Many years ago I used to make pottery as a hobby. After a few years I got to be good enough that friends sometimes asked me to make pots for them. Of course, that is when things start to get a bit difficult – what to charge them? I could have said “I’m a hobby potter – if I cover my costs, that will be fine.” But then, if a friend asked me to make something (in principle at least) it was instead of buying from someone who was trying (and mostly struggling) to make a living out of potting. For someone like me to undercut them seemed wrong. I always charged about what I thought they would have had to pay a ‘real’ potter for something similar. That way I felt that they were choosing my work just because they liked what I made. When I explained, everyone thought that was fair.

Over the years, I have learnt just how important it is to value yourself appropriately. I once took a job at a rather lower salary than I had been used to, rather than continue the uncertainty of searching until I found a better one. I discovered that because I had accepted that valuation of myself, understandably everyone else did too. The job didn’t challenge me, so I got bored, but it seemed to be impossible to persuade anyone within the organisation that I could be adding more value if only they would ask me to work on some more difficult problems – of which there were plenty. The job I was doing needed to be done. Before long, I left to go to a job at a more appropriate level.

This can be a difficult balance for an interim manager. Price is only an imperfect proxy for the value of the job, but what a customer expects to pay is usually a good indication of how they see it. We all need to pay the bills, but accepting a disparity in price perceptions is not usually a good basis for a satisfying relationship in any kind of transaction.

Many years ago I used to make pottery as a hobby. After a few years I got to be good enough that friends sometimes asked me to make pots for them. Of course, that is when things start to get a bit difficult – what to charge them? I could have said “I’m a hobby potter – if I cover my costs, that will be fine.” But then, if a friend asked me to make something (in principle at least) it was instead of buying from someone who was trying (and mostly struggling) to make a living out of potting. For someone like me to undercut them seemed wrong. I always charged about what I thought they would have had to pay a ‘real’ potter for something similar. That way I felt that they were choosing my work just because they liked what I made. When I explained, everyone thought that was fair.

Over the years, I have learnt just how important it is to value yourself appropriately. I once took a job at a rather lower salary than I had been used to, rather than continue the uncertainty of searching until I found a better one. I discovered that because I had accepted that valuation of myself, understandably everyone else did too. The job didn’t challenge me, so I got bored, but it seemed to be impossible to persuade anyone within the organisation that I could be adding more value if only they would ask me to work on some more difficult problems – of which there were plenty. The job I was doing needed to be done. Before long, I left to go to a job at a more appropriate level.

This can be a difficult balance for an interim manager. Price is only an imperfect proxy for the value of the job, but what a customer expects to pay is usually a good indication of how they see it. We all need to pay the bills, but accepting a disparity in price perceptions is not usually a good basis for a satisfying relationship in any kind of transaction.

A couple of weeks ago, I had an evening out at the opera. I’d never encountered this on previous visits, but throughout the performance, there was a lady at the side of the stage translating the sung words into sign language. At the time I thought it rather odd – why would deaf people come to the opera at all? In any case, the words were displayed in English text over the top of the stage. Was this accessibility gone mad?

That prompted me to do a little research, and to realise that there are many reasons why there might be deaf people in the audience: from the obvious-if-you-think-about-it possibility that they might be with partners who are not deaf, to the much more important facts that most deaf people have some hearing and may well enjoy music (and even if they have no hearing, may find musical enjoyment in feeling the vibrations), and the more profound realisation that for some deaf people the English spoken and written around them may be ‘foreign’ compared to sign language.

