As an interim manager, I rely on networks to find my next assignment. Many of the people in my immediate network I have known for years, but I still make sure I keep in touch. It only needs the occasional coffee, phone call or email. With newer contacts that I know less well, I make more effort to build the relationship.

Most of those people will never give me any work. It is not that they don’t want to, but possible assignments depend on relevant needs coming up. From a hard-nosed point of view, as an investment perhaps my effort is not worth it. But I keep in touch because I want to maintain the relationships, not because they might lead to work. I believe that the willingness to meet would soon dry up if people felt I was only there to sell.

I spend quite a lot of my free time supporting my University’s alumni relations. We all know that in the end there is only one reason why universities have become so keen on keeping in touch with alumni recently. They want our money.

However, donations do not just happen. Unless there is an overt exchange (e.g. we will name xxx after you in return), persuading people to give depends on the relationship you have with them. And relationships are really between people, not between people and organisations. I build relationships with fellow alumni through activities we share only because I – and they – value the relationships themselves. If that builds engagement with the University and leads to giving, that’s good, but it is never the point. Indeed, raising the subject of fundraising at all would put some people off engaging, so it is off-limits.

As an interim manager, I rely on networks to find my next assignment. Many of the people in my immediate network I have known for years, but I still make sure I keep in touch. It only needs the occasional coffee, phone call or email. With newer contacts that I know less well, I make more effort to build the relationship.

Most of those people will never give me any work. It is not that they don’t want to, but possible assignments depend on relevant needs coming up. From a hard-nosed point of view, as an investment perhaps my effort is not worth it. But I keep in touch because I want to maintain the relationships, not because they might lead to work. I believe that the willingness to meet would soon dry up if people felt I was only there to sell.

I spend quite a lot of my free time supporting my University’s alumni relations. We all know that in the end there is only one reason why universities have become so keen on keeping in touch with alumni recently. They want our money.

However, donations do not just happen. Unless there is an overt exchange (e.g. we will name xxx after you in return), persuading people to give depends on the relationship you have with them. And relationships are really between people, not between people and organisations. I build relationships with fellow alumni through activities we share only because I – and they – value the relationships themselves. If that builds engagement with the University and leads to giving, that’s good, but it is never the point. Indeed, raising the subject of fundraising at all would put some people off engaging, so it is off-limits.

Relationship building sows seeds

The point of relationship building and maintaining networks is to create a fertile seed-bed for what you hope will germinate in the future. The gardener can dig the soil, add compost, and provide water. He can provide the conditions for successful germination. The miracle of germination though comes from the seeds themselves.

It was only in the latter stages of the referendum campaign that the penny dropped for me. I realised that the reason that the campaign was so much about emotion and so little about facts and likely consequences was that, whatever its ostensible purpose, the referendum had come to be about who we are. My identity is what I believe it to be, and what those I identify with believe it to be. The outcome of a referendum does not, cannot, change that, even if it can lead to a change of status.

It would obviously be nonsense if, when you asked someone whether they would be best off staying married or getting divorced, they stated their gender as the answer. Politicians have allowed a question about relationship to be given an answer about identity. Apples and oranges. In so doing they have shot themselves – and at the same time the whole country – in the foot.

