Just before Christmas, I was doing some last-minute shopping in one of the Oxford Street department stores. As usual at that time of year, there was a long queue for the checkouts. When I eventually got to a till, I was surprised to see two people there. There was a young man operating the till. And there was a tall older man bagging the goods sold. Although they were busy, you could tell that they were working well together, and enjoying exchanging a few words with customers and each other when they could.

Despite this, the older man had a gravitas that you associate more with the Board room than with the tills of a busy store. Not surprising really – he was a senior manager doing a shift supporting the front-line staff at their busiest time. What was surprising (apart from him being there at all) was the easy way he appeared to be accepted as part of the team.

Here was a real “one-team” culture in action. He was not just doing what the organisation expected. He was doing what he believed in, and so it came naturally. His colleagues saw it as perfectly natural and normal too. Everyone was comfortable, and it worked.

Culture is the pattern of behaviours that people adopt in order to be accepted in a community. It is defined by what people really value, not what they say they value. In that store, people really valued working together as one team to deliver happy customers. That meant that there was nothing awkward about managers working on the tills. Actions speak louder than words, and clearly it works for them.

Just before Christmas, I was doing some last-minute shopping in one of the Oxford Street department stores. As usual at that time of year, there was a long queue for the checkouts. When I eventually got to a till, I was surprised to see two people there. There was a young man operating the till. And there was a tall older man bagging the goods sold. Although they were busy, you could tell that they were working well together, and enjoying exchanging a few words with customers and each other when they could.

Despite this, the older man had a gravitas that you associate more with the Board room than with the tills of a busy store. Not surprising really – he was a senior manager doing a shift supporting the front-line staff at their busiest time. What was surprising (apart from him being there at all) was the easy way he appeared to be accepted as part of the team.

Here was a real “one-team” culture in action. He was not just doing what the organisation expected. He was doing what he believed in, and so it came naturally. His colleagues saw it as perfectly natural and normal too. Everyone was comfortable, and it worked.

Culture is the pattern of behaviours that people adopt in order to be accepted in a community. It is defined by what people really value, not what they say they value. In that store, people really valued working together as one team to deliver happy customers. That meant that there was nothing awkward about managers working on the tills. Actions speak louder than words, and clearly it works for them.

Walking the Talk

That experience prompted me to re-read Carolyn Taylor’s “Walking the Talk”, an excellent introduction to corporate culture. Here was an organisation that has a clearly-defined culture, and knows how to maintain it by walking the talk. Sadly, in my experience most leaders are better at the talking than the walking, and in any case most organisations don’t really know what culture they want (if they think about it at all). That’s a lot of value to be losing.

Last week I attended the inaugural meeting of the Change Management Institute’s Thought Leadership Panel. Getting a group of senior practitioners together is always interesting. I’m sure that if we hadn’t all had other things to do the conversation could have gone on a long time!

I have been thinking some more about two related questions which we didn’t have time to explore very far. What makes a change manager? And why do so many senior leaders struggle to ‘get’ how change management works?

Perhaps the best starting point for thinking about what makes a change manager is to look at people who are change managers and consider how they got there. The first thing that is clear is that they come from a wide variety of different backgrounds. Indeed, many change managers have done a wide variety of different things in their careers. That was certainly true of those present last week. All of that suggests that there is no standard model. A good change leader probably takes advantage of having a wide variety of experience and examples to draw on - stories to tell, if you will. Where those experiences come from is less important.

Then there is a tension between two different kinds of approach. Change managers have to be project managers to get things done. But change is not like most projects: there is a limit to how far you can push the pace (and still have the change stick) because that depends on changing the mindsets of people affected. Thumping the table or throwing money at it hardly ever speeds that up. Successful change managers moderate the push for quick results with a sensitivity to how those people are reacting. Not all project managers can do that.

So I think you need three main ingredients for a successful change leader:

- The analytical and planning skills to manage projects;

- The people skills to listen and to influence and manage accordingly;

- Enough varied experiences to draw on to be able to tell helpful stories from similar situations.