Assumptions

All too often, we make assumptions about how other people see things. In this case, the conflict between my assumptions and the evidence led me to investigate, and find out that my assumptions were wrong, but much of the time our assumptions go unchallenged, and so un-investigated. In change projects, this is a particular danger. People who are feeling threatened or alienated by a change may be unwilling to point out that wrong assumptions are being made, even if they are not assuming that “management must have thought of that – it’s not for me to say”. Change managers must try to unearth conflicts like this by building relationships widely, and giving people at all levels encouragement to bring their concerns into the open. Change projects often fail, at least to some degree. I wonder how often that is because the manager did not realise, or bother to find out why, the assumptions were in conflict with the evidence. [contact-form][contact-field label='Name' type='name' required='1'/][contact-field label='Email' type='email' required='1'/][contact-field label='Website' type='url'/][contact-field label='Comment' type='textarea' required='1'/][/contact-form] What do you think when someone offers you something for nothing? I suspect most of us say thank you very much, put it in our pocket or bag … and then often forget about it. The problem is, when we give nothing for it, we tend not to value what we received.

Many years ago I was involved with promoting amateur music events. Sometimes there were few costs to cover, and the main aim was to attract a reasonable audience, so an easy option was to make admission to a concert free. What happens if you do that? You often get a smaller audience than if you sell tickets at a low price!

Why should that be? Well, put yourself in the shoes of the punter. You see a poster advertising a free concert, which looks interesting, so you make a mental note. Come the day of the concert, chances are you have either forgotten about it, or something else more attractive has come along. Since you have invested nothing, you choose to do the more attractive option. Because the organisers have not made you put a value on the event, you may treat it as being worth nothing, unless something else gives it value for you (for example you know one of the performers). There is little difference between something for nothing and nothing for nothing.

On the other hand, if you have to buy a ticket, even for a nominal sum, you must give the event a positive value. In addition, if you have to buy the ticket beforehand, you have made an emotional investment. You are more likely to remember about it, and less likely to decide to do something else.

Luxury brands do something similar but in reverse. The product itself may not be objectively any better than something cheaper, but the value people put on it is higher, so they are willing to pay more.

Value has a significant emotional component, so pricing is always partly a decision about emotion. Never undervalue that!

What do you think when someone offers you something for nothing? I suspect most of us say thank you very much, put it in our pocket or bag … and then often forget about it. The problem is, when we give nothing for it, we tend not to value what we received.

Many years ago I was involved with promoting amateur music events. Sometimes there were few costs to cover, and the main aim was to attract a reasonable audience, so an easy option was to make admission to a concert free. What happens if you do that? You often get a smaller audience than if you sell tickets at a low price!

Why should that be? Well, put yourself in the shoes of the punter. You see a poster advertising a free concert, which looks interesting, so you make a mental note. Come the day of the concert, chances are you have either forgotten about it, or something else more attractive has come along. Since you have invested nothing, you choose to do the more attractive option. Because the organisers have not made you put a value on the event, you may treat it as being worth nothing, unless something else gives it value for you (for example you know one of the performers). There is little difference between something for nothing and nothing for nothing.

On the other hand, if you have to buy a ticket, even for a nominal sum, you must give the event a positive value. In addition, if you have to buy the ticket beforehand, you have made an emotional investment. You are more likely to remember about it, and less likely to decide to do something else.

Luxury brands do something similar but in reverse. The product itself may not be objectively any better than something cheaper, but the value people put on it is higher, so they are willing to pay more.

Value has a significant emotional component, so pricing is always partly a decision about emotion. Never undervalue that!

[caption id="" align="alignright" width="300"] English: Terraced house façades, Montague Street See also 1608624 (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

I’ll never forget my first serious experience of negotiation.

I was selling my first house, a small, terraced house in a cheap part of the city. I loved it, because it was the first house I had owned, and because I had put a lot of work – and a lot of myself – into it. I had decorated every room; I had refitted the kitchen; I had installed central heating to replace electric storage heaters. I was moving to a new area, where I knew housing was going to be a lot more expensive.

I had received an offer to buy my house from a junior colleague at work. Obviously that made things slightly awkward to start with. But I was unprepared for what happened when he asked if he could visit again, with a family friend.

