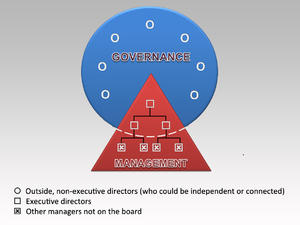

[caption id="" align="alignright" width="300"] English: Corporate Governance (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

All organisations have to find an appropriate balance between central control and local freedom to act. Governance provides the framework and checks and balances within which this is established and managed. It ensures that the process by which decisions are made is appropriately managed. It allows them to be seen to have been taken in the best interests of the shareholders, taking account of all the demands on the organisation, the risks, and the information available at the time.

English: Corporate Governance (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

All organisations have to find an appropriate balance between central control and local freedom to act. Governance provides the framework and checks and balances within which this is established and managed. It ensures that the process by which decisions are made is appropriately managed. It allows them to be seen to have been taken in the best interests of the shareholders, taking account of all the demands on the organisation, the risks, and the information available at the time.

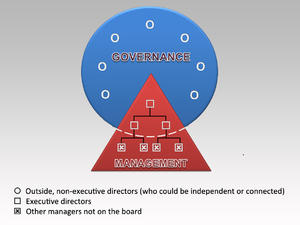

English: Corporate Governance (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

All organisations have to find an appropriate balance between central control and local freedom to act. Governance provides the framework and checks and balances within which this is established and managed. It ensures that the process by which decisions are made is appropriately managed. It allows them to be seen to have been taken in the best interests of the shareholders, taking account of all the demands on the organisation, the risks, and the information available at the time.

English: Corporate Governance (Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

All organisations have to find an appropriate balance between central control and local freedom to act. Governance provides the framework and checks and balances within which this is established and managed. It ensures that the process by which decisions are made is appropriately managed. It allows them to be seen to have been taken in the best interests of the shareholders, taking account of all the demands on the organisation, the risks, and the information available at the time.

Review your governance

If several of the following statements are true of your organisation, it may well be a good idea to review your governance arrangements.- The governance structure (meetings and delegations) does not constitute a simple hierarchy underneath the Board, with clear parent-child relationships and information cascaded up and down the hierarchy

- The governance structure is not clearly documented (e.g. including a consistent set of Terms of Reference), communicated and understood

- People do not have clear written instructions as to the limits of the authority that they have been given, or these are ignored

- Committees are allowed to approve their own Terms of Reference and/or memberships

- Governance meetings happen irregularly, or with papers which are poor quality or issued late

- Senior staff are allowed to ignore the rules which apply to others

- Decisions are often taken late because of papers missing submission dates, inadequate information, wrong attendance, submission to the wrong meeting, unexpected need for escalation, etc

- There is a feeling that the governance process is too bureaucratic

I’m on my way to a Board meeting. My job as a Board member is to turn up about once a month for a meeting lasting normally no more than a couple of hours to take the most important decisions the company needs – decisions which are often about complex areas, fraught with operational, commercial, legal and possibly political implications, and often with ambitious managers or other vested interests arguing strongly (but not necessarily objectively) for their preferred outcome. Few of the decisions are black and white, but most carry significant risk for the organisation. Good outcomes rely on informing Board members effectively.

This is a well-managed organisation, so I have received the papers for the meeting a week in advance, but I have had no chance to seek clarification of anything which is unclear, or to ask for further information. In many organisations, the papers may arrive late, or they may have been poorly written so that the story they tell is incomplete or hard to understand (despite often being very detailed), or both. The Board meeting, with a packed agenda and a timetable to keep to, is my only chance to fill the gaps.

I have years of experience to draw on, but experience can only take me so far. Will I miss an assumption that ought to be challenged, or a risk arising from something I am not familiar with? If that happens, we may make a poor decision, and I will share the responsibility. In some cases – for instance a safety issue - that might have serious consequences for other people. It’s not a happy thought.

