I was once asked in an interview about tough decisions I’ve made, and how I made them. I understand why it might be thought important in the selection process: it seems like a good question. Doesn’t it tell you something about the individual’s ability to cope in difficult situations? However, on reflection I’m less convinced!

Thinking back over a number of my roles, I realised (to my surprise) that most of the important decisions I have taken have not seemed tough at all. By ‘tough’ I mean difficult to make; they may still have been hard to implement. Conversely, tough decisions (on that definition) have often not been particularly important.

I was once asked in an interview about tough decisions I’ve made, and how I made them. I understand why it might be thought important in the selection process: it seems like a good question. Doesn’t it tell you something about the individual’s ability to cope in difficult situations? However, on reflection I’m less convinced!

Thinking back over a number of my roles, I realised (to my surprise) that most of the important decisions I have taken have not seemed tough at all. By ‘tough’ I mean difficult to make; they may still have been hard to implement. Conversely, tough decisions (on that definition) have often not been particularly important.

What makes tough decisions?

So what makes a decision tough? Often it is when there are two potentially conflicting drivers for the decision which can’t be measured against each other. Most commonly, it is when my rational, analytical side is pulling me one way – and my emotional, intuitive side is pulling another. Weighing up the pros and cons of different choices is relatively easy when it can be an analytical exercise, but that depends on comparing apples with apples. When two choices are evenly balanced on that basis, your choice will make little difference, so there is no point agonising about it. The problem comes when the rational comparison gives one answer, but intuitively you feel it is wrong. Comparing a rational conclusion with an emotional one is like comparing apples and roses – there is simply no basis for the comparison. When they are in conflict, you must decide (without recourse to analysis or feeling!) whether to back the rational conclusion or the intuitive one. A simple example is selecting candidates for roles. Sometimes a candidate appears to tick all the boxes convincingly, but intuition gives a different answer. On the rare occasions when I have over-ridden my intuition, it has usually turned out to be a mistake. Based on experience, then, I know that I should normally go with intuition, however hard that feels. We are all different though. Perhaps everyone has to find out from their mistakes how to make their own tough decisions. What we should not do is confuse how hard it is to make a decision with how important it is.

In the old days, efficiency (doing things right) ruled. You made money by having more efficient processes than competitors, so your margin was higher on the same price. Scale was rewarded, because it brought efficiency, encouraging huge companies and standardised products. Flexibility was your enemy.

Now, technology has changed everything. Just because it is possible, effectiveness (doing the right thing) will rule. The customer will always be right, whatever they want. Can you imagine people now accepting Henry Ford’s statement that people could have any colour they wanted, so long as it was black? Scale and efficiency is not the only thing that matters any more – in this new world, value comes from responsiveness. Success requires using connections, building a community with customers and suppliers, and being creative.

In the days when efficiency led, market domination was the objective, because that was what allowed you to hold onto your “most efficient producer” badge. In the new world, domination is not the only determinant of success. Your company needs to be like a lumberjack on a log flume – constantly moving to stay on top despite the logs rolling, and needing the agility that comes most easily to small companies to do so.

Use consultants and interims for ideas and flexibility

This model lends itself readily to the de-centralised organisation, using consultants, interims, and other forms of flexible working to provide the skills needed when they are needed. To do this well, the organisation needs to be networked and connected; old-style hierarchies, linear processes and so on inhibit the flexibility required. In this post-Brexit-vote world, where no-one quite knows where we are going or what it will mean, that flexibility to adapt rapidly as the shape of the future emerges will be even more important. Winning will depend on having a culture which embraces flexibility and adapts to change. Darwin had a phrase for it: survival of the fittest. The species that survived were the ones with most variability. Work flexibly; bring in and try out new ideas; find better ways to succeed. Voting to be dinosaurs can’t change the laws of nature.

It was only in the latter stages of the referendum campaign that the penny dropped for me. I realised that the reason that the campaign was so much about emotion and so little about facts and likely consequences was that, whatever its ostensible purpose, the referendum had come to be about who we are. My identity is what I believe it to be, and what those I identify with believe it to be. The outcome of a referendum does not, cannot, change that, even if it can lead to a change of status.

It would obviously be nonsense if, when you asked someone whether they would be best off staying married or getting divorced, they stated their gender as the answer. Politicians have allowed a question about relationship to be given an answer about identity. Apples and oranges. In so doing they have shot themselves – and at the same time the whole country – in the foot.

How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

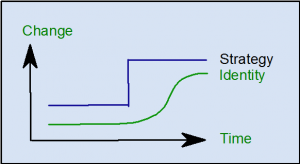

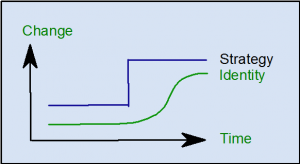

Identity and change

There is a profound lesson about change there. Identity is perhaps the ‘stickiest’ phenomenon in culture, because belonging is so fundamental to our sense of security. A change project is often perceived as changing in some way the identity of that to which we belong. However, peoples’ sense of identity changes much more slowly than the strategy. If we do not take steps to bridge the identity gap while people catch up, it is the relationship which is in for trouble. How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.

How do you do that? It is job of the vision you present to make people feel that they want to belong to the new future, and so to accept the discomfort of modifying their sense of identity. If people don’t buy into that vision, your chances of making the change successfully are low.

Whether or not it was deliverable, the ‘Leave’ campaign presented a simple vision of the future based on an identity which was clearly appealing to those disposed to believe it was. If ‘Remain’ presented a vision at all, it certainly did not make much attempt to sell an identity. It is reasonable to ask people about their identity, but we have representative democracy because you will still get the identity answer even if you ask them a relationship question.

If you want to bring about a successful change, start by making sure you have a believable vision which protects peoples’ identity and sense of belonging. Then campaign for that, even if it is not directly what the change is about.