They duly arrived, and I showed them around. The family friend, an older gentleman, was very appreciative, admiring everything I had done, complimenting me on my workmanship, and so on. And then, at the end of the visit, he pitched me a new price, substantially lower than the offer my colleague had previously made. I was caught off guard. Having refused the new price, I felt I had to respond to his questions, starting with what was the lowest price I would accept? He came back with requests to throw in this and that if they agreed to a higher price, and so on. We eventually agreed a deal – which actually was not such a bad deal from my point of view – but I was left feeling bruised.

Looking back, I have to admire the technique. All the praise, all the efforts to make me feel good first, worked a treat, and there was nothing in the negotiation itself that I could criticise. He did a good job for my colleague. So why did I feel bruised?

The one thing that was missing in the exchange was creating an honest expectation. I had been led to believe that the friend was there to give a second opinion. It was my colleague’s first house purchase, just as it had been mine, so understandably he wanted someone else to endorse his judgement. I had not expected that the friend was there to negotiate on his behalf – after all, an offer had already been made. Perhaps I was a bit naïve, but I was caught unprepared; the negotiation had high financial and emotional value for me, and I had no experience of handling something like that. I felt that I was backed into a corner, and that personal trust had been breached.

So what is the lesson? Don’t just play fair – make sure everyone knows what game you are going to be playing beforehand, especially if personal relationships are involved. Trust is too important, and too hard to rebuild, to risk losing.

English: Terraced house façades, Montague Street See also 1608624 (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

I’ll never forget my first serious experience of negotiation.

I was selling my first house, a small, terraced house in a cheap part of the city. I loved it, because it was the first house I had owned, and because I had put a lot of work – and a lot of myself – into it. I had decorated every room; I had refitted the kitchen; I had installed central heating to replace electric storage heaters. I was moving to a new area, where I knew housing was going to be a lot more expensive.

I had received an offer to buy my house from a junior colleague at work. Obviously that made things slightly awkward to start with. But I was unprepared for what happened when he asked if he could visit again, with a family friend.

They duly arrived, and I showed them around. The family friend, an older gentleman, was very appreciative, admiring everything I had done, complimenting me on my workmanship, and so on. And then, at the end of the visit, he pitched me a new price, substantially lower than the offer my colleague had previously made. I was caught off guard. Having refused the new price, I felt I had to respond to his questions, starting with what was the lowest price I would accept? He came back with requests to throw in this and that if they agreed to a higher price, and so on. We eventually agreed a deal – which actually was not such a bad deal from my point of view – but I was left feeling bruised.

Looking back, I have to admire the technique. All the praise, all the efforts to make me feel good first, worked a treat, and there was nothing in the negotiation itself that I could criticise. He did a good job for my colleague. So why did I feel bruised?

The one thing that was missing in the exchange was creating an honest expectation. I had been led to believe that the friend was there to give a second opinion. It was my colleague’s first house purchase, just as it had been mine, so understandably he wanted someone else to endorse his judgement. I had not expected that the friend was there to negotiate on his behalf – after all, an offer had already been made. Perhaps I was a bit naïve, but I was caught unprepared; the negotiation had high financial and emotional value for me, and I had no experience of handling something like that. I felt that I was backed into a corner, and that personal trust had been breached.

So what is the lesson? Don’t just play fair – make sure everyone knows what game you are going to be playing beforehand, especially if personal relationships are involved. Trust is too important, and too hard to rebuild, to risk losing.

English: Terraced house façades, Montague Street See also 1608624 (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

I’ll never forget my first serious experience of negotiation.

I was selling my first house, a small, terraced house in a cheap part of the city. I loved it, because it was the first house I had owned, and because I had put a lot of work – and a lot of myself – into it. I had decorated every room; I had refitted the kitchen; I had installed central heating to replace electric storage heaters. I was moving to a new area, where I knew housing was going to be a lot more expensive.

I had received an offer to buy my house from a junior colleague at work. Obviously that made things slightly awkward to start with. But I was unprepared for what happened when he asked if he could visit again, with a family friend.