Senior managers and change

Why do many senior managers struggle to understand the change process? They may well have the same basic skills, but the blending is usually more focused on results than on process. That is not surprising; their jobs depend on delivering results. A pure ‘results’ focus may be OK to run a stable operation. Problems are likely to arise when change is required if the process component is too limited. Delivering change successfully usually depends on the senior managers as well as the change manager understanding that difference.

It was only in the latter stages of the referendum campaign that the penny dropped for me. I realised that the reason that the campaign was so much about emotion and so little about facts and likely consequences was that, whatever its ostensible purpose, the referendum had come to be about who we are. My identity is what I believe it to be, and what those I identify with believe it to be. The outcome of a referendum does not, cannot, change that, even if it can lead to a change of status.

It would obviously be nonsense if, when you asked someone whether they would be best off staying married or getting divorced, they stated their gender as the answer. Politicians have allowed a question about relationship to be given an answer about identity. Apples and oranges. In so doing they have shot themselves – and at the same time the whole country – in the foot.

How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

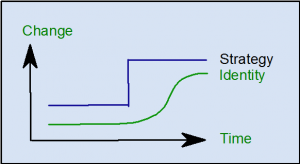

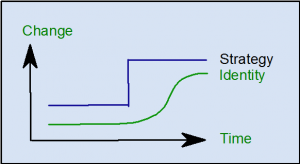

Identity and change

There is a profound lesson about change there. Identity is perhaps the ‘stickiest’ phenomenon in culture, because belonging is so fundamental to our sense of security. A change project is often perceived as changing in some way the identity of that to which we belong. However, peoples’ sense of identity changes much more slowly than the strategy. If we do not take steps to bridge the identity gap while people catch up, it is the relationship which is in for trouble. How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.  A long time ago, I proposed an important change to a committee of senior colleagues. The overall intent was hardly arguable, and I had carefully thought out the details. Overall, it got a good hearing. But then the trouble started. One manager picked on a point of detail which he didn’t like. OK, I thought, I can find a way round that. But then other managers piled in, some supporting my position on that, but objecting to different details. The discussion descended into a squabble about detailed points on which no-one could agree, and as a result the whole project was shelved despite its overall merits.

I learnt an important lesson from that experience. When a collective decision is required, detail is your enemy. Most projects will have – or at least may be perceived to have – some negative impacts on some people, even though overall they benefit everyone. Maybe someone loses autonomy in some area, or needs to loan some staff. Maybe there is some overlap with a pet project of their own. Whatever the reason, providing detail at the outset makes those losses visible, and can lead to opposition based on self-interest (even if that is well-concealed) which kills the whole project. As we all know, you can’t negotiate with a committee.

So what is the answer? The approach I have found works best is to start by seeking agreement for general principles with which the implementation must be consistent. The absence of detail means that the eventual impacts on individual colleagues are uncertain, and consequently the discussion is more likely to stay focused on the bigger picture. Ideally you are given authority to implement within the approved principles. But even if you have to go back with a detailed plan, once the committee has approved the outcome and the principles to be followed it is much harder for them to reject a solution that sticks to those, let alone to kill the project.

Looking at the wider world, perhaps the Ten Commandments of the Bible provide a good example of this approach. For a more business-relevant example, see my earlier posts on the principles behind good internal governance.

More generally, defining top-level principles is also the key to delegating decision-making to local managers. It means that they can make decisions which take proper account of local conditions, while ensuring that decisions made by different managers in different areas all have an underlying consistency.

A long time ago, I proposed an important change to a committee of senior colleagues. The overall intent was hardly arguable, and I had carefully thought out the details. Overall, it got a good hearing. But then the trouble started. One manager picked on a point of detail which he didn’t like. OK, I thought, I can find a way round that. But then other managers piled in, some supporting my position on that, but objecting to different details. The discussion descended into a squabble about detailed points on which no-one could agree, and as a result the whole project was shelved despite its overall merits.