I’m on my way to a Board meeting. My job as a Board member is to turn up about once a month for a meeting lasting normally no more than a couple of hours to take the most important decisions the company needs – decisions which are often about complex areas, fraught with operational, commercial, legal and possibly political implications, and often with ambitious managers or other vested interests arguing strongly (but not necessarily objectively) for their preferred outcome. Few of the decisions are black and white, but most carry significant risk for the organisation. Good outcomes rely on informing Board members effectively.

This is a well-managed organisation, so I have received the papers for the meeting a week in advance, but I have had no chance to seek clarification of anything which is unclear, or to ask for further information. In many organisations, the papers may arrive late, or they may have been poorly written so that the story they tell is incomplete or hard to understand (despite often being very detailed), or both. The Board meeting, with a packed agenda and a timetable to keep to, is my only chance to fill the gaps.

I have years of experience to draw on, but experience can only take me so far. Will I miss an assumption that ought to be challenged, or a risk arising from something I am not familiar with? If that happens, we may make a poor decision, and I will share the responsibility. In some cases – for instance a safety issue - that might have serious consequences for other people. It’s not a happy thought.

Informing Board members

In order for a Board (or any other body) to make good decisions, it has to be in possession of appropriate information. These are some of the rules I have followed when I have set up arrangements to promote effective governance.Good papers

Good papers tell the story completely and logically, but concisely. They do not assume that the reader knows the background. They build the picture without jumping around, and make clear and well-argued recommendations. They do not confuse with unnecessary detail, but nor do they overlook important aspects. As Einstein said, “If you can't explain it simply, you don't understand it well enough." Provide rules on length, apply (pragmatic) quality control to the papers received, and refuse to include papers if they do not meet minimum requirements (obviously it helps to be able to give advice on how to make them acceptable). You must of course choose a reviewer whose judgements will be respected. This may well result in some painful discussions, but people only learn the hard way.Timely distribution

If members do not have time to read the papers properly, it does not matter how good they are. If I am a busy Board member, I may need to reserve time in my diary for meeting preparation, and this is a problem if I cannot rely on papers arriving on time. Set submission deadlines which allow for timely and predictable distribution, and enforce them. Again, be prepared for some painful discussions until people learn.Informal channels

Concise papers and busy Board meetings are never going to allow for deep understanding of context. To overcome this, I have organised informal sessions immediately preceding Board meetings, over a sandwich lunch if the timing requires. Allocate a couple of hours for just two or three topics; bring in the subject experts, but spend most of the time on discussion. Not all Board members will be able to attend every session, but in my experience not only have they found them hugely valuable in building their wider knowledge of the business, but the opportunity to meet more junior staff has been appreciated all round. There are many other ways that informal channels could be set up. Different things will work in different organisations. Key to all of them is building trust: informing Board members properly means allowing them to see things “warts and all”, and trusting a wider group of staff to talk to them.Organisation

To do all of these things effectively, you need to have someone (or in larger organisations a small secretariat team) whose primary objective is to deliver them. This is not glamorous stuff, however important, and it easily gets put to the bottom of the pile without clear leadership. Finally, remember that nothing will happen unless the importance of this is understood at the very top. If the CEO does not set an example by sticking to time and quality rules, no one else will. A few years ago, I spent a fascinating week travelling around Europe. I was trying to put together a consortium to bid for funding from an EU industrial research programme. I was selling a vision. It was one of those “if its Wednesday I must be in France” trips, where after a couple of days my brain’s language processor gets so confused it just gives up attempting anything except English. Fortunately (but as usual), my hosts all put me to shame by speaking excellent English to me.

This trip taught me a very important lesson about selling a vision which I have used many times since. No organisation wants to be the first to commit to partnering when all they have is an outline description of the objectives of the partnership. They feel they need to know who else will be a part of it, and what the content of the programme will look like. Without this, they don’t even really want to share their ideas of what they might contribute or what benefits they might receive. On the other hand, until they do share their ideas it is impossible to put together a realistic programme. So where do you begin?