They duly arrived, and I showed them around. The family friend, an older gentleman, was very appreciative, admiring everything I had done, complimenting me on my workmanship, and so on. And then, at the end of the visit, he pitched me a new price, substantially lower than the offer my colleague had previously made. I was caught off guard. Having refused the new price, I felt I had to respond to his questions, starting with what was the lowest price I would accept? He came back with requests to throw in this and that if they agreed to a higher price, and so on. We eventually agreed a deal – which actually was not such a bad deal from my point of view – but I was left feeling bruised.

Looking back, I have to admire the technique. All the praise, all the efforts to make me feel good first, worked a treat, and there was nothing in the negotiation itself that I could criticise. He did a good job for my colleague. So why did I feel bruised?

The one thing that was missing in the exchange was creating an honest expectation. I had been led to believe that the friend was there to give a second opinion. It was my colleague’s first house purchase, just as it had been mine, so understandably he wanted someone else to endorse his judgement. I had not expected that the friend was there to negotiate on his behalf – after all, an offer had already been made. Perhaps I was a bit naïve, but I was caught unprepared; the negotiation had high financial and emotional value for me, and I had no experience of handling something like that. I felt that I was backed into a corner, and that personal trust had been breached.

So what is the lesson? Don’t just play fair – make sure everyone knows what game you are going to be playing beforehand, especially if personal relationships are involved. Trust is too important, and too hard to rebuild, to risk losing.

English: Terraced house façades, Montague Street See also 1608624 (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

I’ll never forget my first serious experience of negotiation.

I was selling my first house, a small, terraced house in a cheap part of the city. I loved it, because it was the first house I had owned, and because I had put a lot of work – and a lot of myself – into it. I had decorated every room; I had refitted the kitchen; I had installed central heating to replace electric storage heaters. I was moving to a new area, where I knew housing was going to be a lot more expensive.

I had received an offer to buy my house from a junior colleague at work. Obviously that made things slightly awkward to start with. But I was unprepared for what happened when he asked if he could visit again, with a family friend.

They duly arrived, and I showed them around. The family friend, an older gentleman, was very appreciative, admiring everything I had done, complimenting me on my workmanship, and so on. And then, at the end of the visit, he pitched me a new price, substantially lower than the offer my colleague had previously made. I was caught off guard. Having refused the new price, I felt I had to respond to his questions, starting with what was the lowest price I would accept? He came back with requests to throw in this and that if they agreed to a higher price, and so on. We eventually agreed a deal – which actually was not such a bad deal from my point of view – but I was left feeling bruised.

Looking back, I have to admire the technique. All the praise, all the efforts to make me feel good first, worked a treat, and there was nothing in the negotiation itself that I could criticise. He did a good job for my colleague. So why did I feel bruised?

The one thing that was missing in the exchange was creating an honest expectation. I had been led to believe that the friend was there to give a second opinion. It was my colleague’s first house purchase, just as it had been mine, so understandably he wanted someone else to endorse his judgement. I had not expected that the friend was there to negotiate on his behalf – after all, an offer had already been made. Perhaps I was a bit naïve, but I was caught unprepared; the negotiation had high financial and emotional value for me, and I had no experience of handling something like that. I felt that I was backed into a corner, and that personal trust had been breached.

So what is the lesson? Don’t just play fair – make sure everyone knows what game you are going to be playing beforehand, especially if personal relationships are involved. Trust is too important, and too hard to rebuild, to risk losing.

[caption id="" align="alignright" width="300"] Wing mirror VW Fox (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

Last week I had to drive my daughter to France to start a year of study at a French University. As you can imagine, the (small) car was packed to the roof with all the things she needed, or at least believed she needed, and which could not possibly get there any other way. Result – the rear view mirror only gave me a view of some pillows, which was not a lot of help. However, I very quickly adjusted to relying entirely on the wing mirrors, and felt reasonably safe even though I was driving on the ‘wrong’ side of the road.