I learnt an important lesson from that experience. When a collective decision is required, detail is your enemy. Most projects will have – or at least may be perceived to have – some negative impacts on some people, even though overall they benefit everyone. Maybe someone loses autonomy in some area, or needs to loan some staff. Maybe there is some overlap with a pet project of their own. Whatever the reason, providing detail at the outset makes those losses visible, and can lead to opposition based on self-interest (even if that is well-concealed) which kills the whole project. As we all know, you can’t negotiate with a committee.

So what is the answer? The approach I have found works best is to start by seeking agreement for general principles with which the implementation must be consistent. The absence of detail means that the eventual impacts on individual colleagues are uncertain, and consequently the discussion is more likely to stay focused on the bigger picture. Ideally you are given authority to implement within the approved principles. But even if you have to go back with a detailed plan, once the committee has approved the outcome and the principles to be followed it is much harder for them to reject a solution that sticks to those, let alone to kill the project.

Looking at the wider world, perhaps the Ten Commandments of the Bible provide a good example of this approach. For a more business-relevant example, see my earlier posts on the principles behind good internal governance.

More generally, defining top-level principles is also the key to delegating decision-making to local managers. It means that they can make decisions which take proper account of local conditions, while ensuring that decisions made by different managers in different areas all have an underlying consistency.

I’ve recently started taking singing lessons. A bit late, you might say, since I have been singing in choirs for decades, and I certainly wish I’d started sooner. But it has taught me something important about how we learn.

I have been surprised to discover that almost none of my lesson time is about singing in tune or in time! Everything is about technique – how you breath, how you pronounce the words – and a lot of my practice is just saying the words, not singing them at all. It is really hard to train your body to work in a very particular way: months or years of lessons, hours and hours of practice. You can’t just be told the right way to do it, and go away and then do it right - it is more like learning to drive than learning to pass an academic exam. And sometimes you have to be told something over and over again before you are ready to absorb it.

I have taken away three wider lessons:

• What you have to do to learn a new skill may be quite different from what you expected;

• Results may take a long time and demand considerable perseverance; there are no short-cuts;

• Hearing something is not enough – you have to hear it at the right time.

That has made me think about the problems of change in a different way. As an example, one of my clients has many junior and middle managers with a fairly low level of financial understanding, and with commercial pressure continually increasing this is holding them back. How should we fix this? The traditional approach would probably be to send them on a short course to learn the “facts” about finance – understanding a P&L, a balance sheet, etc. But perhaps it is not the facts but the practice they are short of, or they are not ready to hear the message? I have done enough short courses myself to know that few of the facts stay in the mind for long anyway. The singing lessons experience suggests to me that they are probably only part of the solution.

Time to think about a new approach, based on how we learn!

A couple of weeks ago, I had an evening out at the opera. I’d never encountered this on previous visits, but throughout the performance, there was a lady at the side of the stage translating the sung words into sign language. At the time I thought it rather odd – why would deaf people come to the opera at all? In any case, the words were displayed in English text over the top of the stage. Was this accessibility gone mad?

That prompted me to do a little research, and to realise that there are many reasons why there might be deaf people in the audience: from the obvious-if-you-think-about-it possibility that they might be with partners who are not deaf, to the much more important facts that most deaf people have some hearing and may well enjoy music (and even if they have no hearing, may find musical enjoyment in feeling the vibrations), and the more profound realisation that for some deaf people the English spoken and written around them may be ‘foreign’ compared to sign language.