How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

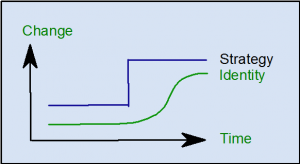

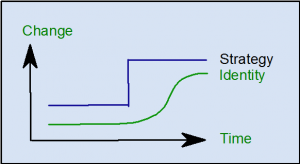

Identity and change

There is a profound lesson about change there. Identity is perhaps the ‘stickiest’ phenomenon in culture, because belonging is so fundamental to our sense of security. A change project is often perceived as changing in some way the identity of that to which we belong. However, peoples’ sense of identity changes much more slowly than the strategy. If we do not take steps to bridge the identity gap while people catch up, it is the relationship which is in for trouble. How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.  Many years ago I used to make pottery as a hobby. After a few years I got to be good enough that friends sometimes asked me to make pots for them. Of course, that is when things start to get a bit difficult – what to charge them? I could have said “I’m a hobby potter – if I cover my costs, that will be fine.” But then, if a friend asked me to make something (in principle at least) it was instead of buying from someone who was trying (and mostly struggling) to make a living out of potting. For someone like me to undercut them seemed wrong. I always charged about what I thought they would have had to pay a ‘real’ potter for something similar. That way I felt that they were choosing my work just because they liked what I made. When I explained, everyone thought that was fair.

Over the years, I have learnt just how important it is to value yourself appropriately. I once took a job at a rather lower salary than I had been used to, rather than continue the uncertainty of searching until I found a better one. I discovered that because I had accepted that valuation of myself, understandably everyone else did too. The job didn’t challenge me, so I got bored, but it seemed to be impossible to persuade anyone within the organisation that I could be adding more value if only they would ask me to work on some more difficult problems – of which there were plenty. The job I was doing needed to be done. Before long, I left to go to a job at a more appropriate level.

This can be a difficult balance for an interim manager. Price is only an imperfect proxy for the value of the job, but what a customer expects to pay is usually a good indication of how they see it. We all need to pay the bills, but accepting a disparity in price perceptions is not usually a good basis for a satisfying relationship in any kind of transaction.

Many years ago I used to make pottery as a hobby. After a few years I got to be good enough that friends sometimes asked me to make pots for them. Of course, that is when things start to get a bit difficult – what to charge them? I could have said “I’m a hobby potter – if I cover my costs, that will be fine.” But then, if a friend asked me to make something (in principle at least) it was instead of buying from someone who was trying (and mostly struggling) to make a living out of potting. For someone like me to undercut them seemed wrong. I always charged about what I thought they would have had to pay a ‘real’ potter for something similar. That way I felt that they were choosing my work just because they liked what I made. When I explained, everyone thought that was fair.

Over the years, I have learnt just how important it is to value yourself appropriately. I once took a job at a rather lower salary than I had been used to, rather than continue the uncertainty of searching until I found a better one. I discovered that because I had accepted that valuation of myself, understandably everyone else did too. The job didn’t challenge me, so I got bored, but it seemed to be impossible to persuade anyone within the organisation that I could be adding more value if only they would ask me to work on some more difficult problems – of which there were plenty. The job I was doing needed to be done. Before long, I left to go to a job at a more appropriate level.

This can be a difficult balance for an interim manager. Price is only an imperfect proxy for the value of the job, but what a customer expects to pay is usually a good indication of how they see it. We all need to pay the bills, but accepting a disparity in price perceptions is not usually a good basis for a satisfying relationship in any kind of transaction.

Near where I live, there is a wonderful cheese shop. It sells an amazing selection of English artisanal cheeses, as well as a variety of other delicious local produce. Not surprisingly, it is my place of choice for cheese for Christmas. It's just a pity that the customer service is not up to the standard of the cheese.

I placed my order in good time, for collection on 23 December. I duly arrived at the shop, full of anticipation, on my way home from work. The table outside groaned with goodies including beautifully-decorated cakes, rustic breads and colourful preserves. The shop is fairly simple inside, but filled with the wonderful aroma from the cheeses and from the delicious food being served in their upstairs café.

There seemed only to be one young lady serving, and she looked a bit stressed by the queue of customers; cutting, weighing and wrapping cheeses is a slow process. Still, I assumed serving me would be easy – all that should have been done already. She looked in the fridges under the cool counter; not there. She looked in another fridge; no better. Looking more stressed, she told me that she was very sorry, she couldn’t find my order; “Would you mind going away and coming back later?”

Bad move. “Yes, actually, I would. I’m on my way home from work, I've had a busy day, and I don’t want to hang around. That’s why I placed an order.” Another hunt still produced nothing.