The strange thing was that on the return journey, having unloaded in Nantes, I continued in the same way. It was only chance that I glanced in the direction of the main mirror, and realised that it was (of course) no longer obstructed. Information inertia!

Wing mirror VW Fox (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

Last week I had to drive my daughter to France to start a year of study at a French University. As you can imagine, the (small) car was packed to the roof with all the things she needed, or at least believed she needed, and which could not possibly get there any other way. Result – the rear view mirror only gave me a view of some pillows, which was not a lot of help. However, I very quickly adjusted to relying entirely on the wing mirrors, and felt reasonably safe even though I was driving on the ‘wrong’ side of the road.

The strange thing was that on the return journey, having unloaded in Nantes, I continued in the same way. It was only chance that I glanced in the direction of the main mirror, and realised that it was (of course) no longer obstructed. Information inertia!

Wing mirror VW Fox (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

Last week I had to drive my daughter to France to start a year of study at a French University. As you can imagine, the (small) car was packed to the roof with all the things she needed, or at least believed she needed, and which could not possibly get there any other way. Result – the rear view mirror only gave me a view of some pillows, which was not a lot of help. However, I very quickly adjusted to relying entirely on the wing mirrors, and felt reasonably safe even though I was driving on the ‘wrong’ side of the road.

The strange thing was that on the return journey, having unloaded in Nantes, I continued in the same way. It was only chance that I glanced in the direction of the main mirror, and realised that it was (of course) no longer obstructed. Information inertia!

Wing mirror VW Fox (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

Last week I had to drive my daughter to France to start a year of study at a French University. As you can imagine, the (small) car was packed to the roof with all the things she needed, or at least believed she needed, and which could not possibly get there any other way. Result – the rear view mirror only gave me a view of some pillows, which was not a lot of help. However, I very quickly adjusted to relying entirely on the wing mirrors, and felt reasonably safe even though I was driving on the ‘wrong’ side of the road.

The strange thing was that on the return journey, having unloaded in Nantes, I continued in the same way. It was only chance that I glanced in the direction of the main mirror, and realised that it was (of course) no longer obstructed. Information inertia!

Information inertia

Businesses need to rely more on looking forwards than looking back (as do drivers!) but the lesson for me was how easy it is to continue to rely on the kind of information which we have become used to, even when better information becomes available – and even when you really should know it is there. Of course it is comforting to have the same monthly report format that you have always had. You know exactly what information will be there, and where to find it. There is always a cost-benefit question around extra information, and it certainly needs to earn its keep. Nonetheless, it is a good idea to ask yourselves regularly whether there is any new information which should be added. A few years ago I needed to hire an assistant. I’d fixed an interview, and everything was organised. It was five minutes before the time the candidate was due, and I was just collecting my papers and my thoughts. At that moment, the din of the fire alarm started up.

There is – of course – nothing that you can do. Down the concrete back stairs, and out round the back of the building to the assembly point, into the London drizzle without a coat, while I imagined my interviewee arriving at the front. I had left all my papers on my desk in the dry, and had no other record of his contact details, so I had no way to suggest an alternative plan.

A little while later, my mobile rang. Having arrived and been barred from entry, he had managed to track down my mobile number himself, and we were able to arrange to carry on with the interview while we dried out in a local coffee shop. Needless to say, his resourcefulness impressed me and he got the job. Despite the unhelpful circumstances of the interview, he was one of my best hires ever.

Life has a habit of not going the way we plan it. Unexpected circumstances can often be turned to our advantage though, if we grasp them rather than trying to stick to the plan, and often the results are better than you could possibly have expected.

A few years ago I needed to hire an assistant. I’d fixed an interview, and everything was organised. It was five minutes before the time the candidate was due, and I was just collecting my papers and my thoughts. At that moment, the din of the fire alarm started up.