Assumptions

All too often, we make assumptions about how other people see things. In this case, the conflict between my assumptions and the evidence led me to investigate, and find out that my assumptions were wrong, but much of the time our assumptions go unchallenged, and so un-investigated. In change projects, this is a particular danger. People who are feeling threatened or alienated by a change may be unwilling to point out that wrong assumptions are being made, even if they are not assuming that “management must have thought of that – it’s not for me to say”. Change managers must try to unearth conflicts like this by building relationships widely, and giving people at all levels encouragement to bring their concerns into the open. Change projects often fail, at least to some degree. I wonder how often that is because the manager did not realise, or bother to find out why, the assumptions were in conflict with the evidence. [contact-form][contact-field label='Name' type='name' required='1'/][contact-field label='Email' type='email' required='1'/][contact-field label='Website' type='url'/][contact-field label='Comment' type='textarea' required='1'/][/contact-form]

The unexpected death this week of Bob Crow, leader of the RMT Union (which represents many London Underground train drivers amongst others) has prompted quite a bit of media comment over the last few days. Tributes from industrial and political leaders have expressed sincere sadness, despite what his militant public persona might have led you to expect.

I never met Bob Crow, but it seems to me that he grasped more clearly than many that what most people want in their leaders is passion and an appeal to their emotions. At a time of generally falling Union membership, he doubled RMT membership, and then doubled it again, over a decade. I doubt that he could have done that by making a careful rational case. Stack that up against managers who – as public servants, charged with careful management of public money – are obliged to make their arguments rationally. Can you imagine what would have happened if politicians had incited Londoners to picket RMT headquarters when the tube went on strike? It is hardly surprising that he made an impact.

Recalling other powerful Union figures of the past – Arthur Scargill, say - isn’t that instinctive understanding of emotional leadership and the power of passion something they had in common? And perhaps the reason we now have a much less unionised and strike-prone world than we did is in part because union leaders have become less demonstrably passionate.

We need leaders who are passionate about their cause – whether in politics, in industry, or in unions – because passion is what galvanises the led. Whichever side of the argument you are on, we need more leaders who do that, as Bob Crow did.

[contact-form][contact-field label='Name' type='name' required='1'/][contact-field label='Email' type='email' required='1'/][contact-field label='Website' type='url'/][contact-field label='Comment' type='textarea' required='1'/][/contact-form]

There you are, head down in a report, a spreadsheet, or some other urgent bit of business. There’s a knock, and your mind returns to your desk from miles away. Someone says they have a problem and can they talk it over with you please? An interruption. What are you going to say?

Your work is high-value, it takes real concentration, and you need to keep your focus to get it done right. On the other hand, if you send them away, you may be telling them that you do not value them and what they do.

Of course my own work seems urgent, but I know I’ll get it done one way or another. My colleague on the other hand is important, because it is essential for the longer term that they feel valued. I could easily – and quickly – damage a relationship I have taken a long time to build. I know they would not interrupt me when I’m busy unless they felt it was important. It is really important to give them something to show that I’m taking them seriously.

Even if I decide I can only spare 5 minutes now, I’ll always offer that as a first step, at least to give them things to be thinking about until I can pay full attention. If I give them proper respect, value them, take their problems seriously, I find that they respect me back – and interruption is rare unless it really is necessary.

So if you really can't deal with the interruption fully there and then, at least find some compromise. It will pay you back in the long run.

There you are, head down in a report, a spreadsheet, or some other urgent bit of business. There’s a knock, and your mind returns to your desk from miles away. Someone says they have a problem and can they talk it over with you please? An interruption. What are you going to say?

Your work is high-value, it takes real concentration, and you need to keep your focus to get it done right. On the other hand, if you send them away, you may be telling them that you do not value them and what they do.

Of course my own work seems urgent, but I know I’ll get it done one way or another. My colleague on the other hand is important, because it is essential for the longer term that they feel valued. I could easily – and quickly – damage a relationship I have taken a long time to build. I know they would not interrupt me when I’m busy unless they felt it was important. It is really important to give them something to show that I’m taking them seriously.

Even if I decide I can only spare 5 minutes now, I’ll always offer that as a first step, at least to give them things to be thinking about until I can pay full attention. If I give them proper respect, value them, take their problems seriously, I find that they respect me back – and interruption is rare unless it really is necessary.

So if you really can't deal with the interruption fully there and then, at least find some compromise. It will pay you back in the long run.  I have been reading

I have been reading