A small lady with shoulder-length reddish hair came in – the manager. We found where my order had been written in the book, just as I had said. “Well, if you can wait, we can make up some of your order again, but I’m afraid we have none of the Tamworth left. We are completely sold out of soft cheeses.” I grumpily agreed that they had better do that, meanwhile starting to wonder where I would be able to find a good soft cheese on Christmas Eve. Then she showed me a small cheese –under 100g I would say – and said “we have one of these left. They are absolutely delicious – unfortunately I can’t give you a taste as it is the last one. They are £6.” … So that is about £60 / kg? Are you serious? No thanks.

After that, the manager lost interest. The assistant worked out the total price, and only then said “we’ll give you 10% off for the inconvenience”. I paid, and walked out with my cheese, about 20 minutes later than I had expected and in a thoroughly bad temper.

So what did I learn from these unhappy events? Observing my own feelings, first, that the longer the problem lasts, the more it takes to put it right. And second, that if you don’t do enough, you might as well do nothing.

Good customer service

The first rule of customer service is “keep your promises”. And since things will sometimes go wrong, the second rule is “When you can’t keep your promises, try to solve the problem you have caused as quickly as you can”. If the assistant had said at the start something like, “I’m really sorry, I’ll make the order up as quickly as I can. You can have a free coffee upstairs while you are waiting. What can I offer you instead of the Tamworth?” – suggesting solutions to my problems – I would probably have been satisfied, and would actually have spent more. By the time the manager showed me the expensive cheese, she needed to have given it to me, not offered to sell it to me, to compensate. And by the end, a 10% discount not only did not solve my problem but felt like adding insult to injury. A customer problem is an opportunity for free good – or bad – publicity. The choice of which is yours. [contact-form][contact-field label='Name' type='name' required='1'/][contact-field label='Email' type='email' required='1'/][contact-field label='Website' type='url'/][contact-field label='Comment' type='textarea' required='1'/][/contact-form]

Coming home from work the other day I saw a poster on the Tube which grabbed my attention. Leaving out the unnecessary details, it said

“Buy a ……, get a free …… worth £49!”

Is it really? Value, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. The company may choose to sell the gadget for £49 normally, but that certainly does not mean it is worth £49 to me. In fact, it almost certainly isn’t – it might be worth more, in which case even if I had to pay for it I would think I was getting a good deal (and I may well have already bought one anyway), or it is worth less, in which case I’d never buy one normally, but might be tempted to get one for nothing. It is pretty unlikely that they have hit on exactly the right value for me.

Our entire economic system is based on the idea that things have different values to different people. That is how trade works – if it were not like that, it would be impossible to make a profit on trading, so there would be no incentive to do so. I buy something because it is worth more to me to have the thing than the money. The seller sells it because they value having the money more than the thing. It may be in the trader’s interests to confuse value with price, but in the end we all make our own judgements about what something is worth to us.

[contact-form][contact-field label='Name' type='name' required='1'/][contact-field label='Email' type='email' required='1'/][contact-field label='Website' type='url'/][contact-field label='Comment' type='textarea' required='1'/][/contact-form]

[caption id="" align="alignright" width="240"] Central London Traffic (Photo credit: oatsy40)[/caption]

Driving through London a day or two ago, I was amazed to see in front of me an advertising van unlike any I had ever seen before. Half of the back of the van was taken up with a large screen, repeatedly showing a short advertising video clip, obviously in full view of the drivers behind. It certainly got my attention!

Call me old-fashioned, but this seemed to me to be an innovation too far. Driving in London is hard enough, with heavy traffic, bicycles, pedestrians, buses stopping and starting, complex road layouts etc. to pay attention to, without adding advertising which is so clearly going to distract drivers. Health and Safety rules have a bad reputation, but this seemed to me to be something they really should apply to.

