For the last few weeks I have been posting about general principles of governance. Let’s turn to a practical example: How do those principles apply to programme management? There is of course no one ‘right way’ – it depends on the context. However, there definitely are ‘wrong’ ways, and they are all too common!

Most programmes have a Programme Director, and most have a Programme Board. What are their roles, and how should they be related?

Programme Board

The Programme Board should be a fundamental part of the governance structure. There would be no point in it being there unless it makes decisions. To do that, it must be given authority by some other body, which must itself have the authority to do that. Programme Boards typically have as part of their role resolving cross-functional issues for the programme. Consequently, they will normally be set up to report to a committee within the governance structure which itself has cross-functional representation. If the Programme Board is unable to resolve an issue which comes to it, normally its parent will need to. If a Programme Board were to report to an individual, it would be hard to see how that individual could more effectively resolve any cross-functional issue that had to be escalated.Programme Director

The Programme Director’s role will vary in detail between programmes, but fundamentally he or she is the person accountable for making sure that the expected outcomes of the programme are delivered within the constraints agreed. That leads us to two further points. First, if they are accountable, who will hold them to account? That is another part of the role of the Programme Board. The Programme Director will present progress reports, papers for decision, etc to the Programme Board, to enable them to do that. A corollary is that the Programme Director should be appointed, or at least confirmed, by the Programme Board, which will also delegate authority. If things are not going well, it is the Programme Board that must decide whether a change of Programme Director is required. Second, what is the nature of the relationship between the Programme Director and the Programme Board? Essentially it is like a contract. The Programme Board is the customer for the programme, approving the programme requirements. The Programme Director represents the delivery team - the contractor, if you will - and needs to make sure that sufficient time and resources are allocated to the programme to deliver the requirements. Clearly making the two join up may require negotiation. If there are subsequent changes to requirements, agreeing how to accommodate these – extra resource, recognising more risk, delay or reduced quality – will require a further negotiation. Remember, accountability and authority need to go together. Just as with the CEO and a company Board, it is clear that the Programme Director has a fundamentally different role to that of the Programme Board, and to blur these distinctions will introduce conflicts of interest. Of course the Programme Director will normally attend Programme Boards, although that does not mean that they have to be a member (and the different roles are clearer if they are not). Either way, though, they should never be the Chair: they would have a clear conflict of interest. At best they would be tempted to steer the agenda away from certain issues, and it would become impossible for the Board to be effective in holding them to account. No-one should be asked to mark their own homework! It follows that the members of the Programme Board should not normally be junior to the Programme Director, and certainly should not be his or her direct reports. Of course there is a place for meetings of the Programme Team – but those are progress meetings, not Programme Boards. Do your Programme Boards follow these rules?What is governance for?

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if whenever you asked someone to do something, they just did it? And of course, on the other hand, that they didn’t do things which they had not been asked to do? Oh for perfect control! But wait a moment. Midas asked that everything he touched should turn to gold – and look where that got him. Perhaps we had better be careful what we wish for. How often have you said “No, that’s not what I meant!”? Or “I’d have thought it was obvious that that needed doing!”? Let’s face it, most of us are not that great at giving really good instructions about what we need, and we certainly don’t have time to include every detail. At the same time, the people we ask are intelligent and creative. We get better outcomes, and they enjoy the work more and so are more motivated, when we expect them to use those abilities to interpret our needs sensibly and come up with the best solutions, even when we didn’t think to ask. In summary, then, we have specific outcomes we require, but it is neither practical nor desirable for us to be completely prescriptive about how they should be delivered. Governance provides a framework within which the desires for control of outcomes and for flexibility over means can be reconciled with the minimum of effort. Such a framework is fundamentally about good behaviours. Most of us want to behave well, but doing things the way we know would be best often takes more time and effort (at least in the short term), and time is one thing that is always in short supply. Formal governance arrangements help to stop us taking the short cuts which may be unhelpful in the long run. They ensure that we communicate what we are doing – so that changes can be made if required – and may force us to plan a bit further ahead. Being able to see good governance in place reassures stakeholders that the organisation is behaving transparently. It gives Government bodies and Regulators confidence that the organisation is complying with legislation and other requirements. And it allows Boards and managers to delegate authority while retaining sufficient control. Good governance means that we not only behave honestly and competently, but are seen to be doing so, which builds trust. In short, it is the rock on which a well-managed organisation is built. What good governance is NOT about is bureaucracy, box-ticking and delays. It requires finding balances – between control and practical delivery; between the risks of delegation and the cost of control; between wide ownership of decisions and strong accountability for them; between a simple structure and efficient decision-making; between minimum overhead and an effective audit trail – which provide the optimum basis for success. Every organisation has different arrangements because the optimum trade-offs depend on the context. This is the first of a series of articles will set out the main issues to be considered in designing an internal governance system and the principles which should underlie it.

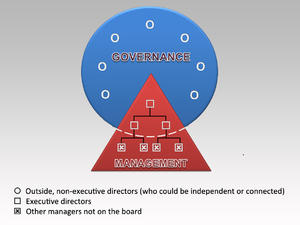

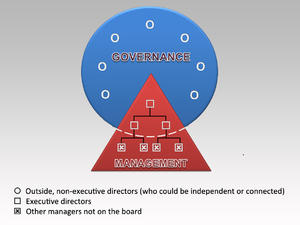

[caption id="" align="alignright" width="300"] English: Corporate Governance (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

All organisations have to find an appropriate balance between central control and local freedom to act. Governance provides the framework and checks and balances within which this is established and managed. It ensures that the process by which decisions are made is appropriately managed. It allows them to be seen to have been taken in the best interests of the shareholders, taking account of all the demands on the organisation, the risks, and the information available at the time.

English: Corporate Governance (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

All organisations have to find an appropriate balance between central control and local freedom to act. Governance provides the framework and checks and balances within which this is established and managed. It ensures that the process by which decisions are made is appropriately managed. It allows them to be seen to have been taken in the best interests of the shareholders, taking account of all the demands on the organisation, the risks, and the information available at the time.

English: Corporate Governance (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

All organisations have to find an appropriate balance between central control and local freedom to act. Governance provides the framework and checks and balances within which this is established and managed. It ensures that the process by which decisions are made is appropriately managed. It allows them to be seen to have been taken in the best interests of the shareholders, taking account of all the demands on the organisation, the risks, and the information available at the time.

English: Corporate Governance (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

All organisations have to find an appropriate balance between central control and local freedom to act. Governance provides the framework and checks and balances within which this is established and managed. It ensures that the process by which decisions are made is appropriately managed. It allows them to be seen to have been taken in the best interests of the shareholders, taking account of all the demands on the organisation, the risks, and the information available at the time.

Review your governance

If several of the following statements are true of your organisation, it may well be a good idea to review your governance arrangements.- The governance structure (meetings and delegations) does not constitute a simple hierarchy underneath the Board, with clear parent-child relationships and information cascaded up and down the hierarchy

- The governance structure is not clearly documented (e.g. including a consistent set of Terms of Reference), communicated and understood

- People do not have clear written instructions as to the limits of the authority that they have been given, or these are ignored

- Committees are allowed to approve their own Terms of Reference and/or memberships

- Governance meetings happen irregularly, or with papers which are poor quality or issued late

- Senior staff are allowed to ignore the rules which apply to others

- Decisions are often taken late because of papers missing submission dates, inadequate information, wrong attendance, submission to the wrong meeting, unexpected need for escalation, etc

- There is a feeling that the governance process is too bureaucratic