I describe what I did as “Castles in the air”. Think of the project as a fairy-tale castle floating above the ground. You have to be able to describe in some detail what this castle looks like from a distance. Of course, no-one can actually get to it to look inside, so much of the detail does not need to be filled in, but the description has to be convincing enough that everyone believes it is a real castle, not an illusion. In particular, they must never think that there is nothing holding it up!

A few years ago, I spent a fascinating week travelling around Europe. I was trying to put together a consortium to bid for funding from an EU industrial research programme. I was selling a vision. It was one of those “if its Wednesday I must be in France” trips, where after a couple of days my brain’s language processor gets so confused it just gives up attempting anything except English. Fortunately (but as usual), my hosts all put me to shame by speaking excellent English to me.

This trip taught me a very important lesson about selling a vision which I have used many times since. No organisation wants to be the first to commit to partnering when all they have is an outline description of the objectives of the partnership. They feel they need to know who else will be a part of it, and what the content of the programme will look like. Without this, they don’t even really want to share their ideas of what they might contribute or what benefits they might receive. On the other hand, until they do share their ideas it is impossible to put together a realistic programme. So where do you begin?

I describe what I did as “Castles in the air”. Think of the project as a fairy-tale castle floating above the ground. You have to be able to describe in some detail what this castle looks like from a distance. Of course, no-one can actually get to it to look inside, so much of the detail does not need to be filled in, but the description has to be convincing enough that everyone believes it is a real castle, not an illusion. In particular, they must never think that there is nothing holding it up!

Selling a vision

Putting that into project terms, there has to be a clear vision of what the project could do, broadly who may be involved and how they will benefit, even though none of it is agreed, and you have to feel and sound confident about it, just in order to get people talking about how they might contribute. Once you can get possible contributors to engage, they will help you fill in the detail, adapt the vision and underpin it with the foundations, until the whole project is solid enough to stand up by itself. The same principles apply to any situation where you need to influence many different people to win their support for the same idea. Unless you can describe your “castle in the air” with confidence, as though it were real and solid, it will be very difficult to get a hearing at all. The more people listen and contribute, even if they are not yet fully convinced, the easier it gets to win over others. Years ago, I was managing the sale of a business division. The business was based on carrying out a highly-specialised technical test on clients’ products, and each time a test was carried out, it made a loud bang. This would have been of no concern if it had not been that they were carried out in a large workshop also used for other activities. However, checks had been made and the noise levels were within legal safety limits.

Just before signing the deal, we happened to mention to the purchaser that we had some tests scheduled for the next day, and he said he’d like to send someone round to check the sound levels. It was a beautiful summer’s day – until their measurements showed that the bangs were over the limit. What a toe-curling moment! Clearly, we had made the wrong assumptions.

In the end it was not as bad as it seemed: a sound-attenuating box solved the problem without making access too difficult, at quite modest cost and with only a few weeks’ delay. But the proving tests provided another surprise – the noise levels were legal again without the box. The reason – we now realised – was that the humidity of the air could affect its sound-attenuating properties.

Years ago, I was managing the sale of a business division. The business was based on carrying out a highly-specialised technical test on clients’ products, and each time a test was carried out, it made a loud bang. This would have been of no concern if it had not been that they were carried out in a large workshop also used for other activities. However, checks had been made and the noise levels were within legal safety limits.

Just before signing the deal, we happened to mention to the purchaser that we had some tests scheduled for the next day, and he said he’d like to send someone round to check the sound levels. It was a beautiful summer’s day – until their measurements showed that the bangs were over the limit. What a toe-curling moment! Clearly, we had made the wrong assumptions.

In the end it was not as bad as it seemed: a sound-attenuating box solved the problem without making access too difficult, at quite modest cost and with only a few weeks’ delay. But the proving tests provided another surprise – the noise levels were legal again without the box. The reason – we now realised – was that the humidity of the air could affect its sound-attenuating properties.