There is – of course – nothing that you can do. Down the concrete back stairs, and out round the back of the building to the assembly point, into the London drizzle without a coat, while I imagined my interviewee arriving at the front. I had left all my papers on my desk in the dry, and had no other record of his contact details, so I had no way to suggest an alternative plan.

A little while later, my mobile rang. Having arrived and been barred from entry, he had managed to track down my mobile number himself, and we were able to arrange to carry on with the interview while we dried out in a local coffee shop. Needless to say, his resourcefulness impressed me and he got the job. Despite the unhelpful circumstances of the interview, he was one of my best hires ever.

Life has a habit of not going the way we plan it. Unexpected circumstances can often be turned to our advantage though, if we grasp them rather than trying to stick to the plan, and often the results are better than you could possibly have expected.

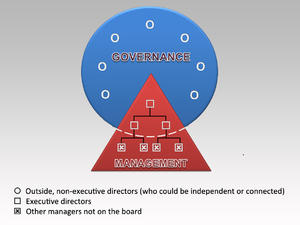

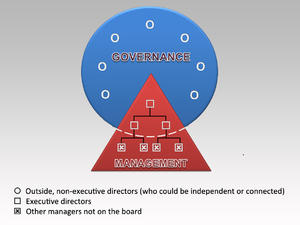

[caption id="" align="alignright" width="300"] English: Corporate Governance (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

All organisations have to find an appropriate balance between central control and local freedom to act. Governance provides the framework and checks and balances within which this is established and managed. It ensures that the process by which decisions are made is appropriately managed. It allows them to be seen to have been taken in the best interests of the shareholders, taking account of all the demands on the organisation, the risks, and the information available at the time.

English: Corporate Governance (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

All organisations have to find an appropriate balance between central control and local freedom to act. Governance provides the framework and checks and balances within which this is established and managed. It ensures that the process by which decisions are made is appropriately managed. It allows them to be seen to have been taken in the best interests of the shareholders, taking account of all the demands on the organisation, the risks, and the information available at the time.

English: Corporate Governance (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

All organisations have to find an appropriate balance between central control and local freedom to act. Governance provides the framework and checks and balances within which this is established and managed. It ensures that the process by which decisions are made is appropriately managed. It allows them to be seen to have been taken in the best interests of the shareholders, taking account of all the demands on the organisation, the risks, and the information available at the time.

English: Corporate Governance (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

All organisations have to find an appropriate balance between central control and local freedom to act. Governance provides the framework and checks and balances within which this is established and managed. It ensures that the process by which decisions are made is appropriately managed. It allows them to be seen to have been taken in the best interests of the shareholders, taking account of all the demands on the organisation, the risks, and the information available at the time.

Review your governance

If several of the following statements are true of your organisation, it may well be a good idea to review your governance arrangements.- The governance structure (meetings and delegations) does not constitute a simple hierarchy underneath the Board, with clear parent-child relationships and information cascaded up and down the hierarchy

- The governance structure is not clearly documented (e.g. including a consistent set of Terms of Reference), communicated and understood

- People do not have clear written instructions as to the limits of the authority that they have been given, or these are ignored

- Committees are allowed to approve their own Terms of Reference and/or memberships

- Governance meetings happen irregularly, or with papers which are poor quality or issued late

- Senior staff are allowed to ignore the rules which apply to others

- Decisions are often taken late because of papers missing submission dates, inadequate information, wrong attendance, submission to the wrong meeting, unexpected need for escalation, etc

- There is a feeling that the governance process is too bureaucratic

The other night I was meeting a friend for dinner in town. You know how sometimes when you get down to the tube platform it feels wrong? It felt wrong. Too many people, milling about with resigned looks, not purposefully waiting. Then the public announcement: “the Victoria line is suspended from Victoria to Walthamstow Central. There is a shuttle service operating between Brixton and Victoria.”

No train. No boards telling you when the next train is coming either. I have a choice: I can take the chance of waiting, hoping that if a train does come soon I might still be on time – but it might be ages; or I can go out and catch a bus – I will definitely be a bit late, but I know it will definitely come?

