an employee who had done a particularly good piece of work, he would hand-write a thank you on a star and send it. People were proud to receive stars – some even had several pinned up where others could see them. They obviously valued the recognition. But he didn’t say anything about the people who didn’t receive gold stars.

What approaches do you use to encourage the behaviour you want from employees? And do they have the effect you intended? Are you sure?

When I was a very new manager, I remember being impressed by a retired site director of a multinational company, who told me how he had had a pad of gold-coloured paper stars printed, and how every time he heard of an employee who had done a particularly good piece of work, he would hand-write a thank you on a star and send it. People were proud to receive stars – some even had several pinned up where others could see them. They obviously valued the recognition. But he didn’t say anything about the people who didn’t receive gold stars.