Avoiding wrong assumptions

Conclusion 1 – Make sure you know what factors can affect your assumptions. Wrong assumptions may lead to disaster. Conclusion 2 – Don’t rely on conclusion 1! If something is critical, don’t rely on a modest safety margin – do what you can to increase it early, in case there is something you have not anticipated. Have you ever noticed how the crowds waiting for commuter trains at Paddington (or doubtless most other big terminus stations) nearly all stay on the concourse until the platform is announced, even though each train usually runs from the same platform every day (so the regular commuters who are the majority all know which it is likely to be)? Consequence – a great crush as everyone rushes at the ticket barriers at once.

Have you ever noticed how the crowds waiting for commuter trains at Paddington (or doubtless most other big terminus stations) nearly all stay on the concourse until the platform is announced, even though each train usually runs from the same platform every day (so the regular commuters who are the majority all know which it is likely to be)? Consequence – a great crush as everyone rushes at the ticket barriers at once.

Beating the crowd

There are always a small number of people who don’t wait. They go calmly through the barrier with no queues, and get seats exactly where they want, beating the crowd instead of risking no seat at all. Maybe once in a blue moon the platform is different and they have to move – but it’s rare. It’s a great illustration of how conformist people (or at least we Brits) tend to be. I would guess less than 5% make the rational risk-reward trade-off and act accordingly, beating the crowd. 95% of us prefer to be part of the herd – but I wonder whether it is the people you would expect? Now there’s an interesting way to separate the sheep from the goats! Given those proportions, it is hardly surprising that very few people embrace change before they have to – even if they would stand to benefit from being early adopters. On the other hand, as change managers we have no need to wait until everything is ready before making announcements, unlike station staff. Early communication leads to more organised loading!

What happens when an organisation grows up? Many things, but it is not so different from a child growing up: it develops organisation maturity.

As a child grows up, it develops its own habits, values, behaviours. It makes friends. It learns how to do things it could not do before. And it learns how to blend and adapt all of those things to create a consistent whole – its personality. With that comes self-confidence.

So it is with an organisation. In a young organisation – even a large one, perhaps formed from a merger – processes and structures may have been patched together un-adapted from different inheritances. Initially, the mixture of values, relationships, and so on, is unlikely to be self-consistent. Although they may be individually very experienced, managers are not used to working together, and do not know how each other will react in different circumstances. Trust takes time to develop.

Even for an established organisation, a major disruptive change in its environment can cause the same difficulties. The new environment is unfamiliar and the managers of the organisation may have varying responses. Confidence and trust in each other’s judgement in the new situation need to be re-established. Perhaps new people join the team. Processes and systems may need to be changed, because the organisation and its strategy are no longer aligned.

Nobody expects a small, young organisation to behave like a major corporation. However, with scale comes expectation. If you look like a grown-up, people expect you to behave like a grown-up and to have grown-up relationships. Just as with a child who looks much older than it is, the incongruity can cause difficulty for everyone.

Organisational self-confidence – maturity if you will – matters. When an organisation knows at all levels that ‘this is the way we do things round here’, everyone in it can stand their ground with confidence if they need to, in the knowledge that all their colleagues would back them up. Where there is underlying inconsistency, people do not have that confidence. Then it can feel as if you are standing on your own, rather than backed by a team - the whole is not greater than the sum of the parts. So an organisation in this situation needs to grow up fast.

What does it take to do something about this?

First, recognise the nature of the problem. Fundamentally the challenge is about joining things up. That makes it multi-dimensional, multi-functional, crossing all the silos. That in itself means the response has to be driven or at least supported from the top. It also means that it is best done by someone with no vested interest in the outcome. And while it will require detailed analytical work to understand and correct specific problems, it will also need influencing and people skills to ensure that the solutions are accepted and embraced.

I have worked in a number of organisations which have faced challenges of this sort, and helped them to find their way through them. If you are facing similar challenges which you would like to discuss, please contact me at david@otteryconsulting.co.uk.