But it did remind me that if you want something to grab someone’s attention, you should make it move! Years ago (even before the first PCs), I was a University Lecturer, and had to put on a display of some research for an open day. Nearly all the displays people made were static. Even though my subject was hard to make exciting for the public, and though my animated display on an early computer screen was small and very crude (in those days anything more would have been very hard), the fact that it moved and had a very simple coordinated sound track attracted far more visitors than most other displays.

Central London Traffic (Photo credit: oatsy40)[/caption]

Driving through London a day or two ago, I was amazed to see in front of me an advertising van unlike any I had ever seen before. Half of the back of the van was taken up with a large screen, repeatedly showing a short advertising video clip, obviously in full view of the drivers behind. It certainly got my attention!

Call me old-fashioned, but this seemed to me to be an innovation too far. Driving in London is hard enough, with heavy traffic, bicycles, pedestrians, buses stopping and starting, complex road layouts etc. to pay attention to, without adding advertising which is so clearly going to distract drivers. Health and Safety rules have a bad reputation, but this seemed to me to be something they really should apply to.

But it did remind me that if you want something to grab someone’s attention, you should make it move! Years ago (even before the first PCs), I was a University Lecturer, and had to put on a display of some research for an open day. Nearly all the displays people made were static. Even though my subject was hard to make exciting for the public, and though my animated display on an early computer screen was small and very crude (in those days anything more would have been very hard), the fact that it moved and had a very simple coordinated sound track attracted far more visitors than most other displays.

Central London Traffic (Photo credit: oatsy40)[/caption]

Driving through London a day or two ago, I was amazed to see in front of me an advertising van unlike any I had ever seen before. Half of the back of the van was taken up with a large screen, repeatedly showing a short advertising video clip, obviously in full view of the drivers behind. It certainly got my attention!

Call me old-fashioned, but this seemed to me to be an innovation too far. Driving in London is hard enough, with heavy traffic, bicycles, pedestrians, buses stopping and starting, complex road layouts etc. to pay attention to, without adding advertising which is so clearly going to distract drivers. Health and Safety rules have a bad reputation, but this seemed to me to be something they really should apply to.

But it did remind me that if you want something to grab someone’s attention, you should make it move! Years ago (even before the first PCs), I was a University Lecturer, and had to put on a display of some research for an open day. Nearly all the displays people made were static. Even though my subject was hard to make exciting for the public, and though my animated display on an early computer screen was small and very crude (in those days anything more would have been very hard), the fact that it moved and had a very simple coordinated sound track attracted far more visitors than most other displays.

Central London Traffic (Photo credit: oatsy40)[/caption]

Driving through London a day or two ago, I was amazed to see in front of me an advertising van unlike any I had ever seen before. Half of the back of the van was taken up with a large screen, repeatedly showing a short advertising video clip, obviously in full view of the drivers behind. It certainly got my attention!

Call me old-fashioned, but this seemed to me to be an innovation too far. Driving in London is hard enough, with heavy traffic, bicycles, pedestrians, buses stopping and starting, complex road layouts etc. to pay attention to, without adding advertising which is so clearly going to distract drivers. Health and Safety rules have a bad reputation, but this seemed to me to be something they really should apply to.

But it did remind me that if you want something to grab someone’s attention, you should make it move! Years ago (even before the first PCs), I was a University Lecturer, and had to put on a display of some research for an open day. Nearly all the displays people made were static. Even though my subject was hard to make exciting for the public, and though my animated display on an early computer screen was small and very crude (in those days anything more would have been very hard), the fact that it moved and had a very simple coordinated sound track attracted far more visitors than most other displays.

Change gets peoples' attention!

Change is like that too. It moves, so it gets peoples' attention, unfortunately more often negatively than positively – like the advertising van did for me. But if you can find a way to make people curious, and if possible engage them in the exploration of the change, the results can be quite different!

[caption id="" align="alignright" width="300"] English: Terraced house façades, Montague Street See also 1608624 (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

I’ll never forget my first serious experience of negotiation.