The other night I was meeting a friend for dinner in town. You know how sometimes when you get down to the tube platform it feels wrong? It felt wrong. Too many people, milling about with resigned looks, not purposefully waiting. Then the public announcement: “the Victoria line is suspended from Victoria to Walthamstow Central. There is a shuttle service operating between Brixton and Victoria.”

No train. No boards telling you when the next train is coming either. I have a choice: I can take the chance of waiting, hoping that if a train does come soon I might still be on time – but it might be ages; or I can go out and catch a bus – I will definitely be a bit late, but I know it will definitely come?

How do we deal with risk?

It’s a nice example of how we human beings deal with risk. I don’t know about you, but my thought process goes something like this. First I will take the higher risk option – perhaps partly because it is where I am. As I wait, and nothing happens, I weigh up how late I am going to be if I catch the bus. At some point (if I am still waiting) I decide to cut my losses – either way I’m going to be late, so I opt for the more certain course and catch the bus. This time, I waited 10 minutes before changing to Plan B, and was 20 minutes late. If I had changed immediately I would only have been 10 minutes late. It’s not very rational – the sensible thing surely is to take the low risk option as early as possible, minimising the lateness, rather than just hoping that Plan A will avoid us being late at all, and then finishing up being later than we needed to be. But it seems to be human nature to take the optimistic view like this. Usually when we have to deal with risk there is some kind of pain threshold we have to exceed before we are willing to consider an alternative course, even though the sensible point to do so may have been much earlier. I don’t know how much unnecessary pain we suffer as a result, but I suspect it is significant! Do you need help identifying the change options you have to deal with risk? Please get in touch. I’m on my way to a Board meeting. My job as a Board member is to turn up about once a month for a meeting lasting normally no more than a couple of hours to take the most important decisions the company needs – decisions which are often about complex areas, fraught with operational, commercial, legal and possibly political implications, and often with ambitious managers or other vested interests arguing strongly (but not necessarily objectively) for their preferred outcome. Few of the decisions are black and white, but most carry significant risk for the organisation. Good outcomes rely on informing Board members effectively.

This is a well-managed organisation, so I have received the papers for the meeting a week in advance, but I have had no chance to seek clarification of anything which is unclear, or to ask for further information. In many organisations, the papers may arrive late, or they may have been poorly written so that the story they tell is incomplete or hard to understand (despite often being very detailed), or both. The Board meeting, with a packed agenda and a timetable to keep to, is my only chance to fill the gaps.

I have years of experience to draw on, but experience can only take me so far. Will I miss an assumption that ought to be challenged, or a risk arising from something I am not familiar with? If that happens, we may make a poor decision, and I will share the responsibility. In some cases – for instance a safety issue - that might have serious consequences for other people. It’s not a happy thought.

I’m on my way to a Board meeting. My job as a Board member is to turn up about once a month for a meeting lasting normally no more than a couple of hours to take the most important decisions the company needs – decisions which are often about complex areas, fraught with operational, commercial, legal and possibly political implications, and often with ambitious managers or other vested interests arguing strongly (but not necessarily objectively) for their preferred outcome. Few of the decisions are black and white, but most carry significant risk for the organisation. Good outcomes rely on informing Board members effectively.

This is a well-managed organisation, so I have received the papers for the meeting a week in advance, but I have had no chance to seek clarification of anything which is unclear, or to ask for further information. In many organisations, the papers may arrive late, or they may have been poorly written so that the story they tell is incomplete or hard to understand (despite often being very detailed), or both. The Board meeting, with a packed agenda and a timetable to keep to, is my only chance to fill the gaps.

I have years of experience to draw on, but experience can only take me so far. Will I miss an assumption that ought to be challenged, or a risk arising from something I am not familiar with? If that happens, we may make a poor decision, and I will share the responsibility. In some cases – for instance a safety issue - that might have serious consequences for other people. It’s not a happy thought.