I was selling my first house, a small, terraced house in a cheap part of the city. I loved it, because it was the first house I had owned, and because I had put a lot of work – and a lot of myself – into it. I had decorated every room; I had refitted the kitchen; I had installed central heating to replace electric storage heaters. I was moving to a new area, where I knew housing was going to be a lot more expensive.

I had received an offer to buy my house from a junior colleague at work. Obviously that made things slightly awkward to start with. But I was unprepared for what happened when he asked if he could visit again, with a family friend.

They duly arrived, and I showed them around. The family friend, an older gentleman, was very appreciative, admiring everything I had done, complimenting me on my workmanship, and so on. And then, at the end of the visit, he pitched me a new price, substantially lower than the offer my colleague had previously made. I was caught off guard. Having refused the new price, I felt I had to respond to his questions, starting with what was the lowest price I would accept? He came back with requests to throw in this and that if they agreed to a higher price, and so on. We eventually agreed a deal – which actually was not such a bad deal from my point of view – but I was left feeling bruised.

Looking back, I have to admire the technique. All the praise, all the efforts to make me feel good first, worked a treat, and there was nothing in the negotiation itself that I could criticise. He did a good job for my colleague. So why did I feel bruised?

The one thing that was missing in the exchange was creating an honest expectation. I had been led to believe that the friend was there to give a second opinion. It was my colleague’s first house purchase, just as it had been mine, so understandably he wanted someone else to endorse his judgement. I had not expected that the friend was there to negotiate on his behalf – after all, an offer had already been made. Perhaps I was a bit naïve, but I was caught unprepared; the negotiation had high financial and emotional value for me, and I had no experience of handling something like that. I felt that I was backed into a corner, and that personal trust had been breached.

So what is the lesson? Don’t just play fair – make sure everyone knows what game you are going to be playing beforehand, especially if personal relationships are involved. Trust is too important, and too hard to rebuild, to risk losing.

English: Terraced house façades, Montague Street See also 1608624 (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

I’ll never forget my first serious experience of negotiation.

I was selling my first house, a small, terraced house in a cheap part of the city. I loved it, because it was the first house I had owned, and because I had put a lot of work – and a lot of myself – into it. I had decorated every room; I had refitted the kitchen; I had installed central heating to replace electric storage heaters. I was moving to a new area, where I knew housing was going to be a lot more expensive.

I had received an offer to buy my house from a junior colleague at work. Obviously that made things slightly awkward to start with. But I was unprepared for what happened when he asked if he could visit again, with a family friend.

They duly arrived, and I showed them around. The family friend, an older gentleman, was very appreciative, admiring everything I had done, complimenting me on my workmanship, and so on. And then, at the end of the visit, he pitched me a new price, substantially lower than the offer my colleague had previously made. I was caught off guard. Having refused the new price, I felt I had to respond to his questions, starting with what was the lowest price I would accept? He came back with requests to throw in this and that if they agreed to a higher price, and so on. We eventually agreed a deal – which actually was not such a bad deal from my point of view – but I was left feeling bruised.

Looking back, I have to admire the technique. All the praise, all the efforts to make me feel good first, worked a treat, and there was nothing in the negotiation itself that I could criticise. He did a good job for my colleague. So why did I feel bruised?

The one thing that was missing in the exchange was creating an honest expectation. I had been led to believe that the friend was there to give a second opinion. It was my colleague’s first house purchase, just as it had been mine, so understandably he wanted someone else to endorse his judgement. I had not expected that the friend was there to negotiate on his behalf – after all, an offer had already been made. Perhaps I was a bit naïve, but I was caught unprepared; the negotiation had high financial and emotional value for me, and I had no experience of handling something like that. I felt that I was backed into a corner, and that personal trust had been breached.

So what is the lesson? Don’t just play fair – make sure everyone knows what game you are going to be playing beforehand, especially if personal relationships are involved. Trust is too important, and too hard to rebuild, to risk losing.

English: Terraced house façades, Montague Street See also 1608624 (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

I’ll never forget my first serious experience of negotiation.

I was selling my first house, a small, terraced house in a cheap part of the city. I loved it, because it was the first house I had owned, and because I had put a lot of work – and a lot of myself – into it. I had decorated every room; I had refitted the kitchen; I had installed central heating to replace electric storage heaters. I was moving to a new area, where I knew housing was going to be a lot more expensive.

I had received an offer to buy my house from a junior colleague at work. Obviously that made things slightly awkward to start with. But I was unprepared for what happened when he asked if he could visit again, with a family friend.

They duly arrived, and I showed them around. The family friend, an older gentleman, was very appreciative, admiring everything I had done, complimenting me on my workmanship, and so on. And then, at the end of the visit, he pitched me a new price, substantially lower than the offer my colleague had previously made. I was caught off guard. Having refused the new price, I felt I had to respond to his questions, starting with what was the lowest price I would accept? He came back with requests to throw in this and that if they agreed to a higher price, and so on. We eventually agreed a deal – which actually was not such a bad deal from my point of view – but I was left feeling bruised.

Looking back, I have to admire the technique. All the praise, all the efforts to make me feel good first, worked a treat, and there was nothing in the negotiation itself that I could criticise. He did a good job for my colleague. So why did I feel bruised?

The one thing that was missing in the exchange was creating an honest expectation. I had been led to believe that the friend was there to give a second opinion. It was my colleague’s first house purchase, just as it had been mine, so understandably he wanted someone else to endorse his judgement. I had not expected that the friend was there to negotiate on his behalf – after all, an offer had already been made. Perhaps I was a bit naïve, but I was caught unprepared; the negotiation had high financial and emotional value for me, and I had no experience of handling something like that. I felt that I was backed into a corner, and that personal trust had been breached.

So what is the lesson? Don’t just play fair – make sure everyone knows what game you are going to be playing beforehand, especially if personal relationships are involved. Trust is too important, and too hard to rebuild, to risk losing.

English: Terraced house façades, Montague Street See also 1608624 (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

I’ll never forget my first serious experience of negotiation.

I was selling my first house, a small, terraced house in a cheap part of the city. I loved it, because it was the first house I had owned, and because I had put a lot of work – and a lot of myself – into it. I had decorated every room; I had refitted the kitchen; I had installed central heating to replace electric storage heaters. I was moving to a new area, where I knew housing was going to be a lot more expensive.

I had received an offer to buy my house from a junior colleague at work. Obviously that made things slightly awkward to start with. But I was unprepared for what happened when he asked if he could visit again, with a family friend.

They duly arrived, and I showed them around. The family friend, an older gentleman, was very appreciative, admiring everything I had done, complimenting me on my workmanship, and so on. And then, at the end of the visit, he pitched me a new price, substantially lower than the offer my colleague had previously made. I was caught off guard. Having refused the new price, I felt I had to respond to his questions, starting with what was the lowest price I would accept? He came back with requests to throw in this and that if they agreed to a higher price, and so on. We eventually agreed a deal – which actually was not such a bad deal from my point of view – but I was left feeling bruised.

Looking back, I have to admire the technique. All the praise, all the efforts to make me feel good first, worked a treat, and there was nothing in the negotiation itself that I could criticise. He did a good job for my colleague. So why did I feel bruised?

The one thing that was missing in the exchange was creating an honest expectation. I had been led to believe that the friend was there to give a second opinion. It was my colleague’s first house purchase, just as it had been mine, so understandably he wanted someone else to endorse his judgement. I had not expected that the friend was there to negotiate on his behalf – after all, an offer had already been made. Perhaps I was a bit naïve, but I was caught unprepared; the negotiation had high financial and emotional value for me, and I had no experience of handling something like that. I felt that I was backed into a corner, and that personal trust had been breached.

So what is the lesson? Don’t just play fair – make sure everyone knows what game you are going to be playing beforehand, especially if personal relationships are involved. Trust is too important, and too hard to rebuild, to risk losing.